India is luxury's next frontier

Like good wine, India's luxury market is maturing slowly but surely. As Indians spend on the finer things in life, the luxury market may touch $14 billion in 2016

Decisions, decisions, decisions: The Indian consumer has so many to make. If the buying bug hits, whether for a bag, a watch, a car or to host that lavish wedding or take a bespoke vacation, the range of options available is mind-boggling. Walk around Mumbai’s Palladium or Delhi’s Emporio or Bengaluru’s UB City malls and you get the clear and unmistakable sense that India as a luxury destination has arrived.

The diffidence is reducing too. First-time shoppers who earlier restricted themselves to window-shopping now step into stores. A few have bought that first luxury item—the pair of Diesel jeans or the Louis Vuitton bag. It’s an important mindset change, one that leaves little doubt that they will keep coming back for more in the years to come. After all, the additional benefits cannot be understated: At parties and office conversations, they’ll let it slip that they bought that fancy watch.

Most significantly, these habits have begun to set in.

Now, over to the luxe retailers: The purveyors of our high-life dreams. They’ve spent the last two years consolidating and gradually expanding in India. They broadened and deepened the scope of what they sell. And as they’ve gotten to know the Indian buyer better, the marketing tactics—not the products themselves—have been tweaked. Home delivery of luxury goods anyone? Yes, that’s also begun to happen.

It’s no wonder then that India is universally acknowledged as luxury’s last remaining large frontier market. Sure the market has taken a while to take off. India is roughly where China was in 2003, after which sales in the Middle Kingdom took off. According to a report prepared by KPMG for the India Luxury Summit 2014, the Indian luxury market is expected to grow at 18 percent annually to reach $14 billion in 2016.

The luxury market in India is at least a decade behind China, say experts. However, at the very least, Indians are now getting comfortable with the idea of spending on the finer things in life, they add. Sample this: Mumbai, home to the largest section of India’s billionaires, has over 500 apartments in the Rs 40-50 crore price bracket (a total of around Rs 25,000 crore) slated to be completed in the next three years. In other cities like Delhi and Bengaluru, the ticket sizes are smaller but the homes are no less luxurious. Stories of developers flying to Italy to select kitchen and bathroom fixtures are not unheard of. The apartments come equipped with concierge services, panoramic views and the finest spas. As Vikas Oberoi, whose Oberoi Realty is building Three Sixty West in Mumbai’s midtown Worli, says, “These are developments our country has never seen before and people have learned to spend on the finer things in life.”

The Opportunity

Let’s look at the opportunity first. Who are the buyers for the luxury goods, a category of products that is expected to generate revenues of $14 billion in the next year or so? KPMG divides them into three types: First, the HENRYs, or High Earning But Not Rich Yet consumers. This group comprises, typically, young status-conscious professionals who are the chief target audience of any luxury brand. They help spread the message of, and popularise, the brand. They can potentially make or break a brand. Over time, they can prove extremely loyal to a brand.

Next are the ‘windfall’ consumers who witness a sudden change in their lifestyle due to an unexpected gain in wealth. Usually this improvement in circumstance is from the sale of land or property and the resultant wealth may or may not prove to be sustainable. The beneficiaries also may or may not have access to luxury goods. These consumers are usually not on the top of luxury brand marketers’ lists and can prove to be fickle consumers. However, in certain pockets of the country, Gurgaon for instance, they have accounted for a large percentage of luxury car sales.

Then, there are the consumers from wealthy industrial families as well as C-suite executives. These are discerning buyers who are well-travelled and well-versed with the latest luxury trends. They know what they want but are also willing to try out new products. Think expensive ties and cuff links for men and shoes and bags for women. They are the most important customers for luxury marketers: They have real spending power, point out observers.

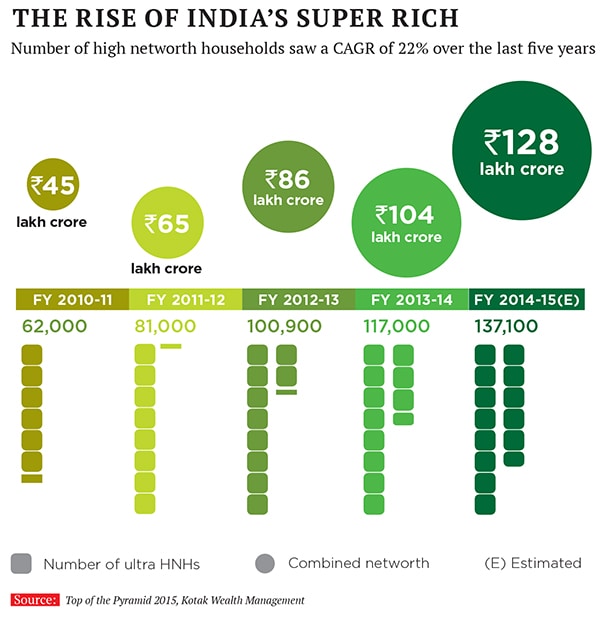

The numbers are by no means small. The three groups comprise a total of 1,37,000 households in India according to Top of the Pyramid 2015, a report prepared by Kotak Wealth Management. Kotak defines high networth households as those that have a net wealth of Rs 10 crore. The growth in this category has been impressive.

In 2010, these households numbered 62,000. From the present 1,37,000, they are slated to increase to 3,48,000 by 2020. The rise over the years has been consistent and broad-based according to Kotak. And it would appear that it is only a matter of time before the opportunity reaches an inflection point.

The Present Road

Darshan Mehta, chief executive of Reliance Brands (which is part of Reliance Industries, owners of Network 18, which publishes Forbes India), talks about the four stages of evolution of a market for luxury goods. “First, there are the counterfeits and fakes. Parts of India and China are still in this phase with people wearing knockoffs of luxury watches or buying knockoffs of expensive bags as they can’t afford the real thing,” he says.

The second stage is that of flaunting luxury goods, Mehta points out. And some Indians are prone to doing this. Tales of rich Indian housewives never repeating a bag to parties are the stuff of legends.

In the third stage, brands begin to assimilate into the culture. So there might be a day when Armani starts selling sherwanis or even safari suits!

Fourth is when luxury goods are considered a turn off. At present, this happens in parts of Japan and western Europe, and, even within this, among families that have been wealthy for generations.

For now, luxury brands in India are reaping a steady harvest. They are also learning to adapt to the Indian consumer. In Diesel, for instance, store managers have been empowered to boost sales by tapping into loyal customers. About a year ago, Deval Shah, business head at Reliance Brands, realised that there was a market for buyers in smaller cities who found it cumbersome to visit stores in larger cities: Diesel is available across 12 stores in seven cities. As a result, the home shopping service was launched, and in just a year, 14 percent of Diesel’s sales emerge out of this platform, the company says. “We try to create an in-store in the customer’s drawing room,” says Anshuman Bhardwaj, regional head for Reliance Brands. Store employees chart out a route. In Gujarat, they would visit 8-10 cities over the course of 15 days and come back with Rs 1 crore in sales.

A Diesel employee would also carry adjacent, but not competing, products like Brooks Brothers, which is also marketed in India by Reliance Brands. They have sold products in cities as diverse as Agartala (Tripura), Bathinda (Punjab) and Imphal (Manipur). While not all brands find it worthwhile to get into home sales, they keenly await the opening up of more quality retail space in the country. A number of upscale malls are expected to open in the next 18 months. “For now, the expansion is coming in the below ‘bridge-to-luxury segment’,” says Mehta. He defines this as brands that sell apparel for below Rs 10,000 a piece. A steady rupee—which has traded between Rs 60 and Rs 65 to the dollar—has also helped as has its appreciation against the euro since a substantial portion of luxury goods are imported from Europe.

In some cases, brands have gone the extra mile to cater to the customer’s pocket. BMW launched the 1 series at a price of Rs 20.9 lakh, which is at par with the pricing of some non-luxury brand carmakers.

Changes and the Slowdown

While most luxury watchers expect India to reach an inflection point soon, some caution that the Indian market could grow a lot differently.

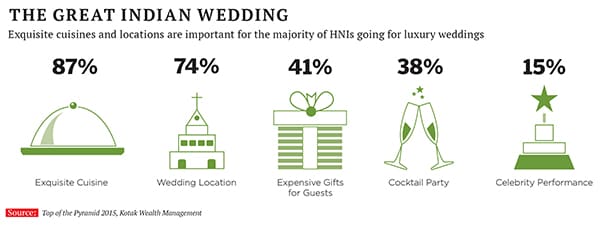

Radha Chadha, an independent luxury commentator and author of The Cult of the Luxury Brand, talks about how Indians are spending more on luxury weddings. And though the spend on luxury apparel is high, it is equally towards Indian wear as it is on western brands. “I see a larger propensity for spending on Indian clothing than on western clothing, especially among women,” says Chadha.

Homegrown labels of Tarun Tahiliani, Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Ritu Kumar have reported brisk growth, albeit from a small base. Then there are Indian brands like Forest Essentials that sell ayurvedic beauty products: The brand established itself so successfully as premium that Estee Lauder bought a 20 percent stake in the company in 2008.

Despite the growth of homespun labels, India is also still some time away from the ‘democratisation of luxury’—where a large number of people own at least one luxury item. “In countries like Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea, it is not unusual to find secretaries that have a Louis Vuitton or Prada bag,” says Chadha. In these markets, middle class consumers account for a larger percentage of luxury spend, as compared to the rich.

If India has to rise quickly as a luxury market for, say Western clothing brands, middle class consumers must start spending more. According to Chadha, this is the result of both lower income levels as well as an unprepared mindset.

Then there is the crackdown on black money that has resulted in a growing fear of being seen in a luxury mall, points out Darshan Mehta. This has been particularly pronounced in Delhi where visitors to DLF’s Emporio Mall have dropped. Long-time customers now prefer to take delivery only in their homes. They insist that their names and mobile phone numbers be erased from the invoice. And they also request for large value bills to be split below Rs 50,000 so as to not have to disclose their PAN numbers.

In 2013, the crackdown on gifting in China had sent luxury goods sales falling by 20 percent. While that is unlikely to happen in India, a clean-up on black money is a bitter-sweet pill for luxury retailers.

The slowing real estate market in the country has also dampened sentiment. People who don’t feel wealthy on paper are less likely to spend—this is particularly pronounced in north India, says Mehta.

Still, these are all small bumps in a road that is paved with riches. India is on track to become a $10 trillion economy in the next 10 years—the same size as China is today.

Just the prospect of that size and heft has luxury goods makers salivating—both at the magnitude as well as at the diversity. India is also among the last markets to mature that holds such immense potential. Call it The Final Frontier, if you will: One that all brands worth their promise are keen to conquer.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)