The 200 crore vaccines conundrum: India's inoculation drive needs to relook at pace, price and access

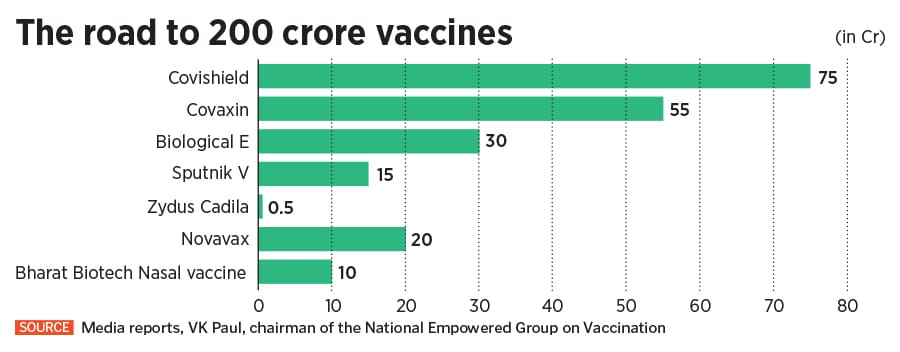

The Centre's ambitious plan of 200 crore doses by the year-end will require ramp-up of production, approval and manufacturing of new vaccines, and removing hesitancy and inequities in access. How realistic are the targets?

A healthcare worker injects a shepherd with Covishield vaccine during a vaccination drive at a forest area in south Kashmir's Pulwama district, June 7, 2021; Image: Danish Ismail / Reuters

A healthcare worker injects a shepherd with Covishield vaccine during a vaccination drive at a forest area in south Kashmir's Pulwama district, June 7, 2021; Image: Danish Ismail / Reuters

The world’s second worst Covid-19 affected country just can’t seem to figure out a viable vaccination programme. Despite that, it isn’t shying away from ambitious targets.

It’s been five months since India rolled out what was touted as the world’s largest vaccination programme. Yet, numerous flip-flops, ranging from policies on procurements to approvals for vaccines, continue to plague the inoculation drive even though the country remains the world's largest vaccine maker.

India has, so far, fully vaccinated about 4 percent of its population. Of its approximately 94 crore people above the age of 18, only 4 crore, or about 4.25 percent, have been fully vaccinated. As of June 9, a little over 20 percent have received at least one shot.

In contrast, over 42 percent of the US population have been fully vaccinated so far, while at least 63 percent in Israel have received one jab. Across Europe, over 30 percent in various countries have been vaccinated.

Meanwhile, India has now set an ambitious target of vaccinating all of its population above the age of 18 by December. By the looks of it, that’s going to be a Herculean task, especially considering the laggard pace so far.