Local Heat On Global Warming

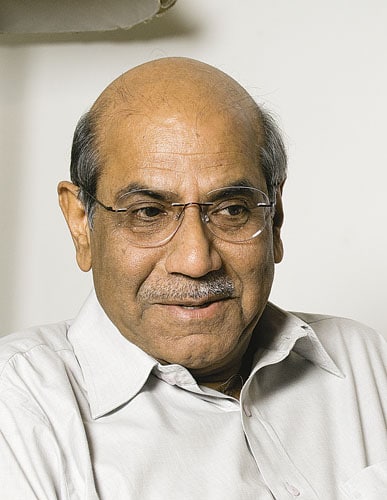

Special envoy for climate change Shyam Saran tells Forbes India the world's expectations from India with regards to global warming are unrealistic

Name:Shyam Saran

Title: Special Envoy to the Prime Minister of India on climate change

Age: 63

Qualification: Indian Foreign Service officer, 1970 batch

Work Experience: He was India’s ambassador in Nepal, Indonesia and Myanmar, High Commissioner in Mauritius, joint secretary at the Prime Minister’s Office, and foreign secretary.

Hobbies: Reading and travelling.

The EU and US have held their emissions at the 1960s level for the last 15 years but India’s emissions have increased by almost 250 percent...

If you wish to take 1960s as the base period, developed country emissions have climbed from about 8 billion tonnes of CO2 to 13 billion in 2004. During the same period, developing countries including India, have gone from about 1 billion tonnes to about 9 billion tonnes. India’s share of this is only 1.3 billion tonnes. Therefore, to hide behind percentage increases, ignoring what the base emissions figure is for the categories of developed and developing countries respectively, is designed to mislead. Our [India’s] current emissions constitute about 4 percent of the global total despite our having a billion-plus population. Our per capita emissions are at 1.2 tonnes. The US, by contrast, is responsible for over 21 percent of global emissions and its per capita emissions are 21 tonnes.

If India decides to reduce emission levels by 50 percent (compared to 1990) by 2050, how much will it cost?

It is important to clarify here that there is an existing, legally binding legal instrument called the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCC], which imposes a legal obligation only on developed countries to undertake emission reductions. Developing countries, too, should follow a path of sustainable development, but in their case, the incremental cost of any mitigation action they undertake, must be fully compensated by transfers of both financial and technological resources. Your query about costs in the hypothetical case India does undertake emission reductions, would require detailed estimation, but it would be fair to say that the costs would run into hundred of billions, if not trillions of dollars.

Does the manner in which India moved to a non-CFC economy hold any lesson for today’s climate change issue?

The lesson to be drawn is that there should be effective arrangements for technology transfer and adequate funding available.

Why is the West wary of passing on emission reduction technologies to the developing world?

We are not asking the West to share anything with us. What we are saying is that the developed countries should deliver on the commitments they have solemnly assumed in the UNFCCC. We should also look at another aspect of the issue of technology. If climate change is as urgent and serious a challenge as we say it is, then does it not make sense for us to create a global mechanism through which existing climate friendly technologies could be disseminated as rapidly and as widely as possible?

What are your expectations from the Copenhagen Summit?

It should be comprehensive in that it should cover all the issues mandated by the Bali Action Plan that is, mitigation, adaptation, technology and finance. It must be balanced in the sense that each of these issues are of similar priority.

And, the outcome must be equitable and fair. We cannot set a global goal without, at the same time, spelling out how the burden of reaching that goal is to be shared among developed and developing countries.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)