How Parag Milk Foods Got it Right with Cheese

Devendra Shah turned Parag Milk Foods into one of the most profitable dairy businesses. His secret: High-value milk products, especially cheese

In early 2008, a few months before the global economy went into a tailspin, Devendra Shah, the pudgy boss of Parag Milk Foods, took his boldest bet ever. In those days, India, which produces 127 million litres of milk a day, converted just 40 tonnes of that yearly flood into cheese, according to industry estimates. Most of this was made by Amul and sold to retail consumers.

Shah, who had set up his dairy 16 years ago in 1992 in Manchar, an hour’s drive from Pune, believed that India was on the cusp of a huge jump in cheese consumption. Now, this was before Indians had begun devouring pizzas faster than companies could serve them. Dominos had only 62 stores across India, a fraction of the 576 it has today. Other pizza chains, where they existed, were relatively smaller.

But Shah could not have known about the explosion ahead or the risks. If he had gone about analysing this opportunity in a conventional way—looking at the amount that would have to be invested, the return on that investment and so on—he would probably have decided it wasn’t worth the risk. But he did what a classic entrepreneur would—he deleted the Excel sheets and took a gut call. “I realised it was now or never,” he says. He decided that there was an untapped opportunity in processed cheese and that Parag Milk Foods would ride the coming wave. And Shah didn’t want to set up a small plant. He toured Europe for the best technology and by the end of the year he’d signed on for a 40-tonne cheese plant.

Overnight, Parag Milk Foods had doubled India’s cheese-making capacity.

It’s a decision that has paid off in spades. Cheese consumption has zoomed over the years and Parag has a lock on institutional clients such as Domino’s, Pizza Hut and Papa John’s. The company’s revenues have grown at a fast clip of between 20-30 percent in the last five years. It closed last fiscal with a top line of Rs 950 crore, most of it on the back of value-added products like cheese, ultra high temperature (UHT) milk and ghee.

Parag’s success has not gone unnoticed by private equity investors, hungry to be part of a growing, healthy, profitable business opportunity. Since 2008, the company has raised two rounds of capital from Motilal Oswal Private Equity and IDFC Alternatives. In September 2012, Motilal Oswal, which put in Rs 60 crore in 2008, diluted half of its 20 percent stake in favour of IDFC. (IDFC put in Rs 155 crore for a 22 percent stake.) Motilal made a 3x return.

The big question: What is Parag doing right that few other dairy entrepreneurs have managed to? Most of the players in the dairy business have remained regional players or have portfolios limited to commodity products like milk and curd. And, more importantly, in India’s Rs 33,200 crore dairy business (as estimated by KPMG), is this dream run sustainable?

Flashback

A generation ago, Shah’s family moved to Manchar, a small town 50 km north of Pune. They came from Gujarat as cloth traders and, for two decades, continued with this traditional business. In the 1960s, Shah’s father realised that farmers in the area had very poor yields from potato, their main crop. He began trading in seeds from Shimla, which produced potatoes with less moisture content. Yields went up and Shah’s family was now looked at with respect within the community.

By the late 1980s, the family had ventured into cold storages to enable local farmers to get better and steadier prices for their produce. While the Shahs were now established and well known, they spotted another opportunity—in the dairy business. This was a time when milk production in the country had zoomed and the farmers of Manchar had few takers for their milk, with supply in the region outstripping demand.

The contrarian Shah decided to set up a small 20,000-litre dairy—but not in the crowded, commodity end of the market.

Parag Milk Foods chose the small, but profitable, niche of skimmed milk powder. By 2004, the company, which also supplied milk to Mumbai and Pune, was the largest exporter of milk powder from the country. Shah’s studied gamble seemed to have paid off.

But danger lurked. Overnight, the government banned export of milk powder, citing a shortage of milk in the country and Parag’s main revenue stream dried up.

That was when Parag decided to invest heavily in building its brand—Gowardhan.

The Secret Sauce

Fast forward to February 2012. Girish Nadkarni of IDFC Alternatives was late in hearing about the business Parag had built. No matter, he still scheduled a meeting with the company and was pleasantly surprised with what he saw—a well-run company that was scaling up rapidly. He was hooked, but realised he had competition.

Edelweiss was already shopping around for good investments, and had signed seven term-sheets with Parag. According to Vikas Khemani, president at Edelweiss Securities, the term-sheets didn’t work out, as potential investors, including some large global names, wanted exclusivity.

Meanwhile, Nadkarni continued his research and got another crack at doing a deal in September. First off, Nadkarni realised that one of the reasons why foreign investors had been wary of investing was the company’s inability to monitor and track milk. But Nadkarni knew that was impossible in India. He visited the company’s milk collection centres and saw first-hand how unlikely it was for an Indian farmer to supply bad milk. “You supply it once and you will be ostracised within the community,” he says. He also got to experience the brand equity the company had built. People would walk 10 km to come to the nearest Parag milk collection centre.

But what of the company’s future prospects? India has seen several dairy companies languish in the Rs 500-600 crore range after showing initial promise. Even those which had broken the scale barrier, like Heritage (turnover of around Rs 1,609 crore) and Hatsun (Rs 2,165 crore), have remained regional players who have not grown outside southern India.

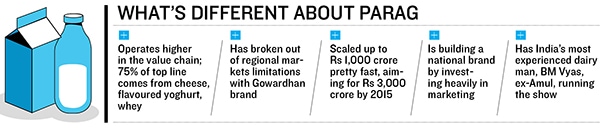

What makes Parag different is, simply, this. Unlike other dairy companies, which see 25-30 percent of their top line coming from value-added products, Parag generates 75 percent of revenues from cheese, flavoured yoghurt and ghee, all of which are value-added products.

What difference does the value-addition make to the margins? Let’s take cheese as an illustration. Producing a litre of cheese requires 12 litres of milk. This is milk that has high fat and SNF (solid non-fat) content.

After removing the fat and SNF, it costs the company Rs 190 for 12 litres. Cheese is sold at Rs 230 a litre, ex-factory, which results in a 14 percent margin. The fat and SNF content can be used to make whey proteins, another revenue stream. In contrast, a litre of milk has a margin of 10 percent, according to Nadkarni of IDFC Alternatives.

Parag enjoys better margins than companies like Britannia and Danone as, unlike them, it did not outsource any part of its supply chain. Let’s take a look at the comparative profitability. Parag made Rs 100 crore on a top line of Rs 950 crore, while Hatsun made Rs 44 crore on a top line of Rs 2,165 crore. “All its products are UHT-compliant,” according to Rakesh Sony of Motilal Oswal Private Equity. UHT-compliant means that even cheese doesn’t need a cold chain to be transported, saving the company money.

In addition to focusing on value-added products, Parag had worked hard at building a brand, Gowardhan. Parag hired Mahesh Israni as chief marketing officer from Hindustan Unilever and his efforts are showing. Since Israni’s arrival, packaging of Gowardhan products changed from the erstwhile staid and boring to stand-out and eye-ball catching. The Unilever DNA in Israni gave him the confidence to invest Rs 30 crore on advertising last year. A projected doubling of the media budget this year should help get better rates on television and print.

While Israni makes the product look slick and shiny, it is another key hire, BM Vyas, who is responsible for the reliability of the product. The story of how Shah brought him to the company is instructive. Soon after Vyas left Amul after a four-decade stint there, Shah drove to Anand in Gujarat and urged him to join the company. Vyas was hesitant, and it took a month of persuasion—and guarantees of a free hand in building the company and professionalising it—to get him on board. “I had seen how they operated at Amul. He had a strong will and got the job done,” says Shah.

Vyas sees Parag becoming an FMCG player from being a commodity company, something that would increase size and profitability immensely. “Parag will have Rs 3,000 crore in sales by 2015,” he says. For now, Vyas is working on increasing distribution and has managed to take Parag’s direct reach to 125,000 outlets across the country. To meet the growing demand, Parag has already added a second dairy at Palamaner in Andhra Pradesh. It is exploring the possibility of setting up one in the east of the country.

Cow’s Milk

Back in Manchar, on a rocky hillock, Parag has set up one of the most advanced dairies in the country. Shah, who was concerned about the bad image of Indian cows, has bred 3,200 Holstein Friesians. In cowsheds spread over 15 acres, the cows listen to soothing music, lie on soft mattresses, are kept cool with water sprays and have scrubbers to clean themselves. At a rotating platform, cows are trained to enter an electronic and automated milking station. All it takes is six workers to complete the milking process. These cows, on an average, yield 14 litres of milk a day compared to 7 litres for the average Indian cow.

Parag has also used the cows as a good marketing opportunity. Under the Pride of Cow brand name, the company supplies fresh milk to households in Mumbai at a cost of Rs 75 a litre. It has managed to get 1,000 customers, including the likes of Mukesh Ambani, for this by-invitation-only product.

For now, Parag plans to take the business to regions where the company doesn’t have a strong presence or where there is an apparent demand-supply mismatch. Take Kashmir, which doesn’t have much milk production, forcing people to rely on milk powder. Parag’s launch of UHT milk in Kashmir has been well received.

And finally, we see Parag raising Rs 80 crore from the International Finance Corporation to set up a whey plant. Whey proteins are highly profitable by-products in the manufacture of yoghurt and are sold as protein supplements—and Parag is now only the second in the country after Amul to enter this lucrative market.

If Amul has become The Taste of India, Parag is well-positioned to take a bit of that taste. If you are not No 1, you try harder. That’s what has got Parag thus far. It has always tried harder, thought different and believed in itself.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)