Softbank: Harder battles

Why the Japanese investor will have to revisit its gambit of investing in the bellwethers of Indian ecommerce

SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son wants to be known as a crazy guy who bet on the future

SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son wants to be known as a crazy guy who bet on the futureImage: Yuya Shino / Reuters

Flipkart was the remedy to most of his problems. While the firm spent the better part of 2015 and 2016 dodging Amazon’s artillery, Flipkart was still India’s most valuable startup, valued at about $11 billion and the market leader by a fair margin. It was also scripting a turnaround under the leadership of Kalyan Krishnamurthy, an emissary of the firm’s largest shareholder, Tiger Global Management.

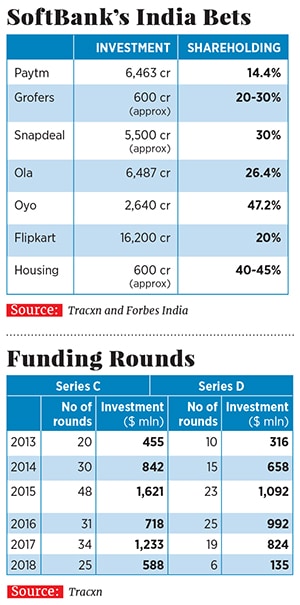

It looked like Flipkart could be the right bet to salvage some of SoftBank’s earlier misadventures in India, such as Snapdeal and Housing. Pat came the money from SoftBank’s $100-billion Vision Fund—a mammoth $2.5 billion cheque, the single largest funding round by a homegrown startup. SoftBank ended up owning close to one-fifth of Flipkart through a mix of primary and secondary transactions.

The deal was in line with Son’s vision to buy into the biggest businesses in promising markets. “We want to support innovative companies that are clear winners in India,” Son had said of the deal, which Flipkart co-founders Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal had described as a “monumental moment”.

In May 2018, eight months after SoftBank’s maiden cheque to Flipkart, came another monumental moment, not just for Flipkart but also for India’s fledgling startup ecosystem that is notoriously starved of profitable exits. Walmart Inc acquired a 77 percent stake in Flipkart for $16 billion in the world’s biggest ecommerce deal, handing out mega exits to a bunch of Flipkart investors, including SoftBank, which is slated to make $4 billion from the sale, or a 60 percent markup on its investment. Son, for his part, was still weighing his options at the time of writing, regarding selling SoftBank’s stake in Flipkart. SoftBank may well hold on to the Flipkart stake for a little longer, and exit at a predetermined price in the months to come to avoid tax liabilities.

If—some would prefer to say ‘when’—SoftBank does exit Flipkart, that clearly isn’t how things were supposed to pan out. The plan, say people in the know, was to invest more in Flipkart, increase its stake and see to the end the firm’s battle with Amazon. Also, possibly merge Flipkart and Paytm, where Alibaba is the majority stakeholder, to create a behemoth big enough to fend off Amazon. But, for the rest of Flipkart’s investors, some of whom had stayed put for close to a decade, there was no better outcome than an all-cash sale to Walmart. SofBank declined to comment.

To be sure, SoftBank, one of the largest shareholders in the company along with Tiger Global Management—both hold 20-25 percent in Flipkart—favoured a sale to Amazon, which had made a counter-bid for Flipkart in the wake of Walmart’s overtures, but eventually gave in to the majority’s wish. A stake in Amazon against its holding in Flipkart could have still been a plausible alternative for SoftBank, given both Son and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s penchant for long-term bets. But that was not to be. Its vision of slipping into the driver’s seat in India’s burgeoning online retail segment has taken a beating, at least for now. The next Alibaba moment for SoftBank, especially in India, is still some time away.

“Given the stature of SoftBank and the size of the fund, it is in their interest to invest in and stay invested in the biggest companies in the markets they go after. Their mindset is not to exit in six months and that would be a suboptimal approach for a fund of that size,” says Shubhankar Bhattacharya, venture partner at Kae Capital.

SoftBank, on an average, has held investments for about 13.5 years.

This is not the first time things did not pan out as per plan for SoftBank. Snapdeal, in which it had pumped in about `5,500 crore for an approximately 33 percent stake, is a shadow of its former self and another investee company Housing was sold for a modest $70 million to PropTiger, much lower than its peak valuation of about $240 million. SoftBank’s bid to sell Snapdeal to Flipkart for about a billion dollars also came a cropper after a protracted boardroom battle.

Now, all is not well between SoftBank and one of its most promising bets in India, Ola. Bhavish Aggarwal, co-founder and chief executive at the $5-billion company, had amended the company’s Articles of Association last year to clip SoftBank’s wings and pre-empt any manoeuvre by SoftBank to change the company’s direction without Aggarwal’s approval. All this despite SoftBank being the largest stakeholder in Ola with about 27 percent holding.

In effect, SoftBank cannot buy more equity shares in Ola without an approval from Aggarwal and co-founder Ankit Bhati. Besides, SoftBank, which has one board seat—David Thevenon represents SoftBank on Ola’s board—can appoint another director if the person “is reasonably acceptable to the founders and all other shareholders”. However, it cannot appoint a second director if Softbank ends up owning more than half of the preference shareholders in Ola’s current funding round.

Aggarwal has already exercised his rights. While SoftBank ended up investing $250 million in Ola’s last $1.1 billion fundraise, the Japanese conglomerate was willing to put in more capital. Aggarwal resisted. Ola managed to rope in Tencent, which wrote a $400-500 million cheque.

Last year, Aggarwal also blocked an attempt by Tiger Global Management to sell a part of its stake to Softbank. Another clause in the Articles of Association states that Aggarwal and Bhati will need to sign off on any transfer of equity shares by Ola’s investors, accounting for more than 10 percent of the company’s share capital.

“SoftBank doesn’t have an ownership in the businesses that are much bigger and they have to fend off other deep pockets. They don’t have that kind of a grip on most businesses that they have with, for instance, Oyo, with sheer ownership,” says an executive at a venture capital fund. SoftBank owns about 47 percent of Oyo, a budget hotel network.

Image: Joshua Navalkar

SoftBank may have to take such setbacks in its stride and move forward. Else, the sectoral leaders will find other suitors, the way an Ola or a Flipkart did. “There are more pockets of capital coming into India. About 18 months ago, they were the only big boys in town, but it is no longer the case,” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital. “SoftBank has shown a lot more commitment than the other guys, but directionally it seems like India will be a global battlefield. This is a deep and open market. It is logical that the other large pockets of capital will not allow one player to mop this up.”

With frothy valuations no longer the order of the day, a whole lot of bulge bracket financial and strategic investors, capable of writing $50-100 million cheques and beyond, are lining up to invest in India. For instance, Alibaba and its affiliates have bought into food startup Zomato, logistics startup Xpressbees and online grocer BigBasket, apart from owning much of Paytm. Tencent is an investor in education startup Byju’s, health care startup Practo, Ola and Flipkart. Naspers, which made a whopping $10 billion by partially selling its stake in Tencent, is an investor in food delivery startup Swiggy. A sizeable part of its spoils from the stake sale is likely to be channelled into India. Then there are the likes of Microsoft, an investor in Flipkart and Google, which is an early backer of hyperlocal delivery startup Dunzo and fashion startup Fynd. Google is also considering a $1.5-3 billion investment in Flipkart.

The likes of Samsung, Ward Ferry, Mirae Asset Management, sovereign funds of Saudi Arabia and Orchid Asia among others are also actively looking to invest in Indian startups.

“Certainly there are more late-stage investors now than we have seen in the past. There was a time around 2014-15, when the only people writing late-stage cheques were Tiger Global and SoftBank. Late-stage capital can only be good for the ecosystem. We had a phenomenon of companies starved of capital after showing significant growth and improving unit economics as well. Only a handful of companies had access to that kind of capital,” says Ritesh Banglani, partner at Stellaris Venture Partners.

Unlike before, startups may not be willing to give an arm and a leg to get SoftBank on board. Take for instance, Housing. The company had plans to raise about $40 million from investors, including Falcon Edge Capital, at a valuation of $150 million, when SoftBank swooped in with an offer to pump in $100 million, valuing the two-year-old company at approximately $240 million, Forbes India has reported in an earlier edition.

Fast forward to 2018. SoftBank, which had evinced an interest in investing Swiggy, is competing with investors such as Alibaba, Meituan Dianping, Coatue Management, Naspers and Tencent for a stake. People in the know suggest SoftBank may lose the bid. “Nothing may happen now, but SoftBank is lining up for the future. For Swiggy, the question is how much was available for SoftBank to be taken. You already have Naspers and they were willing to do a good chunk of the round and bring their partners in. Swiggy isn’t looking for $500 million now,” says an investor in Swiggy. At the time of writing, reports indicated that SoftBank had begun talks with Swiggy rival Zomato.

At this juncture, SoftBank’s India play is somewhat constrained by its fund size. Investing out of a $100-billion corpus essentially means the firm needs to invest a couple of hundred million dollars in the least. Unfortunately, not many Indian startups are big enough to absorb such mammoth capital infusion yet.

“It looks like SoftBank wants to write $200 million cheques, for which the companies need to reach a certain threshold. Today, there aren’t many startups who warrant $200 million, but it will be the case in two years,” says Alteria Capital’s Murali. “I think either they have to come in earlier and start writing smaller cheques or they have to outprice the competition.”

Son could as well do that. Anything for a slice of the world’s most promising companies. After all, he wants to be remembered as “a crazy guy who bet on the future”.