A Rainy Day at Auschwitz

Walking through the Nazi death camps with history and imagination crawling up your back

It’s drizzling. Raindrops fall on the camera lens, spoiling the photographs. Besides, the sky is white. Not the blue that makes a good backdrop for pictures. I have to clean my lens every time I click.

I step into a large, darkish foyer. It’s crowded. A gang of college students is in a serious discussion. An anxious mother is running after two children. A small kid, dressed in a yellow jacket, is wailing. There are a couple of stalls, selling brochures, guidebooks and magazines.

I join a long queue for the site guides, pay nearly 50 euros and get a bit of green paper that I am supposed to stick on my jacket. “Your guide will join you there,” a lady at the counter points to a spot outside a door. I go there.

The trees sway to the wind. At a distance, there are rows of similar, sturdy, red brick buildings. The buildings look as if they are standing in attention, waiting for a giant to shout the next order.

I close my eyes for a couple of seconds, and then look around. A 60-year-old chill creeps up my spine.

The fences are electrified. There are watch towers. Three ominous words on a black iron gate say: Arbiet macht frei. Work makes you free.

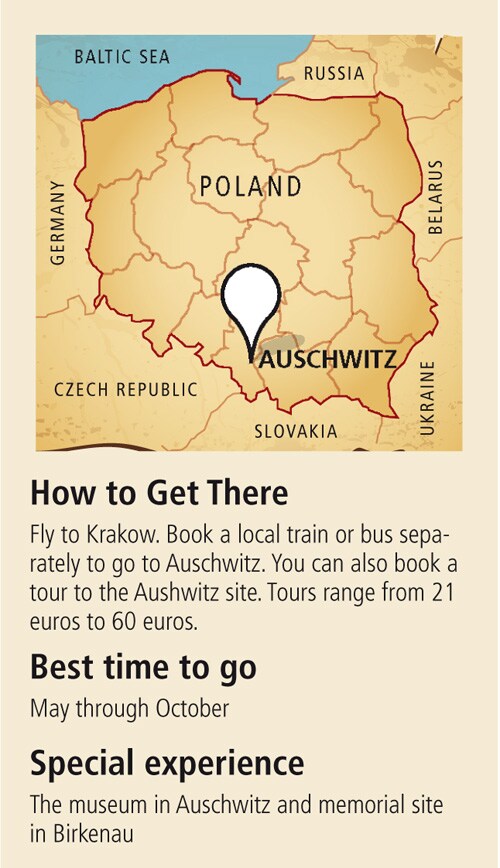

There is something about those words that evokes hope and fear at the same time. Work didn’t make most inhabitants free. Only death did. More than a million — Jews mostly, but also gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, political prisoners — were systematically killed here, just an hour and a half from Krakow, where church bells chime.

In the five years that Hitler’s most dreaded death camp was in operation, thousands of people were herded in, experimented upon, and exterminated. A few minutes ago, I was worried that the raindrops and white sky would spoil my photographs; I haven’t even stepped into the gate, and already I find that losing or gaining perspective is no longer in my control.

I follow my guide to one hall after another: Cells converted to a permanent exhibition. On the walls, there are photographs of people who had just arrived at Auschwitz; men and women, young and old. Some of them look straight into the camera, as if they are in a photo studio before a happy occasion, eyes bright with hope, and a sweet smile on their lips. A girl in her 20s, beautiful, dark hair, looks confidently at me. The text below the photograph says she was killed a day later. These photographs were taken during the early days. Later, as the camp scaled up its operations, they stopped photographing people; cost-cutting.