India needs energy-efficient buildings, today

If India wants to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2070, energy-efficient buildings are an important piece of the puzzle. But there has been little progress in that direction

Green walls or vertical gardens can increase energy efficiency, reduce indoor and outdoor temperatures, and improve air quality

Image: Shutterstock

Green walls or vertical gardens can increase energy efficiency, reduce indoor and outdoor temperatures, and improve air quality

Image: Shutterstock

The market size of the real estate sector in India is estimated at $477 billion, contributing to 7.3 percent of the total economic output, according to a 2023 Naredco-Knight Frank report. This is expected to expand to $5.8 trillion, or 15.5 percent of the total economic output of the country, by 2047.

The demand for buildings and rate of construction activity are going to increase due to factors like rapid urbanisation and growing disposable income of people. Real estate is also a job-creator, accounting for 18 percent of the total employment in the country, as per the report.

The potential of the real estate sector is representative of the economic growth path on which India finds itself today. The Union Finance Ministry, in a report released in January, said India can aspire to become a $7 trillion economy by 2030. Right now, this growth is powered by a dependence on thermal power like coal, gas and diesel, which is environmentally unfriendly.

So, over the next six years, India wants at least 50 percent of its energy requirements to be met by renewables, and bolster its non-fossil fuel capacity to 500 GW from around 200 GW currently. The country’s ultimate goal is to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2070.

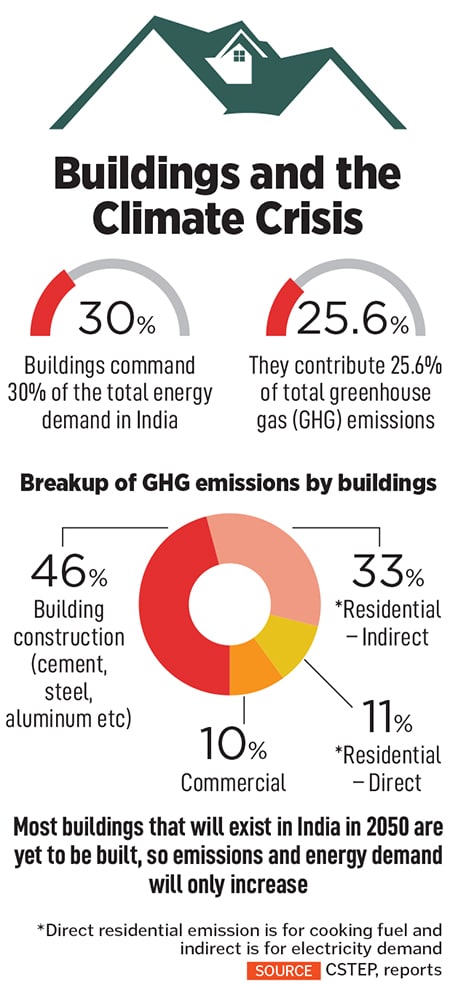

Buildings are among the leading demand drivers for energy in India, and hence decarbonisation in the sector assumes importance. They currently command 30 percent of the total energy demand in India, which translates to 25.6 percent of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, according to a March report by The Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP), a think-tank.

(This story appears in the 26 July, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

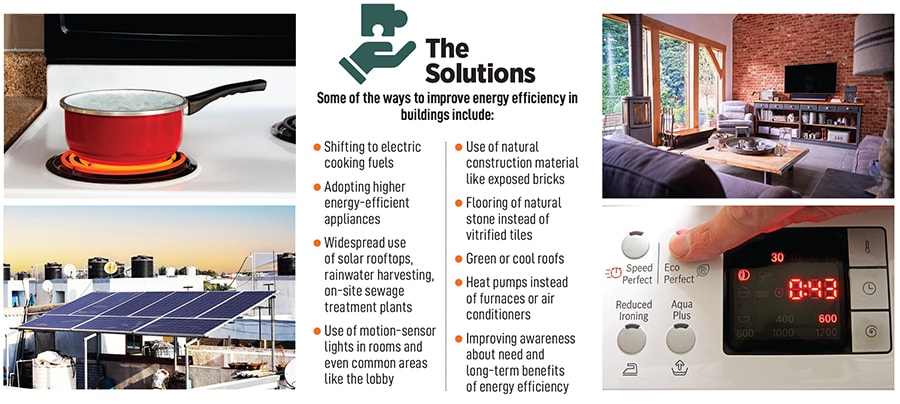

If India follows a buildings-led intervention trajectory for decarbonisation, says the CSTEP report, we could achieve a 43 percent emission reduction from buildings. Some of the solutions here would be shifting to electric cooking fuels, adopting higher energy-efficient appliances and widespread solar roof`tops.

If India follows a buildings-led intervention trajectory for decarbonisation, says the CSTEP report, we could achieve a 43 percent emission reduction from buildings. Some of the solutions here would be shifting to electric cooking fuels, adopting higher energy-efficient appliances and widespread solar roof`tops. Giving people reasons they can personally relate to or care about is necessary, says Khan of CSTEP, because right now, they do not see any immediate tangible benefit of investing in a sustainable or energy-efficient property. She also believes that if developers can go back to certain traditional practices, that can bring the housing cost down, make it sustainable and thermally comfortable.

Giving people reasons they can personally relate to or care about is necessary, says Khan of CSTEP, because right now, they do not see any immediate tangible benefit of investing in a sustainable or energy-efficient property. She also believes that if developers can go back to certain traditional practices, that can bring the housing cost down, make it sustainable and thermally comfortable.