Rema Rajeshwari: The good cop

With anti-misinformation campaigns through storytelling and cultural performances, IPS officer Rema Rajeshwari is effectively tackling fake news in India's low-literacy regions

Rema Rajeshwari, first woman IPS officer from her home district in Kerala’s Idukki

Rema Rajeshwari, first woman IPS officer from her home district in Kerala’s Idukki

Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

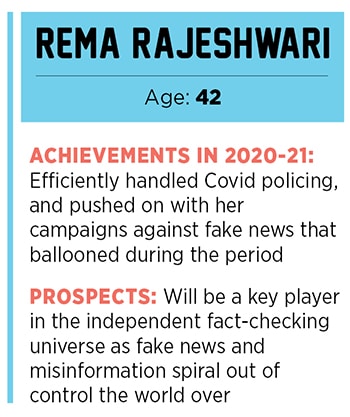

Before she became an IPS, Rema Rajeshwari did a Master’s in computer science. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the 42-year-old cop, the first woman IPS officer from her home district in Kerala’s Idukki, would often weave her passion into her profession. “I have a very strong academic interest in new-age crimes. And since the 2016 US elections, I have been following how misinformation has become a tool for influence operations,” says Rajeshwari.

Yet, in 2018, when Rajeshwari, then the district police chief of Telangana’s Jogulamba Gadwal region, received reports of villagers ganging up and attacking strangers “it didn’t occur to me that the malaise that had exploded with the US elections would trickle down to a backward, low-literacy district in Telangana”. Gadwal had a history of factional political violence, hence occasional brutalities weren’t unheard of, but her beat officers pointed the finger elsewhere. “They found two WhatsApp videos doing the rounds and spreading rumours of a kidnapping and an organ harvesting gang on the prowl,” says Rajeshwari. The digital gossip blew up into a law and order problem.

But it wasn’t one to be resolved by the books—no patrolling was ever going to be as fast and fuss-free as forwarding a message on social media. So, Rajeshwari launched a community outreach programme through which police officers went door-to-door to educate villagers on malicious fakes, and roped in local performers, village seniors as well as self-help groups to perform skits to highlight the message. In 2019, she was transferred to the communally-sensitive Mahabubnagar district where, too, she got her officers to propagate social messages through storytelling. But, in March 2020, Covid struck and Rajeswari had to withdraw her troops from the field.

“The first few months were hectic and my force was extremely stretched,” says Rajeshwari. “We were focusing on contact tracing, enforcing lockdowns, transferring patients from homes to hospitals, extending support to health care workers and taking care of essential supply management.” As the migrant crisis unfurled, workers from nearby Hyderabad began to stream along National Highway 44 that goes right through Mahabubnagar, heading towards Karnataka, Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh. “We rescued families that were looking to walk till Kanpur,” says Rajeshwari. “We established shelters, facilitated the setting up of Centre’s food bank on the highway for the migrant workers, arranged special trains and protected them from locals who were scared that they were carrying the virus along.” Rajeshwari also oragnised mobile safety teams for victims of domestic abuse, which was emerging as a shadow pandemic.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

In the meanwhile, fake news was also ballooning into a silent epidemic—migrant labourers were attacked for being “superspreaders”, so were people from the Northeast for being “Chinese” (among whom

In the meanwhile, fake news was also ballooning into a silent epidemic—migrant labourers were attacked for being “superspreaders”, so were people from the Northeast for being “Chinese” (among whom