How Altair engineering has evolved, from software to sparks

Altair Engineering commercialised computer-aided engineering in the Big Auto era of the '90s. How is it placed for the age of electric and autonomous vehicles?

James Scapa, co-founder, Altair Engineering

James Scapa, co-founder, Altair EngineeringJames Scapa’s knack for morbid humour was on display in Bengaluru in June. The 62-year-old co-founder of Altair Engineering started the company in 1985 to serve the automotive industry. It was a time when manufacturers and suppliers grew on a mass production model, synonymous with Detroit—to eventually consolidate or declare bankruptcy. Against that backdrop, Altair’s focus was decisively on building software products for manufacturers who struggled to shift to new opportunities because of large volumes and hardware. This was as true of supercomputers, as it was of auto manufacturing.

“Hardware companies become product commodities. I collect mugs of dead computer companies,” Scapa told an audience during a panel discussion on ‘Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Product Life-cycle’ at Conrad Bengaluru. The tone was deadpan.

“I don’t have a Compaq mug,” he tells Forbes India later. “I have a lot of mugs (more than 20 complimentary gift mugs with names like Cray and SGI on each) from all the hardware companies of the past 35 years. They all had specialised hardware, whereas software is really where the value ended up being. That’s why many (auto and technology) companies are now trying to develop their own software—operating systems, voice recognition, or simulation technologies for autonomous driving.”

Altair has evolved into a $396-million (₹2,840.9 crore) software firm at the intersection of technology and large industries like auto and aerospace. That’s why Scapa was hosting the Altair Technology Conference in Bengaluru, which featured experts from companies like Robert Bosch, Bharat Forge, Defence Research and Development Organisation, and Boeing. The two days were a deep dive into what lies ahead for industries getting disrupted by connected services, and trends like electric mobility, and the Internet of things (IoT).

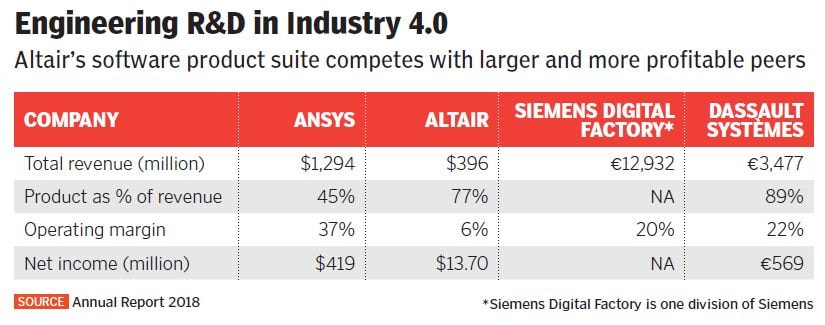

According to V Sumantran, chairman of auto advisory Celeris Technologies, Big Auto has globally moved its focus significantly from mechanical systems to electrical and electronic systems with software. “The former has not diminished in size, but the role of software and electronics has overtaken the quantum of work on the mechanical side,” he adds. With engineering R&D dollars overwhelmingly behind software and electronics, niche software companies like Altair, Ansys and Dassault Systèmes are not complaining, even as other equipment manufacturers (OEMs) worry about their investments in internal combustion engine (ICE) technologies.

Scapa is no ordinary journeyman in this attritional landscape. In November 2017, he took Altair to a successful public listing on the Nasdaq, four years after buying out the stake of growth equity firm General Atlantic in the company. “We had brought in private equity in 2004 because of my partners (George Christ and Mark Kistner)... one had retired already and the other one was to retire,” he recalls.

In 2011, Altair and the $1,294-million (₹9,283 crore) Ansys started eyeing the electric mobility and autonomous (self-driving) vehicles opportunities. Computer-aided engineering (CAE) to simulate and analyse vehicle development programmes is now seen as a market that will touch $7.8 billion by 2021, according to CIMdata, a consulting and PLM (product lifestyle management) research firm in the US. “To compete at the scale Altair wants to, we needed much more access to capital. So, the choice I saw was: To sell the company—I had many offers—or just say I am going to raise money, and make it a public company,” Scapa says.

In June, Altair raised another $230 million from the public markets. It had acquired 11 companies in the run-up to its IPO in 2017, buying strategic IP assets, and approximately 200 developers with expertise in electronics, material science, crash and safety, industrial design and rendering. In size, it is the smallest (see table) of the CAE industry. But Scapa thinks the force is with him because of Altair’s R&D engineering base in India.

New Horizons

The company had begun to invest in India in 1992, but struggled for years to integrate operations with the US headquarters. “The reason was my team in the US was not as supportive of offshoring,” says Scapa. “But over time, the mentality changed.” The India unit employs around 650 people.

By 2007, many in the offshore R&D industry heard about the global development Altair promoted, as engineers from India worked on developing HyperMesh, Altair’s flagship simulation software for analysis of stresses and strains in vehicle structures and parts. In contrast, Siemens and Dassault Systèmes were still perceived to be centralised to their global headquarters. And Siemens was acquiring successful peers of Altair like Unigraphics.

“HyperMesh was developed in the US by Altair, but partly by a whole lot of Indian engineers from Bengaluru. Altair has done well world over, and grown as a globally-integrated software and services company,” says a former head of a leading auto engineering services firm in India. The American firms have been more successful in transferring skill and talent around the world, which meant taking quality software engineers closer to customers in developed markets.

“ You need to come out with more and more strategies to light-weight the EV structure. That’s another huge opportunity that we are pursuing right now.”

Vishwanath Rao, Managing director, Altair, India

Scapa says there are now a lot of projects that are led from India. “With offshoring, we are moving a lot of our key guys back to the States. But our teams here are involved with the machine learning unit in Greensboro, a city in North Carolina. So, India is absolutely a leading market for software development,” he explains. “It is also a leading market for product sales. The team here is a powerhouse.”

Vishwanath Rao, managing director of Altair in India, is a case in point, having worked with the company for two decades. He breaks down the electric vehicle opportunity, knocking at the door of every ICE automaker, into three broad areas. “The first is to design the motor and simulate it for automakers to understand what kind of impact the motor has on the structure of the vehicle itself,” he says. “The other part is: How do you design the motor itself, for a given torque rating or a certain level of performance?”

The third area for electric vehicles is electromagnetic interferences. “There are so many cables, electronic devices, boards, which are all over the place. There is interference of signals, which affects the performance of all these devices. So we perform electromagnetic simulations using software to understand how do you optimally place all these devices within a car and shield any radiations to make sure it doesn’t affect the vehicle performance,” Rao explains.

India First?

The whole architecture of the vehicle will change, which has implications to invest for automakers and component suppliers. “If you knock off the IC engine from the front portion, automakers have so much more freedom to decide how they want to lay out their vehicle. But where do they want to put the motor, and battery. It gives us a lot of opportunity to come up with new architectures,” Rao says. While electric vehicles have fewer parts, they are heavier than an ICE vehicle because of the battery weight. “So you need to come out with more and more strategies to light-weight the entire structure. That’s another huge opportunity that we are pursuing right now,” Rao explains.

This has piqued the interest of many engineering R&D services leaders in India. Samir Yajnik, executive director at Electrodrive Powertrain Solutions, says: “Companies are now moving from software products to physical products, which means a combination of hardware and software because of autonomous and connected vehicles.”

With the government push in India to migrate to electric vehicle platforms, India will be a market and development centre for electric mobility. Yajnik says development of creative e-mobility applications—how it is connected to an ecosystem of two-wheeler, three-wheeler and four-wheeler markets—is going to be humongous. “The opportunity is to build products relevant to the local market because India could be a huge consumer of what is going to be physically produced,” he points out. It’s not something Altair wants to miss out on.

Scapa is confident Altair has the wherewithal—variety of products and experience—to help global OEMs make the shift to electric and autonomous technologies, while reducing their costs on vehicle development. Patience is vital, he says. In 2008, when automakers like General Motors and Chrysler were in the doldrums, Altair saw what a complete downturn was. Scapa’s response was humane.

“We were flat. So we did a lot of things to help some companies having challenges, in terms of pricing and other things. We also did free training. There were a lot of people laid off during that time. We did free training programmes on how to use our products for engineers to gain skills. That would make them more valuable in a future economy, right?” Scapa says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)