Amul's going utterly butterly digital

Amul, a brand almost as old as the nation itself, is gearing up for a phase of growth that includes many of today's tools of disruption, including apps and ecommerce. The biggest assets, though, continue to be its dairy farmers

RS Sodhi, MD, GCMMF

RS Sodhi, MD, GCMMF Image: Mayur D Bhatt for Forbes India

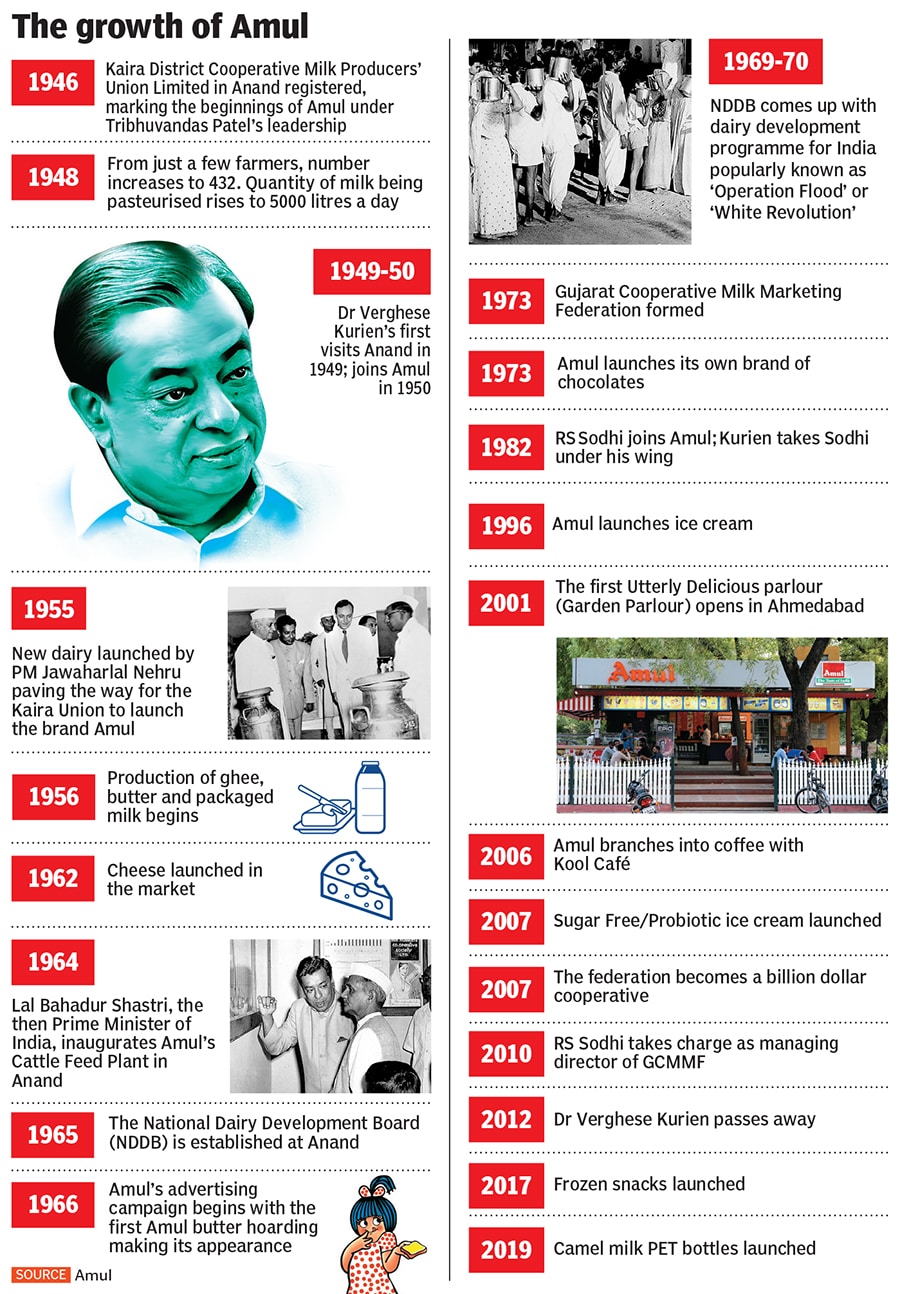

Fifty years ago, the four-year-old National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) in Gujarat’s Anand flagged off what went on to become the world’s largest dairy development programme. ‘Operation Flood’ or ‘White Revolution’ had one objective: To take the Amul model out of Gujarat and replicate it across India. Amul, of course, was the brand the milk farmers of Anand’s Kaira district had launched to process surplus buffalo milk—a first in the world—into powder, butter and cheese. This was possible thanks to a dairy that was inaugurated in 1955 by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

From an era in which women could be seen lining up outside a shed in Kaira to deposit milk to the age of ecommerce, the Amul brand has sustained, thrived and evolved. Delivery boys sporting Amul T-shirts are a common sight on the streets of Ahmedabad, going door-to-door to deliver its products to customers who order online. What started as Verghese Kurien’s accidental tryst in the milk business—he had left a government job to start Kaira’s milk cooperative movement along with freedom fighter and farmer leader Tribhuvandas Patel—today sells over 80 products with dairy at the core.

A lot, though, has changed in the past 73 years. “No educated girl in the 21st century wants to marry a dairy farmer who has 20-30 animals,” grins RS Sodhi, managing director of the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd (GCMMF), which manages the Amul brand and is collectively owned by some 3.6 million milk producers in Gujarat.

“The youth no longer find dairy farming sexy enough,” adds Sodhi, who Kurien took under his wing in the early ’80s and who became GCMMF’s chief in 2010. The next generation of farmers has been going to the big cities for education, and most are not too keen to return. Sodhi is counting on technology to encourage them to have a go at running their family dairy farms. For, instance, automated milking machines have been brought in in the dairy farms. Amul’s 79 factories across India are also keeping up with technology. And then, there is ecommerce.

In Ahmedabad, consumers can have products delivered by placing orders online on Amul Online, an app and a website. Locate Amul is another app that helps sales executives find distributor information of Amul parlours, of which there are some 8,000 across India. Though Locate Amul is for internal sales executives and distributors only, it has the potential to be used for hyper-local delivery at a later date. Says Sodhi: “Our next phase will be near-commerce, whereby customers can order on Locate Amul itself.”

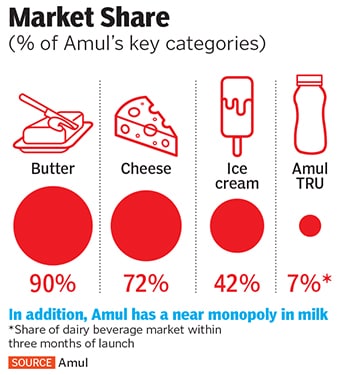

Along with the digital push is the inevitable entry into new categories. A market leader in milk, cheese and butter, Amul has expanded into beverages, chocolates, sweets and now even bakery. Abneesh Roy, executive vice president at Edelweiss Financial Services believes, “To survive in the crowded consumer market, Amul needs to constantly innovate.” Products like Roti Softner, Camel Milk and Amul Tru are evidence of that. Amul Tru, for instance, is a combination of milk and fruit in a ₹10 bottle. GCMMF Chief Operating Officer Kishore Jhala adds that the Roti Softner “comes from the simple idea of allowing rotis to remain soft for a longer time. In the old days, when we needed to carry rotis for long journeys, our grandmothers would add milk to them; this is the same concept.”

Amul has also begun selling fresh bread and butter cookies in a handful of markets. One reason for the latter is the suspicion in some consumer minds that some biscuit makers were passing off the cheaper palmolein oil as butter. “So we decided to launch our own butter cookies, where you can actually taste the butter,” says Sodhi, adding that people are willing to pay a premium price for these cookies simply because they taste better.

However, Roy of Edelweiss feels pricing might prove to be an issue over the longer term. “India is a value-focused market; even if prices are higher by 5-10 percent the customer will prefer the lowest priced product. In this category (butter cookies), I see Amul as being a very niche product, and not having too much scale unless the pricing is rectified,” he says. For butter cookies, Amul is setting up one plant each in the east, south and north. Sodhi, on his part, is quick to clarify that “we are not going in as a big national player in all of bakery [apart from butter cookies]”.

Mithai is likely to be a bigger bet—Amul has set up production units in Anand and Surat in Gujarat, and plans to gradually expand nationally.

Amul has a 90 percent market share in butter

Amul has a 90 percent market share in butter “We noticed that the quality of rasmalai (an Indian dessert) in the market was not very good. We launched it, and hit ho gaya (it became a hit),” claims Sodhi. As in butter cookies, here too Amul is riding on the trust quotient, as consumers suspect adulteration by neighbourhood mithai sellers. “Mithai is nothing but dairy, it’s no rocket science,” says Sodhi. The message is clear: Amul can be extended to any product that has milk at its core. Currently, the company is working on ways to increase the shelf life of these sweets.

If milk is at the core, so are the principles on which the brand was founded, the main one being getting farmers the best price. For instance, when Amul tentatively launched chocolates in 1973, the cocoa farmers of Kerala and Karnataka approached Kurien to find a way to get them fair prices. That was the cue to go the whole hog in a space in which Cadbury ruled the roost. Though that may not have worked in terms of market share—Cadbury is a clear leader with a 66 percent share, as per news reports—Sodhi has zeroed in on dark chocolate as a niche, where Amul claims to be the leader with a 65 percent share. Dark chocolate, however, is just 6 to 7 percent of the total market, though it is growing at a healthy 15-20 percent year-on-year.

So far, Amul has had a successful run thanks to great leadership. But what next after Sodhi? Sodhi, who is 61, expresses his concerns: “Amul has been successful because of the wisdom of its farmers and professionals. But we need to figure out how we will continue to remain successful.”

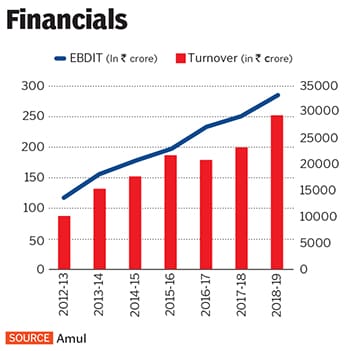

Fresh milk products are still the primary business, which brought in roughly 50 percent of Amul’s ₹33,150 crore sales turnover in fiscal year 2019. And the opportunity to grow in this segment is still massive, what with the organised sector accounting for just $28 billion (approximately ₹2 lakh crore) of the $100 billion (approximately ₹7 lakh crore) industry. While the overall Indian dairy industry has been growing at about 5 percent year-on-year, the organised dairy sector is growing a lot faster: At 13-14 percent.

In 2010, when Sodhi took charge as MD, Amul had a turnover of ₹8,005 crore. In an interview to Business India then, he declared that he was aiming at ₹30,000 crore by 2018-19. He’s gone beyond that, but the challenge clearly is to keep growing at a time when competition from both local and global players is intensifying.

Sodhi has a strategy for Amul’s next phase of growth: Take on regional brands available in friendly neighbourhood stores in smaller towns. He knows that consumers find comfort in such labels of fresh products available close to home. “Local players are big competition in terms of the product, packaging, distribution and brand building,” admits Sodhi. Eating into their share by winning the trust of consumers in these markets is key to taking Amul deeper into India.

Amul has zeroed in on dark chocolate and has a 65 percent market share in the category

Amul has zeroed in on dark chocolate and has a 65 percent market share in the category For instance, though in the ice creams category local brands like Arun, Dinshaw’s, Vadilal and Ramani Ice cream call the shots in their respective markets, Amul has been giving them a run for their money. Amul is the market leader in ice creams with a 42 percent market share.

Amul’s weakest link is the south, with many of its products not available in this region. “My sense is they will have to work like any late entrant, where they target any niche market, like the premium end, and then start by gaining a foothold in the mid and lower end of the market,” says Roy. Ice creams and butter-based bakery products may be Amul’s best bets to make deeper inroads south of the Vindhyas.

Another concern is the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade agreement between Asean and six other countries, for reducing or eliminating tariff and non-tariff barriers on imports and exports, which has many Indian farmers and manufacturers worried. Sodhi explains why. “Many of these countries want to dump their milk in India. New Zealand (one of the countries in the proposed partnership), for instance, has 10,000 farmers whose incomes will double, but what about the 10 crore farmers in India, whose income will halve?” Amul is working closely with the government in the hope that the RCEP is not signed. Other threats are the emergence of vegan products (non-dairy) and cheaper versions (like the palmolein oil biscuits).

GCMMF is unlike most private sector companies, whose main objective is to churn out profits by cost-effective sourcing of raw material. That’s because the cooperative’s shareholders are also its suppliers. And the farmer’s well-being is central to every strategic decision taken, often a bigger priority than market leadership.

At a time when the agri-economy is in distress, Sodhi believes that dairy “acts as an insurance for farmers, insulating them from fluctuations and shocks (in the agri sector). This is often the only cash crop that they have.”

Sodhi takes pride in having a business model that steers clear of government or private investor funding. Reason? A possible conflict of interest between the farmers and the investor or government.

He points to the example of one of Australia’s largest cooperatives Murray Goulburn, which got listed in 2015. What followed was a series of conflicts between producers and investors; a few years ago the investors decided to sue Murray Goulburn and its board for allegedly misleading them ahead of the fund-raising. “Eventually, farmers started leaving the cooperative and, it was bought over by Canadian dairy company Saputo in April 2018,” says Sodhi. The cooperative movement in Australia has petered out and in New Zealand, too, private investors have entered Fonterra, the world’s largest dairy. “We will never make this mistake,” assures Sodhi.

In fiscal year 2019, Amul procured a mind-boggling 230.08 lakh litres per day. “Six years back, we were the 18th largest dairy in the world, today we are the 9th largest. In three to four years, we plan to be in the top five,” promises Sodhi.

Kurien strongly believed that Amul’s biggest asset were its people. Sodhi is ensuring that Amul thrives by continuing to unleash the energy of those assets. He also has to groom a successor with a similar mindset.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)