Unilever's Bargain Offer: Should You Hold On or Tender Your Shares?

The consumer packaged goods giant has launched an open offer to buy back shares of HUL. Should investors rejoice?

On April 30, Ramesh Damani was in for a pleasant surprise. The value of a substantial holding in his portfolio, Hindustan Unilever (HUL), had overnight zoomed 20 percent on the back of the news that Unilever was launching an open offer to buy back HUL shares. “I was jubilant,” says Damani, a successful stock market investor. “There’s no way I’ll be surrendering my shares at these prices,” he says.

Damani had every reason to be happy. He’d long argued that the world over, consumer businesses were among the best to own as investors looked for stable growth, good cash flows and, in time, a high price to earnings multiple (PE). Now, he’d received an endorsement from the strongest possible source: Paul Polman, the global boss of the €50 billion consumer packaged goods giant Unilever, the world’s second biggest consumer packaged goods firm.

While both Damani and Polman may have different reasons for their bullishness, the net result is the same—consumer businesses in India are extremely valuable. In the last five years, the BSE FMCG index has returned 242 percent, the highest among any index.

Polman, who sees emerging markets (they bring in 55 percent of revenue) as the next big lever of Unilever’s growth story, is investing big in the India growth story. After HUL hit its stride in the last four years, its parent company believes that this is an opportune time to invest in the next phase of growth in India.

At $5.4 billion (Rs 29,220 crore), this ranks as the largest open offer for an Indian company by its global parent. Simply put, HUL will pay shareholders Rs 600 a share for every share tendered—a 20.3 percent premium. In November, GSK Consumer had spent Rs 5,221 crore to buy back shares in its Indian subsidiary. With strong growth in the Indian consumer market, analysts at IDFC expect subsidiaries of Nestle, P&G Hygiene and Colgate Palmolive to follow suit.

That’s why Polman’s open offer holds an interesting mirror to the Indian growth story. On the one hand, the fact that global firms like Unilever see higher potential for growth and earnings in markets like India, compared to their home markets in Europe and US, is beyond doubt. This current surge in confidence comes at a time when simmering doubts about the inherent strengths of developing and emerging markets, particularly in the last two years, have cast a pall of gloom over the broader investment climate.

Yet, whether this decisive shift in the balance of power towards emerging markets translates into rich pickings for Indian investors is far from clear. For instance, would Damani be better off staying invested in Hindustan Unilever? Or should he tender in his shares and seek to earn higher returns from a clutch of other consumer stocks that may not quite have the sheen or pedigree of a HUL stock but have generated consistently higher returns?

We’ll get to that in a bit. But first, what made Polman craft his open offer in the first place?

The India Logic

It’s not hard to see why he took this bold call. When he took over at Unilever in 2009, Polman had laid out an ambitious goal—to double revenues. While he’s not set a timeframe, Polman has emphasised that it wasn’t the €80 billion number in itself that was important, but inculcating a mindset of growth that was crucial to the company.

In the last three years, Unilever has made rapid strides in getting there. Polman has managed to add €10 billion to take the topline to €50 billion in the last three years. And a bulk of that growth came from emerging markets. While mature markets like the US and Europe have slowed, Unilever’s subsidiaries in places like India, Indonesia and Nigeria have been firing on all cylinders. Profits growth at HUL, for instance, has increased to 11.4 percent a year in the last five years, versus 5.2 a year in the last decade.

But there’s one big hole in Unilever’s portfolio: China. Here, Unilever has some catching up to do. Analysts estimate that P&G is eight times larger than Unilever (both companies do not break out individual country sales). Polman realises that bridging the gap in China is not going to be easy. Instead, according to a chief investment officer at a leading local fund house who prefers to remain anonymous, the open offer may be a signal that Polman may have decided to instead hitch a ride with the Indian growth story.

“From Unilever’s perspective, given their low cost of capital and long time horizon, much longer than even for long-term investors, a 2.6 percent return on capital in euro terms that would grow further over the years would make sense,” says Bharat Shah, executive director at ASK Group.

More importantly, in buying into the Indian subsidiary, Polman is getting a higher return on capital than his cost of borrowing. With cash reserves of €3 billion, Unilever would have to borrow very little to pay for the additional stake in HUL. Analysts say its borrowing rate is likely to be 1 percent at most. HUL’s earnings per share for FY13 was Rs 17.6. At a purchase price of Rs 600 a share, Unilever stands to make 2.6 percent a year. And with profit likely to grow every year, the return is only likely to increase. “If one takes a long-term thirty-year view, then it is a good deployment of their cash,” says Rajeev Thakkar, chief executive at Parag Parikh Financial Advisory Services Ltd.

Not everyone is equally supportive of Polman’s decision. An analysis published by Reuters Breakingviews says Polman, who declined to speak to Forbes India, could have spent $4.7 billion to buy back 110 million of its own shares and boost its earnings more, at least in the short run, than the HUL buyback would.

But Polman is not one to take a short-term view. Soon after he took over in 2009, he refused to issue earnings guidance, saying the short-term thinking distracted the company from focusing on long-term profitable growth. He’s also focussed not only on topline and bottom line growth but also on volume growth, which he argues is a key metric of the health of a business. In contrast to buying Unilever stock, the HUL buyback is expected to add no more than a few percentage points to Unilever’s earnings.

For HUL, the global CEO’s confidence might be a shot in the arm after a period of painfully slow growth in the last decade, when both revenue growth and profit growth slowed between 2001 and 2007. Its stock price stagnated at the early Rs 200 levels. It’s only after April 2008, when Nitin Paranjpe took over as CEO, that the company has resumed its growth trajectory. So, long-term holders of the stock have seen their shares appreciate by 9.4 percent annually, while those who entered five years ago have seen them rise by 13.5 percent annually.

Over the course of the last decade, HUL has also become much more closely aligned with its global parent. Most important functions like research and development, human resources and so on are now shared. Company insiders say there is a far greater cross pollination of ideas between India and other subsidiaries. In January, HUL’s board voted to up royalty payments to Unilever from the present 1.4 percent to 3.15 percent by 2017, signalling another important intention to align more closely. And lastly, the company is working on an ambitious plan to treble its rural direct distribution reach. With this, HUL has taken an important step to position itself for faster revenue growth in the years to come, say analysts. With a strong long-term outlook, it’s no surprise that Polman has chosen to make this bet.

The Next Decade

While there’s a strong argument for Unilever to up its stake, fund managers argue that there is an equally strong logic for minority investors to surrender their stock. On the face of it, that might seem like a piquant situation. Surely what’s good for Unilever is good for the minority investor? Apparently not, say analysts.

For starters, HUL is likely to see a margin squeeze in the years to come. As organised retail ups its pie in India from 6 percent at present to 12-15 percent over the next decade, the ensuing battle for margins between retailers and consumer companies will only increase. Add to that competition from private labels and the picture only gets worse. In developed markets, both P&G and Unilever have had bruising battles with the likes of Walmart and Tesco. There’s little to suggest that this phenomenon will reduce the pricing power of consumer packaged goods firms.

Second, consumer goods companies in India will have to brace themselves for market share battles. In 2009, HUL and P&G sparred on detergents and Thakkar (of Parag Parikh Financial Advisory Services) says there is no reason why such skirmishes couldn’t happen again. Colgate Palmolive has shown itself to be a worthy competitor in the toothpaste space. Home-grown Indian conglomerates have also upped their game in the past few years and are now formidable competitors. “The barriers to entry in this space are very low,” says a prominent fund manager who requested anonymity.

Third, as the competitive intensity in the Indian market increases, companies are being made to work harder to make their products noticed by Indian consumers. Advertising and promotion expenses are rising, further crimping margins. Since 2007, advertising spends for HUL as a percentage of sales have gone up from 10.6 percent to 12.5 percent in 2012.

Fourth, there’s the spectre of high commodity prices. The last decade has seen a commodity super cycle with crude and palm oil staying at peaks for the last four years. High commodity prices drove down gross margins at HUL from 51 percent in 2010 to 47 percent in 2012, according to Morningstar. Palm oil prices have eased in the last six months, but it’s anybody’s guess which way they’ll go in the next decade.

While there is nothing to suggest that these same competitive pressures won’t apply to other consumer goods companies, HUL being the largest could suffer greater damage. At some point, its sheer size could start to weigh it down and make it harder for it to grow. Also, smaller competitors would begin to nibble away at the margins. Regional brands have in the past given the company a run for its money—Wheel two decades ago and more lately Ghadi and Cavinkare.

So what does the minority shareholder do?

The answer would depend on whether you believe the Indian market offers relatively better opportunities for wealth creation. According to Sanjoy Bhattacharyya, managing partner at Fortuna Capital and a Forbes India columnist, there are indeed other stocks that an investor can put money in to generate a higher return.

First, let’s see how much investors can make, if they stick with HUL for the next decade, a reasonable time horizon for a long-term investor. At present, HUL has earnings per share of Rs 17.5. Over the last five years, the company has grown profits by 11.4 percent. Now, let’s assume a best case scenario—the company grows faster, margins improve and more people up trade to its higher value products. With a profit growth of 18 percent and a price to earnings multiple of 30, the stock would trade at Rs 2,730 a decade from now, or an annual gain of 12 percent.

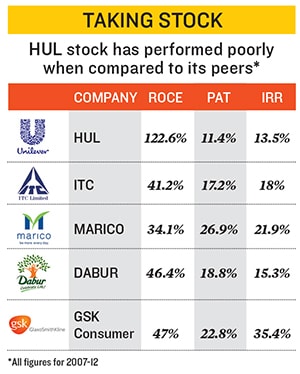

This, according to analysts, is not enough. As our table shows, HUL’s competitors—ITC, Nestle, Colgate Palmolive, Dabur and GSK Consumer—have all grown faster than HUL in the last five years. Also, one has to remember that the parent will take away royalty income, which made up 2 percent of profit last year.

Shah of ASK says the justification for a Rs 600 price per share would imply a compounded profit growth of 18 percent for the next decade fetching investors a 12 percent return. According to Shah, given HUL’s history and the size of the opportunity, that sounds like an ambitious target. He points to stocks like Asian Paints, Nestle, ITC, Marico, Page Industries, TTK Prestige that are likely to give a much better return. His view is consistent with the analysts Forbes India spoke to. If an investor’s time horizon is under five years, they’d advise their clients to sell. They declined to be named as they are not authorised to discuss specific stocks.

What if you hold out?

Still, there are some investors who plan to hold out. LIC, which has a 3.13 percent stake in HUL, does not plan to surrender its shares. According to an article in Business Standard, an LIC official said the company felt the HUL stock would rise from its current levels, and the premium offered by Unilever wasn’t attractive enough. Domestic institutions and mutual funds are expecting about Rs 1,000 a share. They say that as they are long-term investors, they would not disinvest their shares in the open offer.

However, even for the Glaxo open offer, financial institutions like LIC initially said they would not sell their shares, but later changed their mind. So whether such posturing gives way to pragmatism in this case remains to be seen.

It’s also unlikely that enough individual shareholders will surrender their stock for the company to get to the 75 percent mark. HUL has so far maintained that it does not plan to delist.

Some of this behaviour may be partly linked to emotion, rather than rational logic. After all, for many long-term investors, HUL was indeed the gold standard. The stock gave them consistent returns for decades. Despite the setbacks in the better part of the last decade, investors still attach a sense of security to the stock.

Meanwhile, Damani says he has no plans to surrender his shares. The Unilever offer is a vindication of the fact that HUL still has a lot of growth to come. According to him, the business is growing, has consistent cash flows and has a good return on capital.

“In a market where there are such few quality stocks, why surrender one of the few quality stocks you have?” he asks. He scoffs at the notion that consumer stocks are expensive. What’s to suggest the price earnings multiple won’t reach 50 tomorrow, he asks.

Damani may well be proven right. For the moment though, most experts aren’t ready to take a long-term call on the stock that was once the darling of the Indian markets.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)