Who benefits from the Farm Acts—farmers or private players?

With the Farm Bills receiving presidential assent and now becoming Acts, a fresh stir amongst farmers has broken out in the country. Stakeholders—both in favour of and against the bills—break down the positives and negatives

A farmer is detained by police during a protest against new farm laws, in Gandhinagar, India, September 28, 2020.

A farmer is detained by police during a protest against new farm laws, in Gandhinagar, India, September 28, 2020.

Image: Amit Dave/Reuters

Sharanjit Singh stood in the sweltering sun at PAP chowk in Jalandhar, Punjab, since 9 am on September 25. He was one of the 10,000-odd farmers and Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) members who had gathered for a dharna (strike) organised by farmers’ organisations and unions. "We’ll fight for our rights as long as we can,” says Singh.

Singh and his colleagues were protesting two contentious Rajya Sabha farm bills passed on September 20—Farmer’s Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, and the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020. Alongside, The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020 that was passed on September 22.

Singh and his colleagues were protesting two contentious Rajya Sabha farm bills passed on September 20—Farmer’s Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, and the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020. Alongside, The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill, 2020 that was passed on September 22.

The three bills were approved by the President on Monday, and the legislation will now come into force immediately. Protests by farmers and organisations have been dominating the streets across various cities ever since. In Karnataka, farmers and organisations are observing a bandh on Monday. The stir has intensified in Punjab and Haryana with Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD)—which recently ended its alliance with BJP over these farm bills—chief Sukhbir, Harsimarat leading the march in Lambi, Punjab.

In Delhi, a tractor was set on fire at India Gate as the protests turned violent. Opposition parties-led protests are being witnessed in Gujarat and Maharashtra.

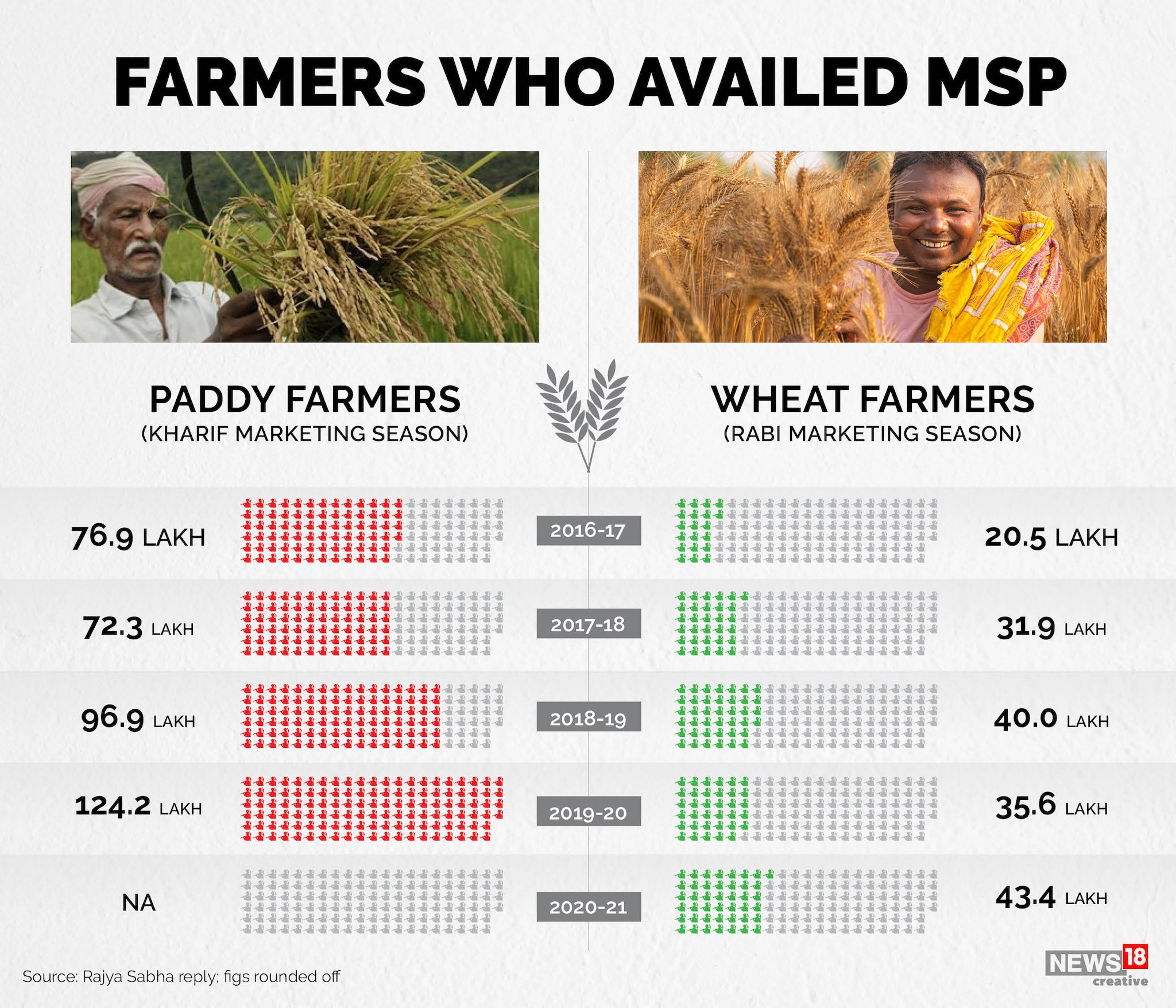

The protesting farmers have a few concerns—the annihilation of mandi system, including the role of arhityas (middlemen), and the eventual revocation of minimum support price (MSP), the fear of the proposed system of conciliation being misused against them, and the belief that private players will exploit them. Who will the new Act actually benefit?

MSPs and APMCs

Sharanjit Singh, the 38-year-old farmer, cultivates wheat and paddy on leased farms (in rotation) in the Nakodar area of Jalandhar district. “All we want is a provision in the bills that the MSP offered on our produce by the APMC mandis will not be abolished. Selling to corporations or private players directly should only be an option for us, not a mandate,” he explains.

The protesting farmers say that the three ordinances promulgated by the Centre on June 5 do not mention MSP or anything about government procurement, directly or indirectly.

However, progressive farmer Prakash Tiwari believes otherwise. An IIT graduate, Tiwari quit his corporate job with Ernst & Young in London to come back to his village, Gonda in Uttar Pradesh, to take up farming full-time. He says, "India's agriculture hasn't been in the best state, but I feel that the passing of these bills will revolutionise it. They were much needed."

According to Tiwari, with no restrictions on selling only to mandis, "farmers no longer have to travel miles, spend hefty amounts on transportation and then sell in the mandis for whatever price is demanded—since there is no scope for negotiation”. Tiwari himself began eliminating the middlemen, selling directly to corporates. Along with other farmers, he hopes to rent a warehouse to store his produce so that he can sell to whoever gives him the best price.

Like Tiwari, agri entrepreneur Parth Tripathi, CEO and director of BeeHively Group & Krishna Agro, believes traders and commission agents will lose out the most with the passing of these bills, not farmers. "These people have strong influence in agriculture and are misleading farmers with wrong information on the bills," says Tripathi. According to him, APMCs don't allow easy entry for a new trader in the market yard to avoid building competition. "The APMC traders levy undue deduction in the form of commission charges and market fees on farmers," he explains.

While MSPs, APMC and private markets are three separate issues, they are intimately connected. "MSP is available to a farmer only in a procurement centre of the government, whereas the APMC mandi has its own price formation process," explains R Ramakumar, professor, School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences. In case a farmer cannot sell at his desired price in an APMC mandi, he has the option to sell to the procurement centre, and the MSP indirectly affects price formation of APMC, by acting as a floor. Ramakumar adds, "The problem is that the private market would be unregulated. The whole idea of having MSP as a floor for price formation will no longer exist. And prices are likely to be far lower than MSP."

Farmers like Sharanjit feel if MSP is abolished and there is no government procurement, private players are likely to offer lower prices than what they deserve. "Their aim will only be to make profit at our expense,” he says.

Like Singh, many farmers across Punjab say small farmers are unlikely to have any bargaining power over private players. "For this season, MSP for corn is Rs 1,800 per quintal. If you let corporations negotiate, they’ll bring down the price to Rs 600 or Rs 700. Add to that their ability to buy in bulk… they’ll stockpile our produce at negligible rates and then sell it in the market at a much higher price during a shortage. In all this, we will suffer,” he adds.

The government, however, says the vision is to create a new class of ‘agripreneurs’. Sanju Verma, economist and national spokesperson of BJP says, "Prime Minister Narendra Modi has categorically stated that the Farm Bills will have no repercussions on the prevailing MSP and public procurement practices."

Even so, people including Karanveer Singh, who is an arhityas (middleman) in Jalandhar's APMC markets, is unconvinced. “If they promise not to abolish APMC mandis, why don’t they give a written statement?” he asks. Punjab alone has 28,000 commission agents whose lives will be affected if the trade moves away from the mandis.

Some states, including Bihar, abolished APMCs in 2006. According to news reports, after the abolition of mandis, farmers in Bihar on average received lower prices compared to MSP for most crops. For example, against the MSP of Rs 1,850 a quintal for maize, most farmers in Bihar reported selling their produce at less than Rs 1,000 a quintal. “People in Bihar have faced consequences of this reform. I have friends there who had to give up farming and shift to Punjab in search of work, as they were being exploited by private players and could not earn enough to feed their families," claims Sharanjit Singh, the farmer protesting in Punjab.

According to Arun Singh, global chief economist at Dun and Bradstreet, creating ‘one market one nation’ through marketing reforms will only help grow the sector. "The low level of agriculture productivity has been much deliberated. Efficiency in marketing can drive up productivity, by giving farmers access to technology, encouraging investments, creating infrastructure, reducing wastages, bringing about standardisation and improving quality for exports," he says.

Farmers gesture as they block a national highway during a protest against farm bills passed by India's parliament, in Shambhu in the northern state of Punjab, India, September 25, 2020.

Farmers gesture as they block a national highway during a protest against farm bills passed by India's parliament, in Shambhu in the northern state of Punjab, India, September 25, 2020.

Image: Adnan Abidi/Reuters

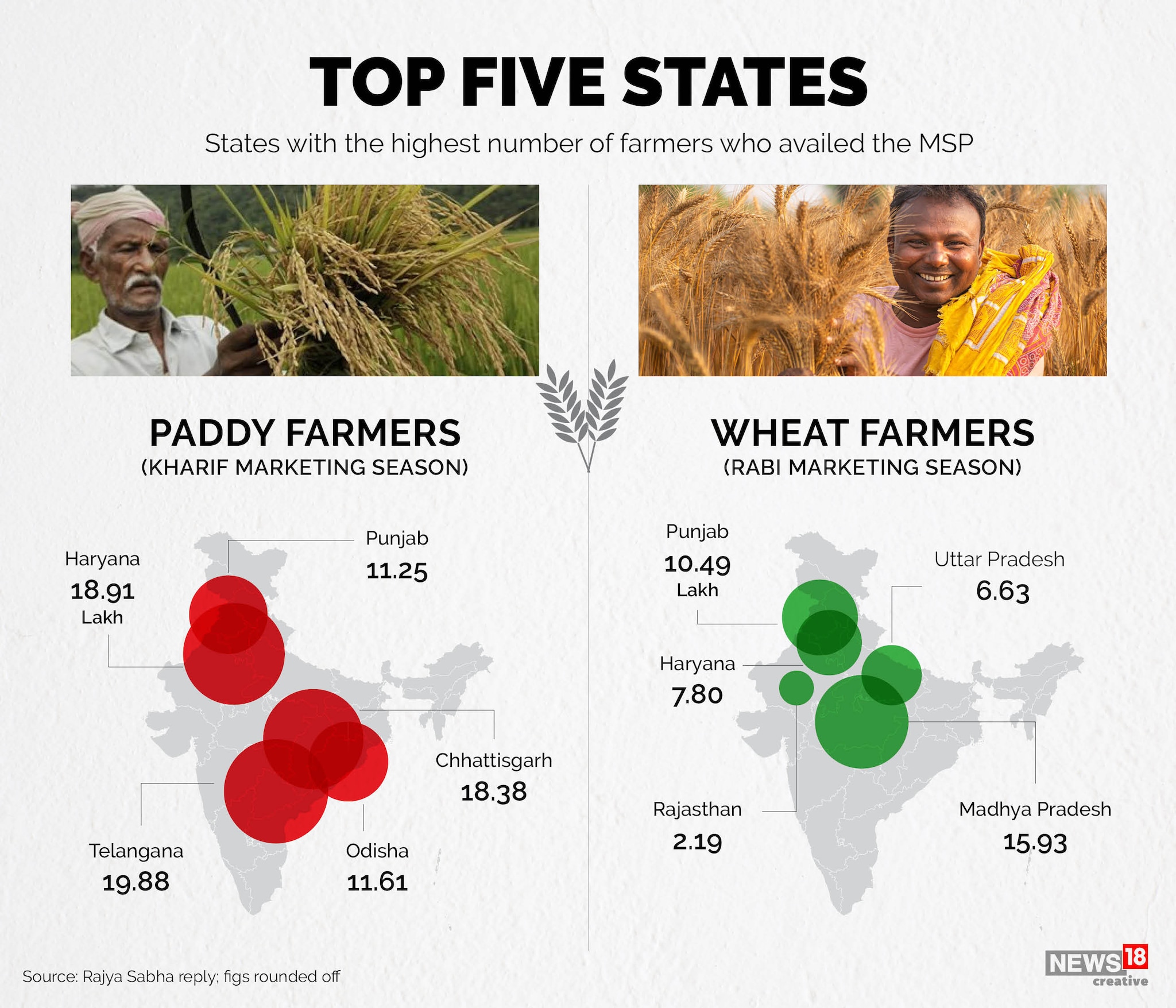

Punjab and Haryana in the limelight

The protests are predominant in Punjab and Haryana, since these states are the main contributors of wheat and paddy production. In 2019-20, government agencies in Punjab and Haryana purchased 226.56 lakh tonnes (lt) of paddy and 201.14 lt of wheat, whose value—at their respective MSPs of Rs 1,835 and Rs 1,925 per quintal—would have been Rs 80,293.21 crore.

“Punjab and Haryana have efficiently managed the MSP policies. Our farmers earn the value for their produce with a properly mediated mandi system," says Karanveer Singh, the arhatiya in Jalandhar’s APMC mandis. “Farmers get the due MSP even if their produce doesn’t match the required quality standards, which is very common as produce quality depends on various external factors. Do you think the private players will care about the farmers if the produce doesn't match their requirements?”

According to the BJP’s Verma, the ‘arhatiya’ system is more influential and deeply entrenched in Punjab than anywhere else in India. "Under the existing APMC mandi system in states like Punjab, APMC/mandi fees come to about 8.5 percent—market fee of 3 percent, rural development charge of 3 percent and middleman’s commission of 2.5 percent," says Verma, who claims that the 40,000 APMC agents or middlemen who operate in Punjab made over Rs 1,600 crore as commissions last year. "Additionally the State of Punjab, too, raked in over Rs 1,750 crore as mandi fees and a similar amount as rural development cess."

Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh told The Indian Express, "They [the government] never bothered to consult any of the major stakeholders before bringing the ordinances—they did not talk to the farmers’ representatives, they did not talk to my government, which represents the most important state in India’s food security chain."

Although the intensity of protests is higher in these two states, according to TISS professor R Ramakumar, farmers are angry across the country. "Even in a state like Kerala, where there is no APMC Act and no APMC markets, farmers are protesting because they still see that there it could lead to weakening of the MSP in the long run," he says.

Essential Commodities Act & Contract Farming

The amendment in the Essential Commodities Act will create a competitive market environment and prevent wastage due to lack of storage, says Tripathi, adding that "Removal of stockholding limits will attract private investment in the sector, especially in much-needed infrastructure such as cold storage, warehouses and modernised food supply chains.”

However, Ramakumar argues, "With the amendment, all ceilings on stock limits that existed for traders for those crops have been taken away. Earlier, these stock limits prevented black marketing and hoarding." According to the government, it is due to these stock limits that there is no private investment coming in, hence the amendment. "In my opinion, first, removing stock limits will not bring in private investment. And second, black marketing and hoarding will no longer be prevented," adds Ramakumar.

Another pain point for farmers engaged in protests is the fear of being exploited by corporates due to contract farming. According to BJP’s Verma, by allowing farmers to engage in contract farming, "they will have the freedom to sell their produce directly to food processors, aggregators or exporters, even before the harvest, at a pre-determined price, thereby insulating farmers from the vagaries of price volatility that agri products have to grapple with.”

Private Players: Competition or Threat?

In the current scenario, farmers have only been focussing on quantity and not as much quality, in desperation to earn. Which explains why productivity of Indian agriculture is poor—despite employing over half of the country’s total workforce, agriculture's contribution to GDP is under a fifth.

"This has limited innovation, especially for cereal crops. The farmers’ focus right now is maximum output and hence, maximum money," explains Tiwari. In his opinion, these Acts are likely to change that. "Price, in the long run—with the passing of these bills—will be determined by the quality of the produce instead of quantity," he adds. However, the farmers protesting believe the bill is likely to benefit private players only. “There is a high chance that corporations entering the market may initially offer us comparatively higher prices for our produce to lure us in, while giving the government enough to abolish MSP completely," explains farmer Sharanjit Singh.

.jpg)

Most agritech players, meanwhile, are all for the reforms. Amit Agarwal, CEO and co-founder of Mumbai-based startup AgriBazaar, feels that the pandemic has created greater urgency for small Indian farm-owners to shift to digital selling and buying. The startup has replicated the physical mandi to an e-mandi aggregator model, where once a farmer registers and uploads his produce, buyers can place orders directly.

"Alongside mechanisation, predictive technology will change the way forward for the Indian farmer and how he or she handles pre- and post-harvest produce. Digitisation of the entire agri-supply chain will gather pace as also increased automation, adoption of blockchain technology, machine learning and artificial intelligence," says Agarwal.

Similarly, Varun Khurana, founder of Otipy, a social commerce venture (B2B2C) by Crofarm—a farm-to-fork agri-tech startup—also feels farmers will benefit from better prices with more options outside mandis being available. "We've seen inbound from farmers increase, also horticulture departments of the various neighbouring states have approached us. This is a welcome move for agritech supply chain startups like us," he says.

Another apprehension is that there could be price fluctuations in the country for different kinds of produce under these ordinances. Amandeep Singh, secretary of APMC in Jalandhar Cantt, Punjab says, “This is not the right time to introduce these bills; our farmers lack the business acumen, unlike the corporates. There’s no immediate threat to MSP for the next couple of years, but once private players enter the market, they’ll create such circumstances that MSP wouldn’t be relevant. Farmers will have no option but to sell to the corporations."