The Twitter-TV Nexus In India

While the scale of multi-screen engagement is still limited, its impact has not been lost on broadcasters and advertisers alike

Last week, the desi version of The Bachelorette went on air on Star India’s Life OK channel. Even idiot box atheists got the news—via their Twitter feed. For instance, during the telecast, and even prior to that, this writer’s timeline too was flooded with #TheBacheloretteIndia tweets; some were hashtag-ed #MallikaSherawat.

From Sherawat’s attire and attitude to her suitors’ intentions and behaviour, from conjecture about her fees to arguments on the futility of dating shows, the micro-blogging site was abuzz. It wasn’t all flattering, of course. For instance, one tweet read: “When something is so bad you’re cringing but can’t help but watch anyway.” And another: “Everyone demeaning her... How much did she get paid for the show to get insulted?”

Before you jump to conclusions, this Twitter hullabaloo isn’t a Sherawat-led aberration. It is, in fact, becoming the norm to follow a show as much on the “second screen” as on your television set.

In the past two years, TV shows (especially in the genre of reality and sports) have strategically generated massive chatter on social media platforms, particularly on Twitter. In some cases, this has translated into an increase in viewership for channels. In others, it has helped shows widen their reach and visibility.

This “multi-screen” experience that content providers are attempting to offer has given rise to the concept of ‘social TV’.

Simply put, social TV is where people live-tweet about the television programmes they are watching, sometimes managing to pull in new viewers, making TV-viewing a real-time group experience. In other words, the “second screen” (Twitter) becomes an ally and a “force-multiplier” for the first screen (TV).

Twitter has been projecting this parallel engagement as the next big thing in entertainment. The West, particularly the US, has become a willing participant in this new wave, but India, while showing intent over the last couple of years, is still at a fledgling state. “There is a significant potential for social TV in India,” says Jehil Thakkar, head – media & entertainment, KPMG India. “We are a significant source of content for Twitter but revenue-wise, we don’t even generate half of what Manhattan does.”

But, all the stakeholders agree that a start has been made.

India’s Twitter Tale

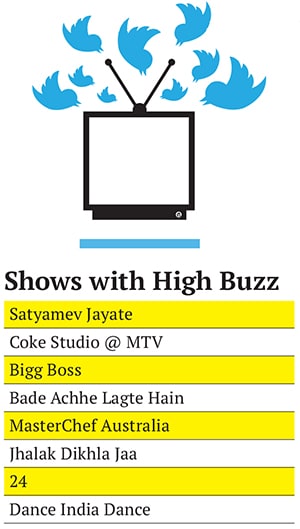

Star Plus’s Satyamev Jayate, Sony’s Bade Achhe Lagte Hain, Colors’s Bigg Boss, Star World’s MasterChef Australia and MTV’s Coke Studio @ MTV have been the biggest buzz-generators. And, quite often, tweet-conversations have compelled non-viewers to turn on their TV sets—out of interest or because of the need to ‘belong’ and participate in the chatter. Sometimes also out of sheer curiosity (and, perhaps, voyeurism) as in the case of Bade Achhe Lagte Hain, the rare fiction show that went viral on Twitter when its protagonists made love on national television.

Mostly, though, it is the non-fiction variety of TV programming that has struck a chord with the Twitterverse. Lalit Bhagia, former vice president of new media at Star India, recalls Twitter’s impact on Satyamev Jayate, the network’s flagship show on social issues that aired in 2012. “We just saw it grow and become massive as the season progressed. We went to advertisers and told them that it’s not just about the eyeballs [on TV] but also the engagement [on Twitter],” says Bhagia.

The show generated nearly 6 lakh tweets during its 14-episode first season (most of it live during the one-and-half hour of telecast) and went on to become one of the most watched and digitally visible properties of the channel.

Star India made another splash before the launch of Mahabharat a month ago. It bought trends for two days and ensured #AajKaMahabharat stayed on top of Twitter’s chatter charts. According to a source at a rival channel, Star reportedly paid Rs 30 crore for this partnership with the site. However, this couldn’t be confirmed with them.

Viacom 18-owned MTV India, known for its edgy content and a young target audience (the ideal demographic for Twitter), clocked a large number of tweets with its fusion music show Coke Studio. Twitter activity peaked during the AR Rahman episode on Independence Day with more than 1,000 tweets hashtag-ed #CokeStudioatMTV in an hour, and thousands more generated through the evening as users coined multiple hashtags like #ARRahman, #ARR and #MTV to tweet about the show.

During the VMAI (Video and Music Awards India), MTV opened voting via Twitter. It resulted in over 17,200 tweets with the hashtag #VMAI. The 60 nominees in various award categories were assigned a hashtag each to enable the public to vote for them over a period of three weeks. Data provided by the channel reveal that these hashtags cumulatively reached more than a million people and generated over 1 lakh votes, thus making tweets as influential as SMS votes.

Ekalavya Bhattacharya, head – digital, MTV India, says, “Our intention of being on Twitter is not to tell you that a show is on, but to engage you in a conversation around that and make you a part of the multi-screen experience.”

But who’s listening to all this Twitter chatter? And who can it benefit? The short answer to that is: Everybody.

BENEFITS OF THE BUZZ

Every stakeholder in the media and entertainment universe stands to gain from this convergence of mediums and the spike in interactive traffic.

Consider the potential: Broadcasters get real-time feedback on their programming which enables them to push popular content; advertisers gauge audience tastes better which allows them to position ads more effectively; Twitter gets more engagement, more promoted tweets, more hashtags and more paid-for trends; users get heard, their opinions valued. It can be a win-win proposition.

Twitter is a great tool to measure a programme’s impact. “Even if 5 percent of India’s 20 million Twitter users are talking about a TV show, that is 12-15 times more than what TAM measures with its 8,000 meters,” says Mahesh Murthy, venture capitalist and the founder of Pinstorm, a digital marketing and analytics firm. “Twitter data can really change the media and advertising ecosystem,” he says.

It can also alter the way people engage with TV shows and channels reach their audience. “I see this Twitter-TV relation as a modern day repeat of what happened in the 1950s when television channels in the West used print to carry weekly and monthly television guides where they informed people of the programmes that would run. Now, Twitter has become a way to discover TV programmes,” says Karthik Srinivasan, national lead, Social@Ogilvy at Ogilvy & Mather. “And this will allow media platforms to feed off each other.”

But are all stakeholders tuning into the Twitter buzz?

THE CHALLENGES

The current dearth of data on Twitter engagement has limited its value for the advertiser. There are no metrics for Twitter sentiments in India. There is no TAM equivalent in the social media space and the buzz cannot be benchmarked. This is a crippling factor for the Rs 42,000-crore Indian TV industry.

“It has been proven that Twitter buzz works very well for non-fiction shows. Advertisers are keenly aware of what is happening but they aren’t yet jumping onto the Twitter-TV bandwagon because the measurement is limited,” says Thakkar of KPMG India.

It is not surprising, then, that Anunay Gupta, co-founder & head of analytics, Marketelligent (a data analytics-based consulting firm), says, “There has been little or no instance where advertisers use social media buzz to find the target audience, or run ads in Twitter.”

In the West, Twitter has tie-ups with Nielsen (that announced the inaugural Nielsen Twitter TV Ratings in August), BluefinLabs (a social media-tracking firm Twitter acquired last year), eMarketer and a host of other digital analytics firms.

Sadly, India is not a “high-growth market” for them. In their 140-page IPO filing, India was mentioned only thrice and that too negatively when they spoke about governmental risks involved in doing business in the country.

Also, Twitter is haunted by how it is perceived in India: An elite medium for the affluent, English-speaking, SEC-A audience. Pinstorm’s Murthy says, “Twitter has a youth and English bias. That might put media buyers and advertisers off who will say that most of India’s TV-viewing audience that watches prime-time soap operas is not on Twitter.”

But Raj Nayak, CEO of Colors, a leading general entertainment channel, begs to differ. “Twitter is gradually increasing its consumption and adding audiences from tier II and III towns. We get a lot of traction from these regions,” he says.

And where the audience goes, the advertiser follows. Nayak is optimistic as he points out, “Advertisers are taking note [of this] especially for non-fiction properties. They pay a premium for big-ticket shows for the buzz they generate. And Twitter is a great engagement-driver.”

Colors’s Bigg Boss, one of the top-rated shows on TV, is also one of the leading shows on social, with extensive conversations happening every night around participants, controversies, entries, exits and show host Salman Khan, of course. An executive at a music channel says, “The Twitter-TV relation is overrated for any show that is not Bigg Boss or IPL. The volume of tweets generated during these two events is massive and doesn’t compare with the rest of the television universe.”

But is the alliance between Twitter and TV overrated? Or is it, more likely, a trend that is yet to peak in India?

THE INDIA STRATEGY

Though Twitter India head Rishi Jaitly declined to participate in the story, a communication from the global office said that the company’s India “strategy around Twitter and TV is the same as it is globally—help broadcasters connect to their viewers who are watching TV programmes and using Twitter to share that experience, publicly and in real time”.

Given the herd mentality of Indians, if one viewer shares his experience, another will and many more will follow. Ogilvy’s Srinivasan concurs, “If I log in and find people talking about a show, I would perhaps go and watch it for 10 minutes just to know what it is all about.”

He cites the example of a movie. When Singham premiered on Star Gold last year, Indian audiences were tickled by its dialogues. They took to Twitter to make witty comments about the film, and kept pulling in viewers to the channel. (Star Gold garnered a rating of 8.7 which is huge for any movie.) Most people started watching the film “only to be able to have a laugh” with the rest of their timeline.

That is Twitter’s ripple effect that turns a solitary act of TV-viewing into a large, live-event experience for the audience; it lures the user to sample on-air what everyone else is chirping about at that time. It is this ability to drive participation that is the company’s calling card.

Twitter has recently announced a partnership with Airtel Digital TV, the DTH arm of Bharti Airtel, to integrate tweets on digital TV for the first time. With the press of a button on their Airtel remotes, subscribers can view all the tweets about a particular show in real-time on their TV screens. If they keep tweeting about the show with the official hashtag, their own tweets will flash on the screen too. According to top social media tracker Mashable, “…the telco will stream targeted Twitter ads and marketing promotions to its TV subscribers.”

Industry sources suggest that Twitter is in talks with various TV channels, service providers, digital marketers and analytics firms to ink more such deals; this will improve its reach and help it narrow the gap with its rival Facebook that has already become a mass platform in India with huge ad spends being directed towards the site.

But selling on digital is still based on eyeballs and not engagement. “For a brand, engagement is most important. But media buyers always look at CPM [Cost Per Mille] and not CPE [Cost Per Engagement],” says Bhagia. “The metric that indicates impact needs to change. The entire selling approach has to change, both at the advertiser side and the channel side. The concept of transmedia content should come into existence.”

Disclaimer: Colors and MTV India are owned by Viacom18, a division of Network 18 – the publisher of Forbes India.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)