UC-RNT: Tightening the purse strings

Why Ratan Tata's $300-million fund with University of California, a prolific series B and C investor in some of India's most high-profile startups till recently, has stopped for a breather

Ratan Tata is one of the most prolific investors in Indian startups by deal volume;

Ratan Tata is one of the most prolific investors in Indian startups by deal volume;Image: Pradeep Gaur/ Mint via Getty images

It was 2014, a year of many firsts for India’s fledgling startup universe. Breakneck growth at any cost was the order of the day, effected by a battery of benevolent investors. Amid all the din, Flipkart, the consumer internet poster child, had already secured the bragging rights to two significant firsts—it became the first homegrown ecommerce company to clock $1 billion in gross sales and snare $1 billion in a single funding round.

Cross-country rival Snapdeal, engaged in an audacious land grab with Flipkart and Amazon, wasn’t far behind. While Flipkart founders Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal basked in the glory of accomplishing unprecedented business goals, Snapdeal’s Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal possibly met a life goal—an endorsement from Ratan Tata.

It wasn’t just a public acknowledgement of Snapdeal’s business, or a private audience with Tata, laced with words of wisdom. Snapdeal became the first Indian startup to raise money from the chairman of Tata Trusts. The money, ₹10 crore, was paltry for an ecommerce company shrouded in gargantuan losses and burning hundreds of crores of rupees every month to wrest market share from competitors. Tata’s money was not meant to bolster the war chest. It was a matter of sheer pride for an upstart such as Snapdeal.

Tata, says an entrepreneur who got a cheque from him, seemed “genuinely curious” about startups. This possibly explains why he bought tiny stakes—cheques from RNT Associates [‘N’ stands for Naval, Ratan Tata’s father], his investment firm, could be as low as ₹10 lakh, as was the case with online lingerie store Zivame—to test the waters. Many of them were “innovative and disruptive”, says the entrepreneur, but all of them were making losses, with profitability nowhere in sight, a sharp contrast to Tata Sons that churned billions of dollars in annual revenue, and made profits.

But that was the nature of the beast and Tata was willing to take a stab. It wasn’t long before Tata stepped up his game. In about two years from writing his first cheque to a startup, Tata teamed up with the University of California (UC) to float an evergreen fund, with a $300 million initial corpus. “UC was the limited partner and RNT Associates was the general partner, with an option for co-investments,” says a venture capital (VC) executive.

Setting up UC-RNT was a welcome move. Growth capital for Indian startups was scarce and largely a stranglehold of global investors such as SoftBank, Tiger Global Management or Naspers among others, apart from a few strategic investors.

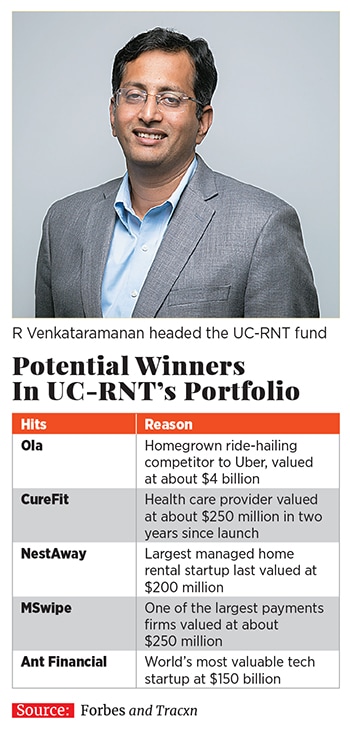

UC-RNT started on a high. The fund was headed by R Venkataramanan, former executive assistant to Tata and a managing trustee at Tata Sons. Tim Recker, managing director, private equity and real assets, at the University of California Regents, represented the university. The team also comprised Natarajan Ranganathan, former chief financial officer at Helion Ventures, Mathias Imbach, a former executive at Bain & Company, and Mayank Singhal, a former Temasek executive.

According to multiple VC executives, the fund invested in at least 10 companies of varying magnitude—unicorns such as Ola, and China’s Ant Financial (Alibaba’s payment arm), those valued at a few hundred millions, including NestAway, LivSpace and MSwipe, as well as early stage ones like Axio Biosolutions and YourStory.

“They emerged as a good series B and C investor. They had good deal flow and people wanted to go to them and take their money,” says a second VC executive.

*****

No new investments

“They were good till the point they were active,” he says. “I got in touch with them around June and was told that they aren’t making any new investments.”

According to five VC executives, UC-RNT has hit a roadblock. Recker, Imbach and Singhal have stepped down. Recker is now the chief investment officer and treasurer for James Irvine Foundation, while Imbach is the founding partner and chief executive, Singapore, at Sygnum. Ranganathan is managing the fund’s portfolio. The firm has almost exhausted its initial corpus—the rest has been earmarked for follow-on investments in its existing portfolio—and is unlikely to top up the fund.

“There are a lot of moving pieces here. Plans may change, but they will need to hire a new team and get things moving before raising a second fund,” says a person aware of the developments. Venkataramanan did not respond to an email from Forbes India seeking comment.

The fissures first appeared around March, when Ranganathan turned up for a few board meetings instead of Venkataramanan, Imbach or Singhal. “It is a little unusual for a CFO of a fund to attend board meetings. We guessed something may not be right, but there was no official communication,” says the second VC executive.

It was a time when key stakeholders in the fund were caught in rough weather. Cyrus Mistry was ousted as Tata Sons chairman two years ago. Much of Tata and Venkataramanan’s time was spent in putting the house back in order. In May 2018, the CBI filed an FIR against AirAsia India, a joint venture between the Tatas (51 percent stake) and Malaysia’s AirAsia Berhad (49 percent), some of the company’s key executives, group CEO of Air Asia, Tony Fernandes, and deputy group CEO Tharumalingam Kanagalingam. The charges were of bribing government officials for an international flying permit for AirAsia India, though the airline did not meet the 5/20 requirement, which mandates five years of operational track record and a minimum of 20 aircraft to bag international flying permits. Venkataramanan, who sat on the AirAsia India board, was also named in the report. “Venkataramanan was a key decision maker in the fund. But with the AirAsia issue, the focus was lost,” says the VC executive.

Things weren’t rosy at the investment office of the University of California, which manages about $120 billion. Jagdeep Singh Bachher, the chief investment officer there, had come under heavy criticism as a bevy of senior executives, including some hired by Bachher, quit the firm. The executives, claims a September report by Institutional Investors, were rankled by alleged false promises made by Bachher and certain practices that they did not relate to.

An email sent to the office of the chief investment officer did not elicit a response.

*****

Prolific in the past

For Tata, a lot happened on the startup front in the two years since he invested in Snapdeal and launched UC-RNT. He emerged as one of the most prolific investors in startups by deal volume. By the end of 2017, Tata had backed at least 40 startups in his personal capacity, including the likes of Ola, Paytm, Xiaomi, Lenskart, Bluestone, NestAway and UrbanClap.

Tata, it seemed, had aced the art of private investments. He had joined VC firms Jungle Ventures, Kalaari Capital and Chiratae Ventures (earlier called IDG Ventures India) as an advisor. This apart, RNT Associates invested in SeedPlus, an early stage fund backed by Jungle Ventures and Accel Partners among others. At least 15 of his personal investments were startups backed by either of the four firms.

“He gave a lot of time to the founders… the startups weren’t just meeting his investment managers, but Tata himself, which was a big thing. There was a personal touch unlike some of the family offices, which are run more by professional people,” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital, a venture debt firm. “He is a great name to have on your side. It is not about money but credibility.”

A couple of years ago, marquee funds such as Accel Partners, Matrix Partners, Chiratae Ventures, Kalaari Capital, Nexus Venture Partners, Sequoia Capital or SAIF Partners were largely focussed on early stage deals. They have all raised large funds since, which has given them the heft to write big cheques. A few growth funds such as A91 Capital have also surfaced in the recent past.

“Growth capital is a huge opportunity because there haven’t been too many players. India doesn’t have a robust series B/C capital pool. That is why early stage funds are upping their fund size. The likes of Tiger Global Management, Naspers or SoftBank will come in for high growth businesses, but what about the rest? There is a great opportunity for funds to take over the space,” says Rutvik Doshi, managing director at Inventus Capital India.

UC-RNT isn’t looking to exit any of its investments. In fact, some of its bets are poised to deliver good returns. For instance, CureFit, the second venture of Myntra co-founder Mukesh Bansal, seems to be on steroids. It counts IDG Ventures, Kalaari Capital and Accel Partners among others as investors. UC-RNT’s cumulative ₹45.2 crore investment in the firm, where it holds 5.3 percent, was worth about ₹79 crore until August, according to Tracxn, a startup tracker. Similarly, payments firm MSwipe, where it held a 2.8 percent stake until December 2017, is growing fast. NestAway, a managed home rental startup where UC-RNT held a 9.7 percent stake until July 2018, is a category leader and is in talks to raise more than $100 million in fresh funds at a valuation much higher than the $200 million it last commanded.

“The situation wasn’t such that their investments went wrong. Also, with UC-RNT, it wasn’t like they blindly followed IDG or Kalaari’s cue. Things may have been different had the team stayed. Also, had all been well with the UC team in the US. But these things are true for any other fund,” says the second VC executive quoted earlier.

However, a revival cannot be ruled out, especially, with Tata’s legacy of scripting turnarounds.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)