How escalating climate events threatens food security across the globe

Floods, droughts, cyclones, others, have devastated global food systems in the era of climate change. The world needs to come together to address these emergencies that threaten the planet

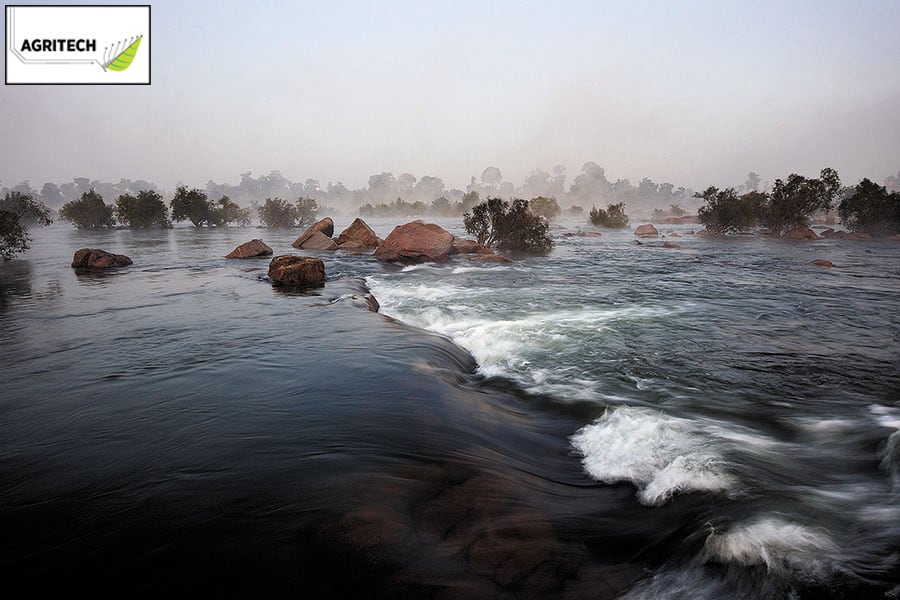

In 2021, heavy rainfall, flooding of rivers and overflowing dams killed 24 in Madhya Pradesh. In 2022, in another part of the state, drought reduced the production of rice crops to 10 million tonnes lesser than what it was the year before

Image: Chris L Jones / Dindia

In 2021, heavy rainfall, flooding of rivers and overflowing dams killed 24 in Madhya Pradesh. In 2022, in another part of the state, drought reduced the production of rice crops to 10 million tonnes lesser than what it was the year before

Image: Chris L Jones / Dindia

On World Water Day on March 22, 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the interlinking of the Ken and Betwa Rivers between Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh (UP) in a 231-km-long canal. The Ken-Betwa project was the first of the interlinking of rivers proposed in the National Perspective Plan (NPP) by the government, to provide irrigation to 1 million hectares of agricultural land and drinking water to 6.2 million people.

As important as water, weather and climate are equally critical to food production. However, escalating climate events—floods and landslides, heatwaves and drought, cyclone events and others—have devastated food systems in today’s world of climate change.

Environment, like agriculture, is a pillar on which human civilisation and our very existence depends and these two are inextricably intertwined. Our world’s emergencies have to be addressed together.

The interlinking of rivers is set to cause irreversible damage to the environment through the destruction of biodiverse forests in the Panna Tiger Reserve and Ken Gharial Sanctuary. The Ken-Betwa project alone (the first among 30 proposed interlinking projects) may submerge 6,197 hectares of eco-sensitive forests and destroy irreplaceable wildlife habitats. Preserving natural forests is key to limiting climate change and mitigating the reality of damage caused by climate events to agriculture.

In 2021, heavy rainfall, flooding of rivers and overflowing dams killed 24 people in Madhya Pradesh. The following year, in another part of the state, another climate event—drought—reduced the production of rice crops to about 10 million tonnes less than 2021.