Info Edge: Getting the job done

Naukri.com has worked wonders for the company. But can its success be replicated at the its other ventures?

Image: Amit Verma

He helms an almost ₹20,000-crore (by market capitalisation) public company that has diligently churned out profits every quarter, for a decade, a rarity among home-grown internet businesses. That this has been achieved with a measly ₹7 crore in venture capital (VC) funding is an even bigger rarity in India, where chasing investors to clinch billion-dollar fundings almost every year is as much a part of a unicorn CEO’s job as running the office.

But ask Hitesh Oberoi, 46, chief executive and managing director at Info Edge, if the company’s cash counters were ringing right from the beginning, and he says, “At that time, nobody really understood how to make money.”

The time that Oberoi refers to is circa 2000, when he quit his job at Hindustan Unilever to launch Baachao.com, an online deals platform, with Sanjeev Bikhchandani, the founder and executive chairman of Info Edge. Bikhchandani had started the company in 1994, and had only one offering—Naukri.com, launched in 1997—when Oberoi joined him. This was an India where high speed internet was a pipe dream, and venture capital a novelty. The likes of MakeMyTrip, Indiaplaza and Contests2win, the early birds of India’s dotcom story, were beginning to take wings, but it wasn’t clear how long their flight would last.

The US markets, however, were a different story. The dotcom bubble was only growing bigger, with companies such as search engine eXcite, and grocery delivery startups Kozmo and Webvan. Bikhchandani and Oberoi could only hope that some of that enthusiasm would spill over to India as well.

Naukri and Baachao aimed to bring online a part of the classifieds ads of newspapers. A team of executives would spend their days rummaging through newspapers, spotting relevant ads, and posting them online. But there wasn’t much money to be made in the land of 55 lakh internet users. “Bachaao wasn’t making any money. In the three years since [Naukri’s] launch in 1997, we had gone from zero to ₹3 lakh a month, and nobody could even imagine how it would go to ₹30 lakh a month,” recalls Oberoi.

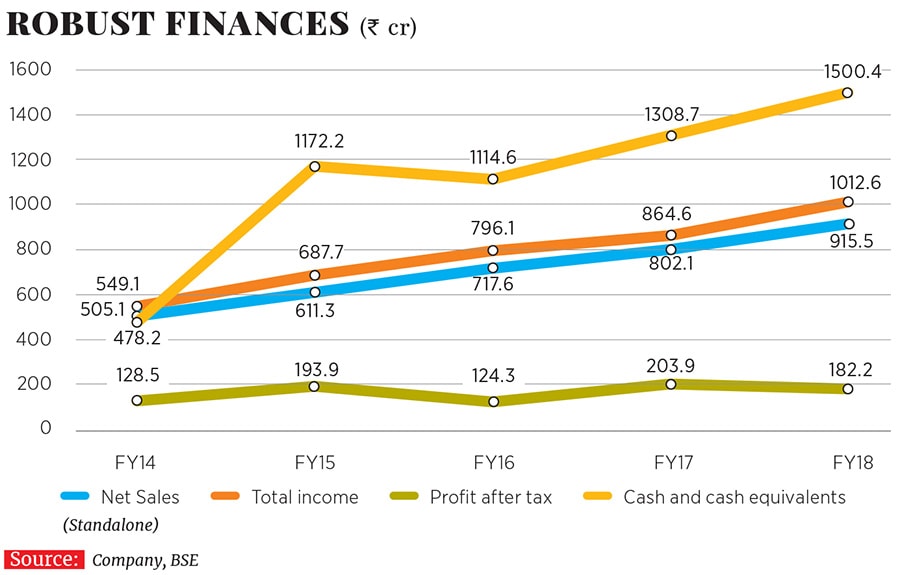

Today, Info Edge has business verticals in recruitment (Naukri), real estate (99Acres), matrimony (Jeevansathi) and education (Shiksha); in FY18, it posted ₹182.2 crore in profit after taxes on net sales of ₹915.5 crore. Its stock trades at a multiple of over 100 times earnings, far in excess of the 41 times the mid-cap index trades at.

Apart from its own verticals, the company has invested about ₹1,500 crore in 20-odd startups. Two among them, Zomato, where Info Edge has a 27 percent stake, and Policybazaar, where it has 13.5 percent, are unicorns (valued at more than $1 billion). Both can add significant heft to the firm’s balance sheet—cash and cash equivalents stand at ₹1,500 crore—once Info Edge sells the stake, adding to the optimism around the company in the bourses. The stock was up 15 percent in 2018 even as the broader market was down 20 percent.

“Overall, the business is in amazing shape because it generates good cash flows, which can be channelled into initial investments in companies to help them grow; they can then exit at the right time. Zomato and Policybazaar have grown significantly. These factors also contribute to Info Edge’s valuation,” says Milan Desai, analyst, information technology at IIFL Securities.

Info Egde, it seems, has mastered the maths of running online classifieds in India. Industry observers attribute this success to the fact that consumers don’t pay anything to use the platforms, except for Jeevansathi. From listings of jobs, real estate and education, Info Edge earns most of its revenue from businesses, advertisements, listing fees and subscription products. This is in sharp contrast to the likes of OLX and Quikr, where a consumer (individual or enterprise) has the option to buy a paid listing, but the vast majority of users don’t pay to have their products listed; consequently, they have also burnt through millions of dollars to acquire new consumers.

“You need people who are consistently willing to pay, and recruitment is a strong opportunity. Info Edge is not a customer-to-customer business, where companies are trying to handle fulfilment and get consumers to pay. That is the way of life for most classifieds companies, and that is how most of them are burning cash… figuring out how to make money from transactions,” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital Advisors, a venture debt firm.

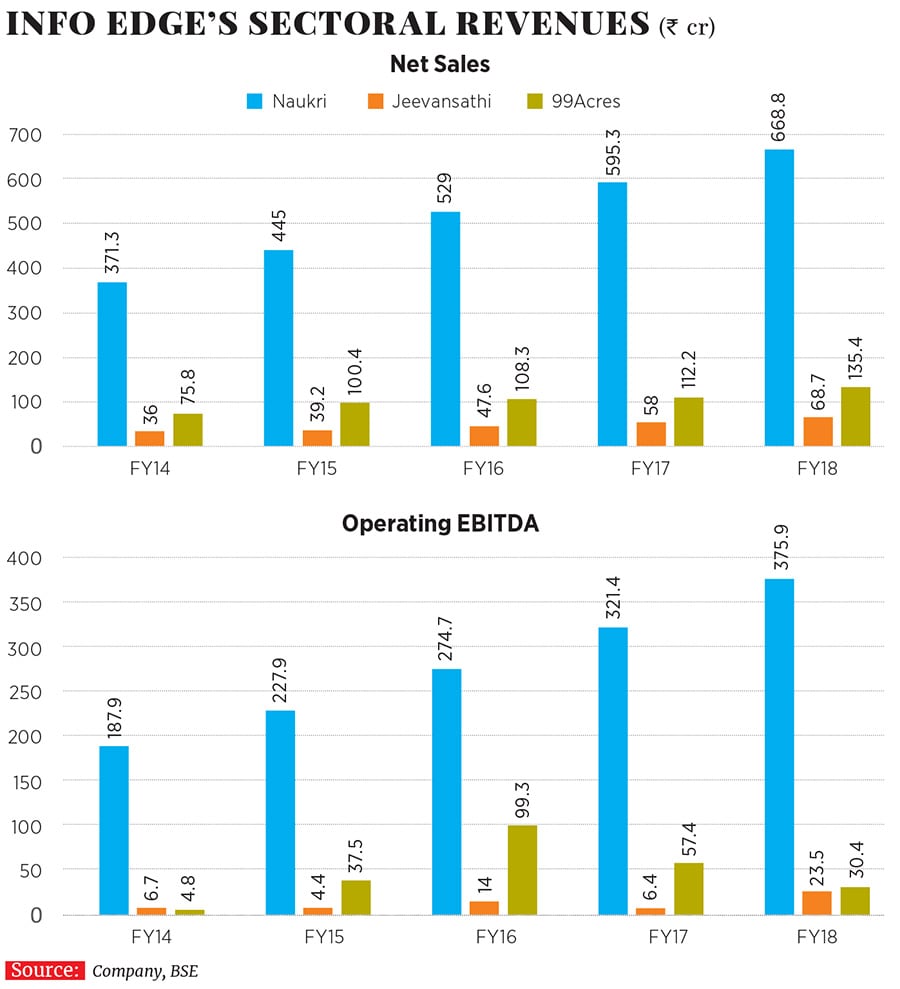

With 57 million resumes in its repository, Naukri is a market leader, ahead of home-grown rivals Shine or Timesjobs. The business accounted for ₹668.8 crore (73 percent) of Info Edge’s overall net sales in FY18, while operating Ebidta margins stood at 56 percent.

*****

But for the halcyon days to last, it is possibly time for Info Edge to reinvent the wheel, and not remain a one-trick pony.

“We have invested in 20 businesses outside, and have four businesses inside Info Edge, and only Naukri is generating cash. There may be 1,000 internet businesses in India, but only Naukri is generating cash,” grins Oberoi. Although this says a lot about Naukri, it also hints at a few causes for concern.

On the investment front, Info Edge bought a stake in Zomato in 2010 and in Policybazaar in 2013, and they have become its biggest successes. It hasn’t got as lucky again. None of its bets ever since have scaled such heights. In fact, in 2018, Info Edge wrote off ₹53 crore in startup investments and provisioned for another ₹133 crore. “We haven’t really measured the returns because we don’t look for exits. We want to be part of good businesses,” says Bikhchandani, 55. “Clearly, Zomato and Policybaazar have done extremely well for us. The likes of Happily Unmarried and Meritnation have also begun well.”

On the business front, while Naukri is at the top of its game, the other verticals, which were launched around the time Info Edge filed for an IPO in 2006, have barely borne fruit: 99Acres earned ₹135.4 crore in sales, while Matrimony.com raked in ₹68.4 crore in FY18. At an Ebitda level, both verticals together lost ₹54 crore. Shiksha, however, posted an Ebidta of ₹2.8 crore on revenues of ₹42.5 crore.

Unlike Naukri, which is head and shoulders above competition, 99Acres, Jeevansathi and Shiksha are still scrambling for leads over their rivals. With ₹87 crore in net sales in the first two quarters of FY19, 99Acres lags Magicbricks’ turnover of ₹103 crore. Jeevansathi significantly trails Matrimony and Shaadi. Matrimony, the segment leader, posted ₹308 crore in revenue in FY18, about ₹50 crore more than Jeevansathi’s cumulative revenue of about ₹260 crore for the last five fiscals. The company, says Oberoi, has ploughed in about $35 million in 99Acres and $10-15 million in Jeevansathi over a period of 10 years.

What did Info Edge get right with Naukri, which it could not with its other portals? “What they have done with Naukri, they haven’t cracked fully with others. It isn’t like they are not doing well, but they are not exceptional either. At every stage they have competitors, and that is why it becomes harder to build,” says Shivakumar Ramaswami, founder at investment bank IndigoEdge.

Naukri survived and thrived at a time when competition was low and, more importantly, capital was scarce. Burning cash to acquire consumers wasn’t common practice. But times have changed. Between 2013 and 2016, VC funding was abundantly available, triggering a mushrooming of players in the real estate sector, Info Edge’s biggest vertical after jobs. Backed by the likes of NewsCorp, SoftBank and Tiger Global Management, startups such as Proptiger, Commonfloor, Housing, Quikr, OLX, Indiahomes and Indiaproperty started giving 99Acres a tough fight.

“When money gets raised, people start advertising, giving services for free. We were under pressure, because till 2013-14 we were running a very tight ship. Till then the total investment in 99Acres was ₹25-30 crore,” says Oberoi.

The real estate market, too, has remained subdued for about half a decade now, first because of the 2008 economic slowdown, then demonetisation and then the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Real Estate Regulation and Development Act (Rera). Also, according to industry executives, Google and Facebook account for a significant portion of online advertisement spends in a vertical such as real estate.

For 99Acres, however, the silver lining is the fact that most of its competitors from a few years ago have either folded up, been sold at scrap value or reduced to a has-been as the euphoria of VC funding died down. “We are hopeful that 99Acres will get somewhere very quickly. All we need is a good market for real estate for two to three years,” says Oberoi.

For Jeevansathi and Shiksha, it is a work in progress. “Marriages are happening, but nothing is happening to our business because we are No. 3 nationally,” says Oberoi. “We did a smart thing there: We decided to exit the South, and focus instead on the Hindi-speaking belts. We are a strong No. 2 in the north and west, after Shaadi. As a strong No. 2, you have a chance, but as a weak No. 3 you don’t.” For Shiksha, the challenge is to grow faster. “We haven’t been able to figure out as yet as to how to make Shiksha a ₹500-crore business.”

*****

Oberoi’s strategies will be a test of whether he can repeat the success of Naukri.

In 2000, when he quit Unilever to join Info Edge, a fledgling internet company started by Bikhchandani, Oberoi had applied his learnings from the FMCG giant to steer Naukri past impending pitfalls.

What worked for Naukri is that the company deployed an army of on-ground salespeople to walk up to clients and pitch their products

What worked for Naukri is that the company deployed an army of on-ground salespeople to walk up to clients and pitch their products Image: Shutterstock

In 2000, when Naukri was still limping along, JobsAhead, a jobs portal founded in 1999 by Puneet Dalmia (now the managing director of Dalmia Bharat Ltd) and Alok Mittal (he runs Indifi Technologies), upped the ante by raising ₹33 crore from Chrys Capital. What followed wasn’t any different from what happens now. “JobsAhead was very aggressive. They built a good product, hired a lot of people, started doing job fairs, and even advertised on TV,” says Oberoi. “We were in two minds. Life was easy, life was good. If you take money, then you need to grow fast. But, when JobsAhead raised money, we were taken by surprise. We were also a little scared of what would happen to us. Eventually, we also decided to take money.”

In May 2000, Info Edge sold a 15 percent stake to ICICI Ventures for $1.7 million (about ₹7 crore), the only time it would ever raise money from a VC firm. (A 2014 QIP raised ₹750 crore.) Naukri, which barely managed to make ₹3 lakh a month, set itself the rather audacious goal of generating ₹22 crore in sales in five years. To counter JobsAhead, it spent ₹70 lakh in advertisements over the next couple of months, exhausting about one-fourth of the first tranche of ₹3 crore from ICICI Ventures. But, still, the needle didn’t move.

What followed next defied the basic tenets of building an internet business, which were characterised by asset light models and remote sales, as pursued by US peers Jobstreet and Stepstone. Naukri, instead, adopted the FMCG model of marketing and distribution, and deployed an army of on-ground salespeople. They recruited graduates from small colleges, paying them a fraction of what it would have to pay graduates from premium business schools, to walk up to prospective clients—recruiters and human resource managers—to pitch Naukri products.

The success of this model is proven by the fact that Info Edge has stuck to its guns ever since. At ₹393 crore in FY18, employee benefit expenses comprise about 60 percent of its overall expenses, followed by advertising and promotion costs, which, at ₹116 crore, account for 19 percent.

“They [the competitors] could not sell, or just didn’t have the sales network. They were all good products, but they could not go beyond the top 50 or 100 companies. They all exited between 2001 and 2004,” recalls Oberoi. “Had we not invested in a field sales force, and instead followed the Western philosophy, business wouldn’t have happened because the market needed people on the ground.”

While global peers withered in India, Naukri began to blossom. Oberoi says Naukri cruised to ₹47 crore in sales by fiscal 2004-05, double the initial target of ₹22 crore, riding on the back of a 400-strong sales team.

The threat from JobsAhead, however, continued to loom although in a different form. The firm was acquired by Monster, one of the biggest global online job portals in 2004. Monster, however, couldn’t upstage Naukri. “Once you have a dominant player, to displace it is very difficult, or the cost to do so is very high,” says Ramaswami of IndigoEdge. “We had warded off the Monster threat to a large extent but it was a strong No. 2. If we had a 45 percent market share, they had 35 percent. In information technology jobs, which was the biggest vertical, we were neck-and-neck.”

The race continued until the sub-prime crisis of 2008 hit US stocks. While Naukri felt the tremors of recession in India, Monster’s global business took a hit, and it was subsequently reduced to a pale shadow of its former self.

*****

Oberoi, however, is not resting on his laurels.

The plan is to transition Naukri from a job portal to a careers platform, replete with engaging content, apart from entering segments such as blue-collar and premium hiring, and strengthening its campus recruitment business. “All of these will play out in the next one year,” he says, but won’t elaborate.

“It isn’t much different with today’s startups,” says Murali, of Alteria Capital. “There are areas of stability, and areas where they are pushing for growth. For Info Edge, it is not so much of burn but investment from the balance sheet in high-risk or experimental situations. Recruitment is their core strength but with real estate and matrimony, there has to be significant investments ahead.”

For Naukri, and Info Edge, however, there is no looking back. And Oberoi would like to keep it that way. “We will do whatever it takes to win.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X