India's aviation sector: The capacity conundrum

The robust air passenger traffic growth recorded in the country this year may well be a bubble as airlines have increased capacity, only to sell seats for a song

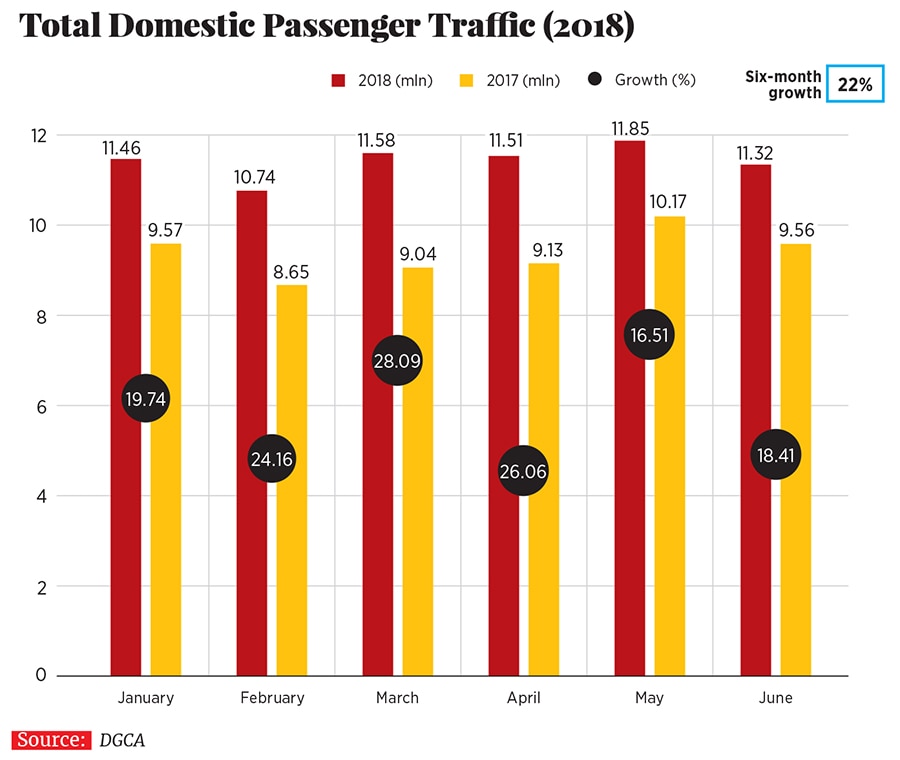

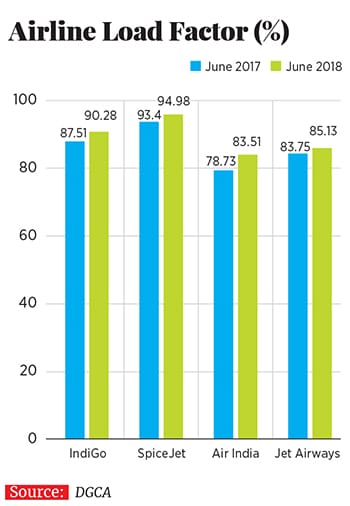

Domestic passenger traffic for the six months till June has grown by 22 percent from a year ago. All major airlines are flying at higher load factors

Domestic passenger traffic for the six months till June has grown by 22 percent from a year ago. All major airlines are flying at higher load factorsImage: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty images

By all appearances, India’s aviation sector is sitting pretty. A cursory look at data from the civil aviation regulator suggests that the country’s airlines are in cruise mode—domestic passenger traffic for the six months till June has grown by 22 percent from a year ago and all major airlines are flying at higher load factors (a measure of capacity utilisation) compared to last year.

However, appearances are often deceptive. Like retailers try to sell a perishable commodity at throwaway prices before it gets spoilt, unsold seats in airlines too have been going for a song. While this has elevated traffic and load factor figures, analysts say the numbers are an unsustainable aberration.

“Airfares are so low that we are stealing people out of buses and taxis at fares that simply don’t cover costs,” says Sanjiv Kapoor, chief strategy and commercial officer of the full-service airline Vistara. This means growth in the aviation market is being driven by excess seat capacity and low fares.

To put things in perspective, a one-way ticket on the high-traffic Bengaluru-Delhi route, booked 15 days in advance, starts at ₹3,530. In comparison, a three-tier AC fare on the Rajdhani Express on this route is ₹3,800, when booked two weeks prior to the travel date. “This is ridiculous considering it’s an over-two-hour-long flight,” says Devesh Agarwal, editor, Bangalore Aviation, an aviation news web portal. “The same thing happened in 2012 and the moment airlines increased fares, the market [passenger traffic] disappeared,” adds Agarwal. “It’s what is called profitless growth—passenger traffic is going up only because airfares are so low.”

The higher traffic and load factors recorded this year aren’t reflective of “healthy growth”, says Vistara’s Kapoor, an aviation veteran of 20 years. The rule of thumb in the industry, according to him, is that the natural growth rate of the market should be 1.5 times that of the country’s GDP growth. Given India’s GDP growth rate of over 7 percent, the aviation industry should ideally be clocking around 12 percent growth, as against the much higher 22 percent clocked in the January-June period.

The 10 percentage point difference between current growth and the so-called real growth, says Kapoor, is because of “artificial stimulation” of demand in the market and “unhealthy pricing” of air tickets. In a market beset with overcapacity and price-sensitive customers, combined with the fact that an airline seat is a perishable product, “airlines are tempted to get some revenue rather than no revenue from every seat”, adds Kapoor.

Consider the capacity addition of IndiGo, India’s largest airline by market share (41 percent). As of June this year, the airline operated a fleet of 169 aircraft, compared with 135 a year ago. The aircraft IndiGo added (34) is twice the fleet size of AirAsia India, the Indian arm of Malaysia’s low-cost airline AirAsia, and one-and-a-half times the fleet size of Vistara—a joint venture between Tata Sons and Singapore Airlines.

Another way of measuring the capacity growth is to look at IndiGo’s ASK (available seat kilometre—the number of seats available multiplied by the number of kilometres flown), which has increased by 18.4 percent, from 15.1 billion in June 2017 to 17.8 billion in June 2018. (The growth would have been higher if the airline was not forced to ground some of its newly inducted Airbus 320 neo aircraft on account of engine issues, which continue to persist.)

Yet the company’s RASK (revenue per available seat kilometre) was down to ₹3.70 from ₹3.82 a year ago, a sign of how low fares are affecting the bottomline. “The current revenue environment continues to remain weak particularly in the 0-15 day booking window,” Rahul Bhatia, co-founder and interim CEO of InterGlobe Aviation, which owns and operates the IndiGo airline, said during the company’s quarterly investor call last month. “We do not believe these fare levels are sustainable, especially given the increase in input costs,” he added.

If one were to extrapolate the financial health of the Indian aviation market based on the FY19 first quarter earnings of the three listed airline entities—IndiGo, SpiceJet and Jet Airways—the situation looks grim.

The impact of low fares on IndiGo’s June quarter profit was to the tune of ₹330 crore. Besides, the airline was impacted by a 54.4 percent rise in fuel costs as well as a foreign exchange loss of ₹246.1 crore, following the rupee’s fall against the dollar (currency fluctuations directly impact airlines by way of aircraft lease rentals). IndiGo reported a meagre profit of ₹27.8 crore in the quarter, compared to ₹811.1 crore a year ago.

SpiceJet, meanwhile, reported its first quarterly loss (₹38 crore) since December 2014, when the airline almost went bust. Besides a higher fuel bill of ₹812.44 crore and ₹44 crore in forex loss, the airline also had to set aside ₹63.5 crore as an exceptional item on account of the legal battle it’s fighting with its erstwhile promoter—the Chennai-based Sun Group.

Jet Airways has deferred announcing its first quarter financial results, saying its audit committee “did not recommend the financial results to the board for its approval, pending closure of certain matters”. This coupled with multiple media reports of the airline needing “urgent funding” for its operations is reminiscent of how things spiralled out of control for rival SpiceJet four years ago. Jet Airways reported a loss of ₹76.76 crore in fiscal 2018.

Recounting the turbulence of 2014, when aviation fuel prices peaked, hurting the profits of airlines, Kapoor, who was then the chief operating officer at SpiceJet, says, “At present, ATF [aviation turbine fuel] prices, in rupee terms, are about 10 percent less than what they were in 2014. So it [poor profitability despite ATF prices not peaking] is a bad situation.”

Worse still, says Kapoor, is that the average airfares at present are much lower than what they were in 2014. “Back then, airlines were keeping their fares quite high [closer to the date of travel]; a Delhi-Mumbai one-way ticket was [on average] ₹8,000, now it’s ₹3,000.” Reason: There wasn’t an overcapacity of seats in the market back then.

Today, new aircraft are being inducted by airlines and to fill the extra seats, fares are being suppressed. And in doing so, Kapoor says, “We are not able to maintain any pricing discipline closer to the date of travel and that is what is making the situation worse than what it was in 2014.”

Will domestic airlines cut back on capacity addition in a bid to return to a healthy price regime? Unlikely, it seems.

IndiGo will continue to take deliveries of its A320 neos and smaller turboprop ATR aircraft. The airline has projected a year-over-year capacity increase in terms of ASKs of 28 percent for the September quarter of the ongoing fiscal and a full-year capacity increase of 25 percent, which includes its international operations as well.

Greg Taylor, senior advisor at InterGlobe Aviation, while speaking during the company’s recent investor call said that IndiGo’s focus was firmly on long-term strategy and not on short-term woes as “India continues to be a very under-penetrated market with respect to air travel”.

More telling of IndiGo’s overwhelming control of the market was when Taylor said, “Although we are sitting here with fares and yields that we do not think are sustainable in the long run, we do think that with the cost that we have and the strong balance sheet, we are in a better position to sustain and do well in this environment than anybody else.”

IndiGo is definitely at a vantage point. “It is an employer of choice, it has majority slots at most airports, so even business travellers would fly IndiGo just because it has so many frequencies between any two cities,” says Vinamra Longani, a former cabin manager at UK-based Virgin Atlantic, who is currently heading operations for a BPO based out of Gurugram.

Simply put, if competitors don’t add capacity they won’t get decent airport slots, even at tier 2 and tier 3 airports where IndiGo now flies its ATR aircraft. “So [other] airlines have no choice but to keep growing,” says Longani.

SpiceJet has plans to induct 15 aircraft by December this year. “As we start inducting the new fuel-efficient B737 MAX and the Bombardier Q400, we will be able to significantly reduce our overall costs even as we aggressively expand our network both in India and overseas,” says Ajay Singh, chairman and managing director, SpiceJet, while announcing the airline’s June quarter results. Jet Airways, too, is adding around 11 B737 MAX aircraft to its fleet by the end of this fiscal.

The real problem though will be for smaller airlines such as AirAsia India. “They hardly have any presence at the metro airports; they only fly to tier 2 airports because there are no slots at the metro airports,” adds Longani. Says Agarwal of Bangalore Aviation, “It’s all about grabbing prime slots. They [IndiGo] are able to dictate terms and corner more resources.”

While IndiGo may have by far outpaced competition in capacity growth over the last year, which is what seems to be causing a lot of heartburn for the industry, the fact is that every airline in India has placed multi-billion dollar worth of aircraft orders. SpiceJet and Jet Airways have on order 205 and 225 next-generation Boeing aircraft, respectively.

“They [airlines] definitely need new generation aircraft. The question is where is the airside infrastructure [in India]? And is there actual demand?” asks Agarwal. “The only airline that I can see, which is sort of showing a kind of maturity and realism is Vistara. It has ordered a total of 50 A320s, which is a baby order,” adds Agarwal. In the last 12 months, Vistara has added about four A320 aircraft to its fleet. “We have measured our growth based on what we think the market can absorb,” says Kapoor.

Capacity rationalisation, according to Kapoor, can happen in one of three ways: Airlines need to dial back on their expansion, which is unlikely as each has committed aircraft orders; somebody goes out of business; or there is a merger.

“All over the world we have seen that these are the only three ways in which capacity can be rationalised,” says Kapoor. It’s anybody’s guess as to which of the three situations would finally play out in the Indian aviation market.