Two sides of the Infosys coin

Incipient though it is, Vishal Sikka succeeded in getting 200,000 Infoscions on a journey of transformation and, equally important, of seeing themselves as real innovators and not just as warm bodies. But his resignation over persistent 'attacks' from founder NR Narayana Murthy has served to bring into sharp focus issues of corporate governance and cultural discord at Infosys with no real solutions in sight

Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy’s (left) continuous assault resulted in Vishal Sikka’s resignation, the IT major said in a statement

Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy’s (left) continuous assault resulted in Vishal Sikka’s resignation, the IT major said in a statement

Image: STR/AFP/Getty Images

The painful irony cannot be lost on anyone, least of all NR Narayana Murthy.

Infosys has long been considered the final word in corporate governance. The founder, who turned 71 on August 20, has taken immense pride in the IT major’s credibility in the country and abroad. As Harsh Goenka, chairman of RPG Enterprises, puts it: “Infosys as a company has always been looked at as the gold standard due to an egalitarian culture and focus on high corporate governance.”

Which is why, the last year should be particularly troubling, both for its founders and the current management. The company has been under the scanner for both corporate governance and, worse, management-founder conflict, the latter leading to the events of August 18—the resignation of Vishal Sikka, its CEO and managing director (MD), under undoubtedly bitter circumstances.

“Over the last few days, I’ve been thinking this through with the board to see what could be done here, and finally, earlier today, we came to the conclusion that I just can’t do this anymore and I want to leave,” Sikka, 50, told investors, and later, reporters, in a press conference from Palo Alto, US, a few hours after the announcement of his resignation. The markets—and Infosys shareholders—reflected the hurt. The Infosys stock was down 9.6 percent by end of day on August 18, and was more than 14 percent down at the close of trading on August 22.

Sikka was, of course, referring to the year-long battle between Murthy, now a minority shareholder, and the company’s board which had turned increasingly vicious and personal, according to Sikka and the board.

In fact, that very morning, financial daily Mint reported an email from Murthy to “advisors” in which he said he was told by three independent directors on the company’s current board that Sikka was more chief technology officer (CTO) material. Murthy even named Ravi Venkatesan, co-chairman of the board, as one of those three directors. He also made public two letters, along similar lines, that he had written to the unnamed advisors and the company’s board.

Infosys released a strong statement in response: “Murthy’s continuous assault, including this latest letter, is the primary reason that CEO Vishal Sikka resigned despite strong board support.”

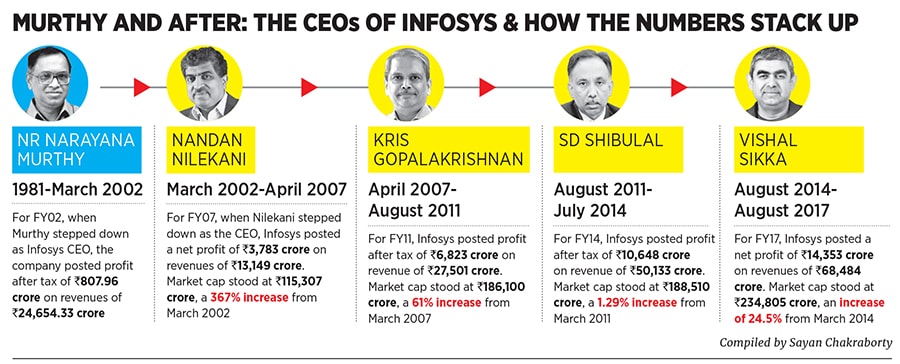

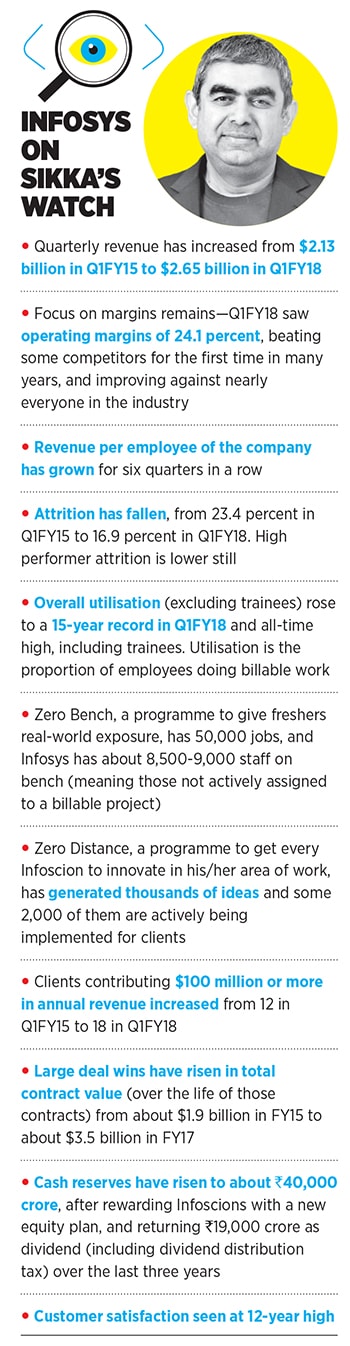

The support from the board was based primarily on the turnaround Sikka had effected at the Bengaluru-headquartered IT behemoth: During Sikka’s three-year-long watch, Infosys had added over $2 billion in new incremental revenue, half of which had come from new software and services that didn’t exist earlier. Infosys, now a $10-billion company by revenue, had also won back industry leading growth at 8.3 percent constant-currency increase in revenue for FY17; margins were stable due to strong execution for multiple quarters and the company’s cash reserves were over $6 billion, from about $4.9 billion three years ago.

The board has now named Sikka executive vice chairman, and current COO UB Pravin Rao as the new CEO and MD, reporting to Sikka, with immediate effect. The company will look for a permanent chief executive to be in place no later than March 31, 2018. And whoever that is will have some big shoes to fill and serious value to rebuild.

But as recent events have shown, for that person to be effective, the board will have to ensure that the real concerns around corporate governance and cultural mismatch are addressed.

A Matter of Governance

Over the last year, Murthy has kept up pressure on the board (led by Chairman R Seshasayee) and on Sikka on what he termed “governance issues”, through newspaper and television interviews. He had asked for the findings of independent investigations into the $200-million acquisition of an Israeli automation specialist, Panaya Inc, and into payouts made to a former CFO and a former general counsel to be made public.

Murthy had alleged that the payout to former CFO Rajiv Bansal, who left the company in December 2015, was “hush money” to cover up an overvaluation of Panaya. The investigations were set in motion after allegations by an anonymous whistleblower in early 2017. The probe found no wrongdoing by Sikka, Infosys said in a statement in June this year.

“There was a demand that the report of the investigation into the Panaya transaction be made public. We support this demand since a company should be transparent if it is to be considered the gold standard of corporate governance. But the way in which other issues have been raised by the founders, led by NR Narayana Murthy, outside the board is not something that can be supported,” says JN Gupta, MD, Stakeholders Empowerment Services, and former executive director at the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi).

At the time of writing this story, Murthy and his co-founder promoters own a tad shy of 13 percent of the company. And the widely held view among heavyweights in India’s capital markets, other institutional investors and business leaders is that “the entire saga has led Infosys’s investors to suffer value erosion”, in the words of Gupta. He adds: “Murthy and the other founders collectively own only 13 percent in the company. But it is the weight of their reputation with which they are bulldozing their way through at the expense of others. If an overwhelming majority of the company’s shareholders don’t have a problem with the current management or board, then they can’t be held to ransom for what a minor section of shareholders feels.”

But Murthy’s questions remain, and Infosys may need to disclose more than it has thus far.

“If you are a promoter [which is how Murthy and his co-founders are classified on the exchanges], you are responsible for corporate governance. The promoters will get a notice from Sebi if anything happens and they [the promoters] have to defend it,” points out former Infosys CFO Mohandas Pai. “So Murthy has every legitimate right to demand answers pertaining to corporate governance from the board. Murthy has not commented about the CEO or on strategy or the management of the company.”

Shriram Subramanian, managing director of Bengaluru-based independent corporate governance research and advisory firm InGovern, also points out that “Murthy is well within his rights to ask questions”. “The problem is with the manner in which he’s been asking and the number of questions that he’s been asking repeatedly,” says Subramanian, who is also the former head of wealth and asset management at Infosys Consulting, a division of Infosys.

To combat this, the need is for better transparency going forward, indicates Indian School of Business Professor Kavil Ramachandran. “The board should develop a succession management process, which means that it should have a review of the performance, whether decisions were taken properly or not. Even in the quarterly meetings, it should devote some time for this, and there should also be offline communications with the CEO,” he says.

A Cultural Mismatch

Infosys’s next CEO will have to deal with complexities at multiple levels. But everything that has happened has certainly made it difficult to attract someone of high calibre.

A popular view is that an insider might fare better. (At the time of writing this, there was speculation that co-founder and former CEO Nandan Nilekani* may come back in some capacity.)

Goenka draws parallels with how long-time Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) veteran N Chandrasekaran, now heading the Tata group, is smoothening the ruffles after the conglomerate’s tussle with Cyrus Mistry. “Someone who understands the Infosys founders’ mentality, as well as the present imperatives before the company, is needed,” he says. “What has happened over the last 2-3 years is unfortunate. They brought in a new CEO with impressive credentials who was trying to make fundamental changes to the company and was making some right moves in terms of shifting focus to digital technologies,” adds Goenka. He believes “the current tussle at Infosys is the result of a clash between the founders’ mentality and the approach of the current management”.

But at the same time, Venkatesan, on August 18, made it clear that there will be no divergence from the direction the company is already on. “We need someone who is transformational. That is something that has become clearer and clearer to us in these last three years,” he said. The industry is changing at an accelerating rate and the new leader has to be someone who can build on what Sikka had helped Infosys achieve, he added. “This is no longer just Vishal’s vision. It started out that way, but over the last three years, many of us engaged and partnered, it is now very much institutionalised and it is now very much Infosys’s vision.”

A few months ago, the board constituted a committee of directors, which includes Seshasayee, another independent director DN Prahlad and Venkatesan. The committee has worked hard to help accelerate the execution of this vision of an Infosys that delivers Artificial Intelligence-led solutions, he said. “All of us have to move faster, and we need a person with a transformational mindset who shares this vision. We can’t afford to do a reset on the strategy or go back on it.”

ALSO READ:

It's critical for Infosys to be a company of innovators: Vishal Sikka

Murthy is a hero. Yet, he faltered

For instance, Infosys currently has 9,500 ongoing projects. The greater proportion of them still comprise providing more conventional time- and material-based application development and maintenance services. But an increasing share falls into the category of the new, exciting find-the-right-problem type of services that Sikka had begun to get the company to offer clients. “We have been working to create a culture where [the people who lead] these 9,500 projects think of themselves as 9,500 entrepreneurs,” Sikka told investors and analysts during the conference on August 18.

However, while the board insists that Sikka’s strategy is the right course, “it will be very difficult for them to bring in an external person at this stage”, says Ramachandran. “Given Sikka’s experience and given that the board structure is like this, I don’t think anyone who is senior enough will jump in for this kind of a job.” Comparisons with the Ratan Tata-Mistry conflict are inevitable. However, adds Ramachandran, the difference is that “unlike the Tata group, this is a single company”. The need, he points out, is of an objective introspection by the board; and two, of a strong chairman who is a visionary institution builder, who will groom the CEO.

Ravi Venkatesan has denied being in the running for CEO

Ravi Venkatesan has denied being in the running for CEOImage: Joshua Navalkar

Resolving Founder Conflict

The appointment of Prahlad, a software entrepreneur, who is related to Murthy, to the board and even the elevation of Venkatesan as co-chair were seen as steps taken to appease Murthy’s concerns. The board in its statement also said that, over the last year, it has engaged in dialogue with the founders to understand the real concerns and address them, find solutions within the boundaries of the law, without compromising the board’s independence. “We think we’ve done everything that’s reasonable, but at some point, being an independent board, we make our own decisions and that has not gone down particularly well [with Murthy],” said Venkatesan, who is a former chairman of Microsoft India, and the current chairman of Bank of Baroda, one of India’s largest state-owned banks.

Ramachandran, however, thinks that “vehemently supporting Sikka and blaming Narayana Murthy for everything” at this stage is irrelevant: “Where was this board when Sikka was attacked by Narayana Murthy? Except for denying some of those things, did it counter Murthy through a public campaign? Or restore the confidence of the team?” he asks.

In any case, matters shouldn’t have been allowed to reach this impasse, says Subramanian. “I don’t want to paint anybody as a villain. It takes two hands to clap and both sides are at fault. Nandan Nilekani, too, could have intervened in the past and acted as a go-between, between Mr Murthy and the board,” he says.

What is clear is that before any potential candidate agrees to fill Sikka’s shoes, a way must be found to resolve these “founder issues”, said Venkatesan. That process, however, will not involve inviting Murthy back, he asserted. Venkatesan also firmly rejected speculation that he might himself be in the running for the CEO’s post.

Most indications are that change is here to stay at Infosys. “The founders may have had a certain way of functioning and their own thoughts on how Infosys should be managed. But now that they aren’t a part of management anymore, everyone else can’t be expected to follow the same style,” Gupta says.

Pai thinks that institutional investors should talk to Murthy to understand his perspective. “And they should all come together and decide for themselves what they have to do. The right thing to do is to get two directors from the founders’ side on the board,” he says.

Like the man (temporarily) in charge, Pravin Rao, said, there is “no easy solution, no short cut”. “We have to focus even more on communication, and performance will help, from quarter to quarter,” he said. And that starts immediately from the current quarter itself. “The balance sheet was never stronger than it is today, from whichever angle you look at it,” Mavinakere D Ranganath, the company’s CFO, said. “So we continue to focus on execution.” Indeed, Infosys has decided to go ahead with a proposed share buyback—a first in the company’s 36-year history—to return more than $2 billion (`13,000 crore) to shareholders.

Ranga, as the CFO is known within Infosys, “has worked incredibly hard” in the days and months leading up to the board’s approval of the buyback on August 19, to secure approvals across multiple regulatory regimes, Sikka said. About 17 percent of Infosys’s public shareholding is in the form of American depositary shares, which entailed approvals from US Securities Exchange Commission as well.

The focus, though, has not been as much on the company and its future as it has on who is to blame for this turmoil. And several fingers are being pointed at Murthy. A common refrain: He should have handled it better.

“If he is a patriarch-like person, he could have called all of them together and said, ‘Look, I think there is a drift happening, or we are not on the same page. I’m not the formal chairman, or formal controller of the business, but I’m interested and let’s sit down, look at this objectively if we’re going in the right direction or not’,” suggests Ramachandran. Instead, he took the battle public through the media.

“In his latest letter [written to the Infosys board on July 8, 2017], he has largely talked about governance. But this letter is not the genesis of the problem,” says Subramanian, adding, “Will bringing an internal CEO solve the problem and keep Mr Murthy quiet? No! Neither has Mr Murthy asked for it nor did he ask for Sikka to go.” As someone who had worked at Infosys when Murthy was the chairman, he points to Murthy’s tendency to be “a micromanager”. “He’s passionate about it [Infosys] and he’s not letting go. And this is the fundamental problem.”

But that doesn’t justify the board’s actions, says Pai.

“The letter by the board [which targeted Murthy] was in very bad taste. They made charges without evidence and data. Never in the history of any company has the board made any charges against the promoters in a letter to the stock exchanges. They did it only to switch the blame for their misgovernance and shifted the blame to Murthy.”

Pai highlights another trigger for Sikka’s exit: “He [Sikka] also gave a very tall target of achieving $20 billion [in revenue by 2020]. I don’t think the board had approved the target and there was no plan behind that target. How can the CEO give such a tall target without taking the board into consideration?”

Manish Sabharwal, co-founder and chairman of TeamLease Services, agrees: “CEOs must realise they will be judged by their promises: None of this drama would have happened if the company was on track for the CEO’s self-declared $20-billion target.”

What could have also helped is a better-planned transition for Murthy. “Founders must transition from CEOs to board members to shareholders: In this case, jumping from CEO to shareholder was too big a leap,” adds Sabharwal.

And founder-shareholder Murthy is not giving up the fight just yet. He has said he will reserve his next salvo for a time of his convenience in a forum of his choice. Clearly this saga is far from over for the Infosys world and also its observers.

It is, though, endgame for Sikka, who was visibly tired during the videoconference on August 18. It would have been 1.30 am in California when he started the press confrence. He was wearing his trademark round-neck black T-shirt, and the dark colour seemed appropriate for the circumstances. A grim-faced Seshasayee sat next to him. And a few thousand employees, tens of thousands of investors and the IT world watched as another giant grappled with reality.

* On 24 August 2017, Infosys brought co-founder Nandan Nilekani back as non-executive chairman with immediate effect.

This story will appear in the 15 September, 2017 issue of Forbes India.

ALSO READ: