India's New Warehouses

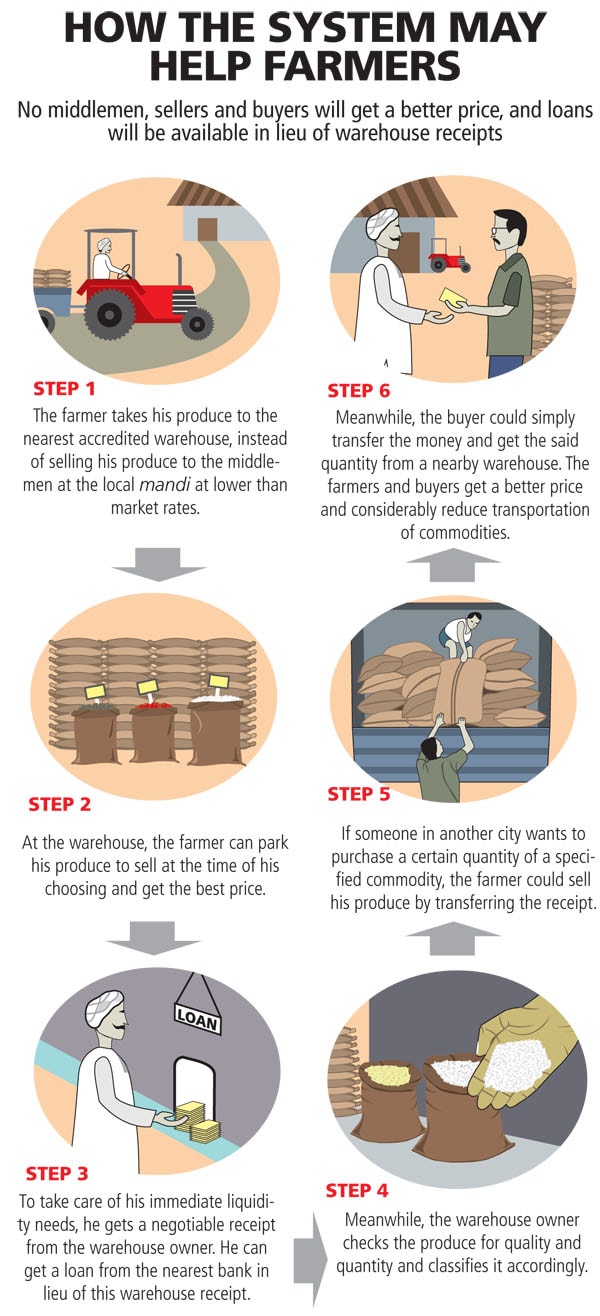

Through a new system, the government plans to improve storage and help farmers get a better deal

One issue, other than corruption, that has troubled the UPA government since its first term, is inflation, especially food price inflation.

But most analysts believe that though India needs to improve its productivity, there are enough food grains in the country to feed the teeming millions. The real worry is about the supply chain or the lack of it, to be precise.

Estimates suggest that India wastes almost 20 percent to 25 percent of its food grains due to improper or inadequate storage. That is roughly 60 million tonnes of food grains each year, almost as much as what India actually stores in its official godowns. The degree of wastage is nearly double in the case of easily perishable commodities like fruits and vegetables.

Infographic: Hemal Sheth

It was in this context that the government instituted the Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA) in October last year. The idea was to improve the storage capacity in the country and also help producers and consumers get a better deal by cutting out the intermediaries and wastages. The 2011-12 Budget also recognised cold chains and post-harvest storage as an infrastructure sub-sector eligible for income tax relief.

The initial focus for the WDRA has been the agricultural sector. Thus, starting April 2011, the central government announced the Rural Godown Scheme to promote the construction of warehouses in the rural areas.

The WDRA, on its part, has devised the system of Negotiable Warehouse Receipts, which will, in time, allow farmers to get the best price for their produce and help bring down prices of commodities by cutting out the arbitrage earned by middlemen (see graphic). At present, the scheme covers 40 agricultural commodities like cereals, pulses and spices.

“Earlier, farmers used to engage in panic sales since they were in dire need of money immediately after the harvest, primarily to pay off many of the loans they had taken for agriculture. They had little bargaining power against the local trader since farmers had no space to store the food grains safely,” explains Dinesh Rai, chairman, WDRA.

As of now, most warehouses in rural India are for captive use, with very few actually surviving as standalone businesses and typically there are four to five middlemen between the producer and buyer.

However, over the last few months, the WDRA has registered 50 warehouses across the country, which will now be able to issue such negotiable warehouse receipts. For getting such a registration, a warehouse has to be accredited by one of the eight accreditation agencies chosen by the WDRA. These agencies, four each in the public and private sector, ensure that the warehouse concerned has the wherewithal to not only safely store the commodities, but also have the ability to index them according to the quality and ‘best before’ dates. WDRA has tied up with the Indian Banks’ Association to ensure that banks also honour the receipts from registered warehouses.

Rai says that another 300 warehouses are in queue for accreditation. He expects this number to rise after three to four months, once the WDRA links the registered warehouses with spot exchanges through the introduction of electronic receipts, the DMAT account equivalent of warehouse receipts.

The actual storage in the warehouses is yet to start as the WDRA is running an awareness campaign across the country to familiarise farmers with the process. In time, Rai expects to focus on developing industrial warehousing as well as promoting the cold chain to ensure that fruits and vegetables are also brought under the warehousing provisions.

The Downside

While the WDRA’s move is likely to benefit all concerned, not everyone is convinced that the eventual roll-out will happen without any hiccups.

One issue is the extent to which small and marginal farmers would benefit, since they often have very small quantities to store, which may not always be attractive for warehouses.

Madan Sabnavis, chief economist of CARE Ratings, says this issue will only get resolved over time. Initially, a warehouse may focus on acquiring the bigger accounts, but as the store gets filled up, it will focus on the smaller players. Others suggest the formation of producer groups by farmers to

ensure viability.

In future, industry watchers also apprehend some turf war between the WDRA and state governments. This is because spot exchanges for agricultural commodities are governed by the state legislations and as such the WDRA may find itself incapable of resolving problems if there are trade irregularities in a spot exchange. But Anjani Sinha, CEO of National Spot Exchange, assures that exchanges are required to comply with the WDRA norms too.

Another apprehension of the industry is that the government will need to bring in a separate legislation to make the warehouse receipts truly negotiable instead of a mere document that establishes ownership. However, Rai says that a separate legislation is not required.

In fact, the WDRA is currently drafting electronic warehouse receipts’ regulations within the Warehousing (Development & Regulation) Act 2007. These regulations are expected to come into effect in the next two months. Notwithstanding these procedural issues, the logistics and warehousing industry have welcomed the creation of the WDRA as “one of the best developments” in this field.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)