Protecting Know-How In China: Process Is Simple And Complex

Previous studies fall short in providing a comprehensive understanding about successful IP protection activities that work

In 2011, almost a decade after admission to the World Trade Organization, the ability to protect intellectual property (IP) and other corporate know-how in China remains one of the most critical issues for foreign multinational corporations, especially for those doing business in the high-tech and service sectors.

Surprisingly little research has investigated IP protection outside the traditional litigation and mitigation approach. Previous studies fall short in providing a comprehensive understanding about successful IP protection activities that work. Our research intends to correct this.

We conducted more than 97 in-depth interviews with executives from 50 multinational corporations, IP protection specialists, business consultants and governmental agencies. Many executives were Thunderbird alumni or friends. We sought answers to three overarching questions:

• What are the key environmental issues for “IP Protection” in China?

• How are foreign and local companies protecting their IP in China?

• Are there “best practices” or common themes among companies?

New China realities

China is no longer simply the low cost “workshop of the world.” While China still manufactures most of the world’s toys, footwear and consumer electronics, during the past two decades exports from China’s high-tech industries grew from 6 percent to more than 30 percent.

In China multinational companies can no longer compete with offerings based on previous generation or “old” technology. They have to offer their most advanced know-how, despite the fact that for many China is synonymous with intellectual property theft. Consider the following incidents reported to us:

• Several years ago, an Intel employee in China took intellectual property to AMD, the company’s main competitor. The value of the theft was estimated close to $1 billion.

• Recently, a Ford employee took more than 4,000 confidential business documents and used them to secure a job with a Chinese auto manufacturer. Currently, Renault executives are being scrutinized for similar behavior.

• Pfizer has taken several trademark cases to Chinese and international courts and received a ruling that Viagra is a valid trademark. The courts ordered two Chinese companies to stop producing counterfeit pills. Pfizer still struggles with the enforcement of the ruling through local authorities.

What drives IP leakage?

China’s unique socio-cultural history contributes to IP theft in China. For example, students learn by copying their master. The perfect copy is considered a complement for the original. Further, there are very low marginal costs for IP theft (including very limited prosecution) compared to the costs associated with R&D. One general manager stated: “Wide spread IP leakage will persist until it is more expensive to copy than it is to innovate.” Finally, a high turnover rate of knowledge workers, well-educated middle managers, and engineers causes a constant “bleeding” corporate know-how.

The unfortunate reality is that in China, eventually all intellectual property leaks. Some leakage is faster and some slower. Success in China requires diligent control paired with pro-active dynamic management of IP leakage. Passive over-reliance on an immature legal system is ineffective.

IP protection that works

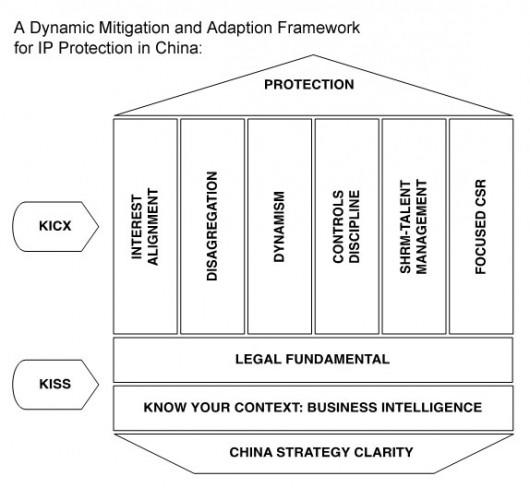

Despite challenges, many multinational corporations have high-tech investments in China and a fair number do a good job protecting IP using a variety of mechanisms. We found three specific levels of IP protection mechanisms that are required in combination for success, including:

• Explicit strategic clarity about a firm’s China activities.

• Establishment of a set of activities that follow core IP protection procedures, including context-relevant legal diligence and business intelligence—we refer to this as keep it simple (KISS).

• An intertwined arrangement of six dynamic organizational and managerial actions including stakeholder alignment with the aim of increasing complexity to such a point that not one single breach could create a threatening IP leakage situation—we call this keep it complex (KICX).

Our IP protection framework (see illustration) is characterized by a dynamic combination of simple and complex, static and flexible activities and practices. It should be read from the bottom up.

For effective IP-protection in China, firms must have context-relevant corporate and business strategies; they must have identified the critical IP that is required to execute these strategies; they must identify the right people (internally and externally); they must explicitly formulate effective operational, management and contingency processes; and they must develop an explicit awareness of timing and its impact on the other factors mentioned.

While these practices seem simple, more often than not, companies rush into China without considering these measures. We collected overwhelmingly rich evidence that this negligence usually leads to significant IP leakage. Incorporating IP protection tools and practices during the development of the business strategy provide the critical foundation upon which companies can build a robust IP protection strategy (KISS—keep it simple).

Once companies have established this foundation, the focus shifts to a variety of managerial activities (KICX—keep it complex) that introduce on one side complexity and ambiguity—they can’t understand how you do what you do–and on the other internal and external stakeholder alignment as dynamic elements of IP protection. We identified six effective activities including:

(1) Proactive Interest Alignment with regulatory institutions and individual government officials in the localities where the company operates;

(2) Disaggregation of IP components and core processes through organizational and physical separation of activities, vendors and know-how;

(3) Dynamism through continuously improving products and processes, in order to stay at the leading edge;

(4) Controls Discipline that rests on a strong organizational culture;

(5) Strategic Human Resources Management/Talent Management that makes the company a “great place to work”; and

(6) Focused Corporate Social Responsibility activity that makes the company a valuable, integral part of the local community.

The key driver here is the “complexity” that results from combining these multilayered activities. The effect is a significant slowing down of both opportunistic would-be IP thieves (including departing employees, suppliers, and customers) and organized illegal IP theft through espionage.

The use of socially complex processes, like talent management, extends the reduction of knowledge theft to the employee level, which is the most common conduit for IP leakage. Protection activities embedded in socially complex processes create ambiguity that provides a temporarily sustainable advantage.

Finally, the more onerous challenge for multinational corporations operating in China is to remain dynamic by configuring and reconfiguring the elements of the framework as the context evolves, devolves or shifts.

Best IP practices

In China, IP protection that goes beyond patenting and legal litigation is potentially the most important organizational capability for assuring long-term performance in high-tech and service firms. This requires that companies employ three sets of best practices:

(1) Get the fundamentals right including, strategy, deep contextual understanding, and the use of appropriate legal fundamentals.

(2) Develop and reinforce the 6 activities that are catalysts for dynamic IP protection.

(3) Build a control-based culture, processes anchored in social complexity, and do this with speed.

Andreas Schotter, Ph.D., is a Thunderbird professor of strategic management. Before embarking on an academic career, he was a senior executive with several multinational corporations. He has lived and worked in Europe, Asia and Canada.

Mary B. Teagarden, Ph.D., is a Thunderbird professor of global strategy and editor of Thunderbird International Business Review. She has lived and worked in 11 Latin American countries, five European countries and eight Asian countries — in addition to the United States and Canada.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from Knowledge Network, the online thought leadership platform for Thunderbird School of Global Management https://thunderbird.asu.edu/knowledge-network/]