Will Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana take us the US Health Care Way?

The Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna has been lauded by the World Bank and the UNDP for its success. But is it the way forward for India?

In June 2011, the World Bank came out with its first-ever review of social welfare policies in India. For most part, the review panned the policies for their faulty design and sloppy implementation. However, there was one exception—the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna (RSBY), or the national health insurance scheme.

“…the RSBY health insurance programme for BPL households is path-breaking in its design and has pioneered approaches to delivery which provide a model for other public programmes,” it stated.

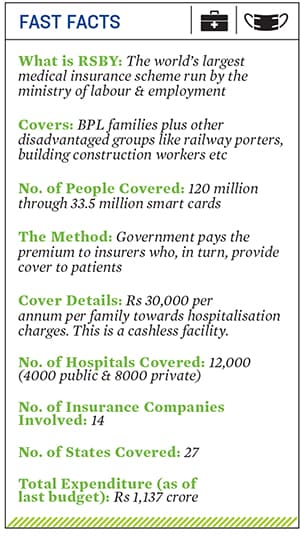

The scheme is today the world’s largest medical insurance programme covering over 120 million poor people in the country (see box). It provides a maximum cover of Rs 30,000 to each BPL (below poverty line) household in the country. However, the insurance is available only for in-patient care (or hospitalisation).

The RSBY has received rave reviews even from international organisations. The GIZ (or the German Agency for International Cooperation that, along with the World Bank, was involved in designing the scheme) in its January 2013 report has found that based on data from three states—Bihar, Uttarakhand and Andhra Pradesh—90 percent of the respondents were satisfied with the scheme.

So, it comes as a surprise that academics and health experts alike see its expansion as the greatest threat to achieving universal health care in India.

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

Sudha Pillai, then the labour and employment department secretary, led the design of the scheme. In 2008, she says, the RSBY—which was part of the UPA’s Common Minimum Programme—was started to provide social security for workers in the unorganised sector. This was after the health ministry washed its hand of the scheme, stating it already had a lot on its plate.

Pillai used a similar government-funded medical insurance proposal from the Kerala government and the home ministry’s efforts to provide smart cards to citizens in the border areas to come up with the RSBY model. Since its inception, RSBY has grown rapidly, both in terms of its coverage as well as budget allocations, the latter being quadrupled to Rs 1,137 crore (2013-14).

Over the years, RSBY has garnered an enviable position in India’s policy space. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and International Labour Organization (ILO) picked it up as one of the top 18 social security schemes in the world.

Interestingly, the scheme has been championed by non-Congress states like Chhattisgarh, which has expanded the scope of RSBY beyond the BPL category to cover every citizen. On the other hand, the worst performers are Congress-ruled states Delhi, Maharashtra and Rajasthan.

IS THE DIRECTION WRONG?

Despite such eagerness shown by the governments both at the Centre and the states, observers feel RSBY is pushing India’s health care into a deeper mess. The criticism against RSBY is at two broad levels.

According to experts like Sakhtivel Selvaraj of the Public Health Foundation of India, the first concern is that, in the absence of a strong primary and secondary health infrastructure, it increases the tendency among patients to get hospitalised at the first instance. As an off-shoot, it leads to increased frauds. Various studies and reports have shown how empanelled hospitals did not have adequate facilities, or how hospitals conducted unnecessary hysterectomies on patients to make easy money through the cashless insurance schemes.

Anil Swarup, the additional secretary in the ministry of labour and employment and the man heading RSBY at the Centre, is aware of such problems. “We are addressing those issues. We have de-empanelled 270 hospitals in the country. Tell me one scheme in the country which has taken such action. We must not throw the baby with the bath water,” he says.

Swarup’s team has identified 40 triggers that will reduce such frauds. If a hospital, for instance, has a bed capacity of 15 and on a particular day admits 20 people, the system will raise an alert.

Second, as more and more people use insurance to pay their bills, insurance companies will ask for higher premiums from the government. In time, this trend could make the scheme unviable. “Take a look at Kerala where the premiums have trebled in the last four years due to high utilisation rates,” says Selvaraj of PHFI.

Researchers like Sulakshana Nandi of the People’s Health Movement, India, and others quote the high premiums in the US and show that they are rising in India too. Her research also shows that the higher disease burden on the poor is for outpatient care and drugs rather than hospitalisation. Selvaraj’s 2012 study corroborates the claim and finds that out-of-pocket expenses for the poor have been increasing.

Moreover, hospitals complain that the rates fixed by the government are not viable. Dr Narendranath V, chief administrator of MS Ramaiah Memorial Hospital in Bangalore, says, “The government is working on the basis of the CGHS [Central Government Health Scheme] price list of 2007. In those days, a hernia repair cost Rs 5,000, but today it costs Rs 11,000.”

Proponents of RSBY feel India is far from US levels of spending. “Higher utilisation shows the success of the scheme. We should not speculate what can happen tomorrow…a meteor can also fall on India,” says an exasperated Sudha Pillai.

Ironically, hospitals complain about low pricing, yet, at the same time, put “political pressure” to get empanelled. Truth is, most private hospitals try to cherry-pick patients and diseases that can fetch them more money through treatment.

Public Vs. Private

Should health care be provided through government channels or through giving out medical insurance? Swarup says that while you could combine both approaches, it would be better if the government manages the demand. India has failed miserably in managing supply since its independence. Providing insurance not only gives the poor a chance to access private care but also provides a business case for private players to service remote areas.

“It is fine to say the government should invest in primary health care, but where are the doctors?” asks Vikas Sheel, former Chhattisgarh health secretary. The state once had a sanctioned strength of 2,000 but had to work with only 600 doctors despite the government offering salaries as high as Rs 1 lakh per month. “The incentive structure cannot work because of the huge demand-supply gap. For this, the private sector can always outbid the government for medical staff,” he says.

DEVIL AND DEEP SEA?

Anil Swarup feels wronged as RSBY, in his opinion, is being unjustly blamed for the problems in India’s health care system. “RSBY does not aspire to create a health infrastructure. It only aspires to put money in the hands of the patient so that he may not have to spend from his pocket if he finds a hospital.”

As of now, India is stuck with an odd choice—accept a reasonably effective RSBY which may, at best, provide a band-aid to India’s deep-set health problems and may turn out to be unviable in the long run, or try for public provisioning of health care and risk failing even more miserably.

(Additional reporting by Nilofer D’Souza)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)