Indian board games take political, social hues

Board games are being designed to simplify various issues of the day, but can they achieve scale and impact?

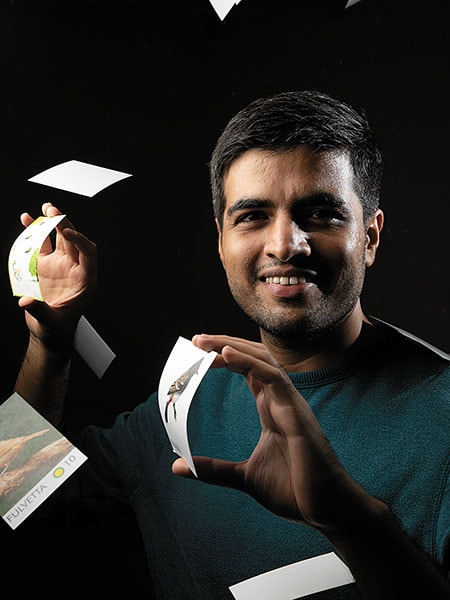

At Fields of View, Bharath Palavalli and team design games on various social issues

At Fields of View, Bharath Palavalli and team design games on various social issuesImage: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Seven years ago, when Bharath Palavalli decided to solve some of the world’s most pressing issues by playing board games, people looked askance at him. In 2012, the Bengaluru-based researcher co-founded Fields of View (FoV), a think-tank that simplifies and attempts to solve complex socio-economic issues through a series of games and simulations. From garbage management and urban mobility to migration and gender disparity, the team designs games to engage students, voluntary organisations, policymakers, researchers and the common public.

One of FoV’s popular board games called ₹ubbish, for instance, gets four to six people to become managers of a ward-level dry waste collection centre (DWCC) in a city and supervise local movement of waste. Garbage that goes uncollected ends up in the landfill. If the latter becomes full, all players lose. The game requires players to win by using resources (money, manpower, data) strategically to build DWCCs across the city. The aim, Palavalli explains, is to help people understand the process and challenges of waste management in metros, and how they can help smoothen the process.

Another game, Made To Order, is centred around a garment factory and highlights how workers (especially women) in unorganised sectors navigate caste, class and gender discrimination at the workplace on a day-to-day basis. “Games are a way to shape policy discourse from an experiential position rather than a rhetorical position,” says Palavalli, who is working with government officials in Bengaluru and Chennai to devise games for mobility and urban planning issues respectively.

The data used in these games is collated from official, on-ground sources so that the play is consistent with reality. “Games are pedagogical tools that we design within certain theoretical frameworks to enable impact assessment. This makes it easier to create awareness and participate in the policy planning process,” Palavalli explains.

The board game culture of the West caught on in India a few years ago, with people going beyond Snakes and Ladders, Chess, Scrabble and Monopoly to play globally popular games like Dungeons and Dragons, Catan, Codenames and Pandemic. Their elaborate and intriguing plotlines ensured that these games went beyond child’s play and posed tough challenges that adults enjoyed solving. Board game cafes, communities and conventions sprung up across the country, especially in metros, to help people get together and experiment with tabletop plays sourced from different corners of the world.

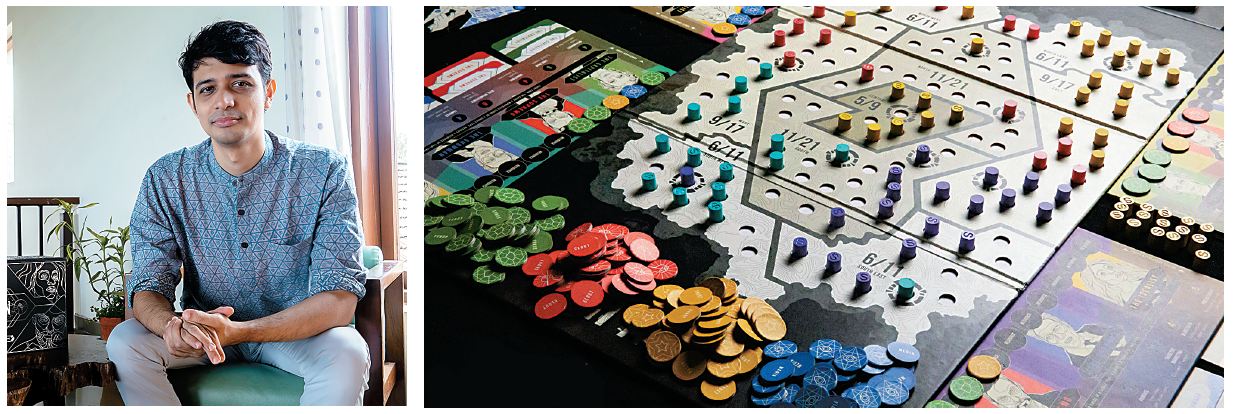

Game designer Prasad Sandbhor is working on two board games—one based on ecology and the other on startups

Game designer Prasad Sandbhor is working on two board games—one based on ecology and the other on startupsImage: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

This trend has resulted in games being designed specifically for the Indian market. A 2017 estimate by market research firm Euromonitor pegs the size of India’s board games and puzzles market at ₹330 crore. This is expected to grow to ₹400 crore in five years. Globally, the industry is valued at $20 billion, with a CAGR of 9 percent between 2017 and 2023, according to statistics portal Statista.

“There is a social isolation that people are experiencing in our tech saturated world,” says game developer Zain Memon. “Against this backdrop, board games have emerged to provide the perfect, face-to-face human bonding experience. More people are now hanging out together after work, after school, and catching up with their friends over a board game or two, sitting across each other in a room.”

A handful of game developers in India are therefore using this platform to create games that not only engage, but also educate. They are getting students, non-profits, government officials and researchers on the gaming table to spend anywhere between an hour and 10 in order to simplify complex issues, build awareness and enable productive dialogue.

Game developer Zain Memon raised money for Shasn on Kickstarter

Game developer Zain Memon raised money for Shasn on KickstarterMemon’s Shasn is one of them. It joins games like The Poll and Mantri Cards, which intend to help people understand how politicians tackle policy issues, examine their own beliefs and have a healthy political discussion. Launched in July, Shasn comes with four playable political campaigns—India 2020, USA 2020, Earth 2040 and Rome 40 BCE. Every campaign has 88 cards, each containing relevant policy questions like ‘Should the GST be abolished?’, ‘Should religious institutions be made to pay taxes?’, ‘Should the national anthem be mandatory in cinema halls?’, ‘Should caste and minority-based reservations be abolished?

“Our team met with several political scientists, theorists, policy-thinkers and influencers across all walks of life. To all of them, we posed a unifying question: What are the most urgent problems of our world? We have collated their answers, sifted through our own research and assessments and arrived at the policy questions in the final game,” says filmmaker Anand Gandhi, founder and CEO of the Memesys Culture Lab that produced Shasn.

The way a player answers these questions shapes the kind of politician she/he will become—capitalist, supremo, showman or idealist. Answers earn resources that help get votes. “The archetypes that we have selected dominate our political mainstream right now in various avatars, and to get a clearer idea of how to wield these beliefs productively, we must first put them under the microscope,” explains Gandhi. The four-player game also comes with 80 conspiracy and headline cards that deal with real-world election campaign challenges like rumours, fake news and public trust. Memon says they will release new versions of the game every year to update policy debates and developments.

Building Blocks

Most game creators in India do not pursue active marketing, instead reaching out to audiences through word of mouth, on-ground connections with their immediate community, and targeting sub-groups like social enterprises, non-profits, universities and corporates that are highly networked. Social media and ecommerce portals help them with visibility and accessibility, while crowdfunding sites like Wishberry and Kickstarter lower the barrier of entry for people trying to get a board game into the market. For instance, Shasn, which was listed on Kickstarter, was able to raise its budgetary requirement of $25,000 (approx. ₹17.6 lakh) in just over a day’s time. By the first week of August, it had raised $159,595 (approx. ₹1.12 crore) with about 10 days left in its month-long campaign. Around 21 percent of the contributors were from India, while about 46 percent were from the US. Board games earned nearly $180 million on Kickstarter in 2018.

“Anyone can develop a board game,” says designer Prasad Sandbhor. “Because the fundamentals are simple: Create rules around a basic concept and feedback mechanics that set a reaction to every action.”

That said, creating a good game, he explains, requires specialised skill and effort. “Designers must be on top of their subject matter; iterations must be open-ended for people to find their own interpretations while playing the game. Then there are also aesthetics that set the language and narrative. All this will determine whether people come back to play again and retain knowledge received out of the playing experience.”

Bengaluru-based Sandbhor is designing two culturally-relevant board games. The first, called Flocks, aims to create awareness about mixed species bird flocks. It is being developed pro bono in collaboration with Priti Bangal, a PhD student at the Centre for Ecological Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). The second is called The Founder, which intends to make startup entrepreneurs aware of the many challenges they are likely to face in the first three years of their business.

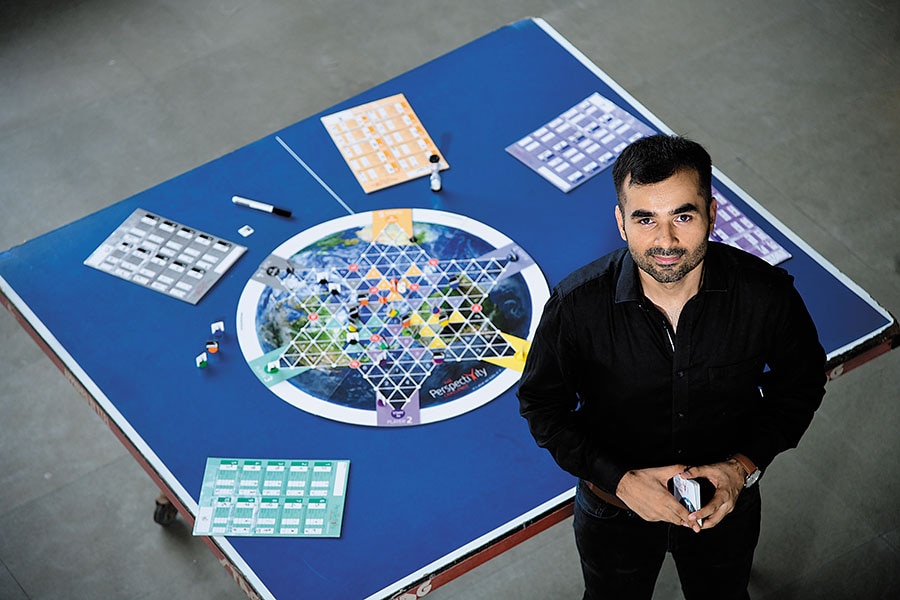

Anubhav Khanduja is the India head of Netherlands-headquartered non-profit Perspectivity. Their board games on climate change and human security are popular in the country

Anubhav Khanduja is the India head of Netherlands-headquartered non-profit Perspectivity. Their board games on climate change and human security are popular in the countryImage: Mayur D Bhatt for Forbes India

Commissioned by 8Infinity, a Pune-based startup co-founding and consulting firm, The Founder will offer players simulations of how intellectual, social and financial capital could be deployed in various sectors.

The challenges introduced in the game are in the form of economic uncertainties, macro-events or major policy changes, and micro-events or daily occupational hiccups.

“The board is divided into financial quarters and a sheet calculates capital flow through five levels spread across three years of an entrepreneurial journey,” explains Sreekar Channapragada, managing partner, 8Infinity.

The game, he says, cost up to ₹5 lakh from conceptualisation to development, and will be out by the end of the year. Initially, it will be made available to startup founders who collaborate with 8Infinity, apart from business schools and colleges. Referring to how the recent suicide of Café Coffee Day founder VG Siddhartha put the spotlight on the loneliness of an entrepreneur’s journey, Channapragada says a game like this will help businessmen identify the various “emotional rollercoasters” they could experience during their startup journey.

Funds versus Scale

While the money received for commissioned social impact board games depends on factors like the complexity, the subject matter and the time in which it has to be ready, most developers depend on grants, awards or fundraisers.

Anubhav Khanduja, India head of Netherlands-headquartered non-profit Perspectivity—whose social impact games on climate change and human security are popular in the country—says their priority audience comprises social enterprises, policy think-tanks and universities.

“The latter, especially, is a huge market opportunity in India, considering that Perspectivity’s games abroad are licensed or played by institutes like the London School of Economics, Oxford University, Wharton and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,” he says, explaining that annual licensed versions of these games cost around €1000 (approx. ₹79,000). “Prices are not likely to be localised in India until we gain minimum mass traction. We are working to create games for commercial usage and will get into production soon,” says Khanduja, who is pursuing an MBA at IIM-Ahmedabad and is popularising the game among students and faculty members.

Khanduja is also conducting facilitated sessions for social organisations and corporates like Wipro, Selco, Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and Teach for India, among others. While contracts and monetary terms for these sessions are directly negotiated by the companies with the Perspectivity headquarters, volunteers conducting the game receive between €250 (approx. ₹20,000) and €300 (approx. ₹24,000) per session. “Our corporate activity is limited by our capacity, but there is no denying that after educational institutions, corporate support is needed to provide stronger momentum to these games,” he says.

Jacob Mathew, design principal at Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, who leads an incubator at the institute and uses games for his work there, says while the social sector sees immediate value in board games, corporates look for tangible, quantifiable outputs. “It all depends on how you package and sell it. These games could be used for skill development, social responsibility and capacity building, functions that corporates care about. So instead of a sustainability tool, sell it as a strategy tool. Because the big currency is going to be in corporates.”

Palavalli of FoV, whose annual budget for developing games is between ₹80 lakh and ₹1 crore, says scale does not necessarily dictate impact. For instance, he says, the number of people who might play a game on disaster management will be just around 5,000. “But our studies have shown that if the response time of these 5,000 individuals improves even by 0.5 seconds, around ₹10 crore of resources could be saved on a yearly basis,” he adds. “Unfortunately, not many people in India fund the process to create systems. They only fund outcomes.”

The challenge, Palavalli says, is to ensure that people retain the knowledge received through the board game, for which they have to engage with it over a period of time. “Games are not a silver bullet that will change things overnight, but awareness about their benefits is increasing. If we work on things together over a period of time, something good will definitely come out of it.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)