Actavis and the art of billion-dollar drug dealing

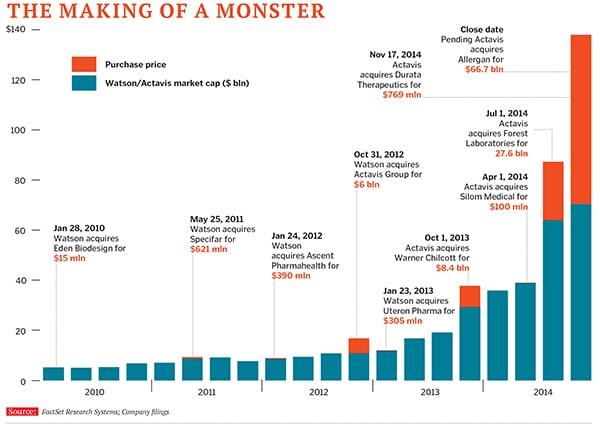

Brent Saunders generated $25 billion in value for investors by flipping drug companies rather than discovering new drugs. Is this the future of the pharmaceutical business?

In early January, Brenton “Brent” Saunders, the chief executive of upstart pharmaceutical giant Actavis, reclined in a medical chair on a stage in an Orlando hotel ballroom as a plastic surgeon pierced his face 30 times, delivering needles full of Botox to the crooks of his eyes and nose and injecting Juvederm Ultra, a dermal filler, into his cheeks. A cameraman documented every prick and projected it on a huge screen behind him. These are bestselling products for Allergan, which Actavis is buying for $67 billion, the biggest health care deal in six years. The audience, 1,000 Allergan sales reps, went wild. “I don’t have any crow’s feet anymore, and I don’t have any wrinkle lines above my nose,” says Saunders, who was boyish-looking even before his face was shot up with treatments. “Now I can say I’m not just the CEO, I’m a user.”

He’s also, at just 44, the hottest executive in the global pharmaceutical business and, at least for now, the undisputed deal king of Wall Street. Five years ago, Saunders had never been a CEO. Now he has run three major drug companies and sold two, generating $25 billion for his public shareholders and investors such as private equity firm Warburg Pincus. In the last year alone, he did deals worth $97 billion. Actavis, a generic-drug maker, was the white knight that saved Allergan from a bitter hostile takeover attempt by rival pharmaceutical company Valeant and activist investor William Ackman. The combined Actavis-Allergan will be the world’s 10th-biggest drug firm, with 30,000 employees and, despite being unprofitable, $8 billion in free cash flow on revenues of $23 billion.

“I interview a lot of people for top jobs,” says Carl Icahn, who backed Saunders for the CEO slot at Forest Labs, which he ran for five months in 2013, and who once promised to bankroll him with $2 billion for a proposed startup. “When I met him, in my mind, he stood out right at the top.” Ackman agrees with Icahn (incredibly, given their bitter history). He calls Saunders “capable and smart”.

Saunders insists that Actavis-Allergan is more than just a short-term trade. It’s the springboard for a revolutionary new kind of drug company: “Growth pharma”, he calls it. Actavis-Allergan will have the scale in marketing and clinical trials of a global powerhouse like Eli Lilly or Bristol-Myers Squibb, but it will eschew the core mission of most drug companies—inventing drugs—preferring to buy them from universities or biotechs all the time. The new company will be the first big pharma that doesn’t even pretend to invent medicines.

“The idea that to play in the big leagues you have to do drug discovery is really a fallacy,” says Saunders. “You have to do research, you have to be committed to innovation. I strongly believe that, but discovery has not returned its cost of capital.”

A drug company that doesn’t even try to make drugs is plain outrageous to some. Sceptics see a roll-up based on tax dodging—run from Parsippany, New Jersey, Actavis has a tax domicile in Ireland—and merger math, led by a neophyte. Saunders’s decision to stop selling a blockbuster Alzheimer’s drug to force patients onto a pricey new formulation didn’t help. It infuriated consumer advocates and was blocked by a federal judge. “One of their first forays as a top 10 company is harming the pharmaceutical industry’s reputation,” says John LaMattina, former head of research at Pfizer.

Meanwhile, investors are cheering. Five years ago, Actavis was a generics company called Watson Pharmaceuticals that had annual sales of $2.5 billion. Since then, it has quintupled sales and delivered shareholders a total return of 545 percent. They know that Saunders may pontificate on the future of pharma, but there’s always a plan B if that doesn’t work out: An even bigger deal.

The son of a urologist and a social worker, Saunders grew up in Pennsylvania and paid his own way through that state’s college system as a furniture mover (he still has a bad back) and a clerk, earning both a JD and an MBA. By 29, he had made partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers, focusing on regulatory compliance in health care.

He might have stayed a consultant for life had he not caught the attention of Fred Hassan, the legendary pharmaceutical turnaround artist. Hassan had made Pharmacia, a Swiss company, into a market darling through a huge acquisition, a spinout and a $64 billion sale to Pfizer. By 2003, when he met Saunders, Hassan was chief executive of Schering-Plough, and many thought the company was unfixable. Schering was accused of kickbacks, dangerously bad manufacturing and illegal marketing.

Hassan needed an outsider to come in and help him clean up. He heard about Saunders from Schering’s chief financial officer, and though there were two other candidates more qualified on paper, Hassan was impressed by the younger man’s drive and focus. “I just became convinced that this guy was going to be all-in,” says Hassan. “In the end, I think all of us have the IQ. The people who look to doing a job as really something they enjoy doing, they are always going to do better than those who look upon it as a job. I said, ‘This guy’s really going to get into it’.”

Hassan sold him to the board of directors as Schering’s new chief compliance officer, and once on board Saunders stamped out bad practices, negotiated hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements with the feds and personally entered the company’s guilty plea. He rose fast: In 2007, Hassan tasked his apprentice with leading the integration of Dutch biotech Organon, which Hassan had bought for $14 billion. In the process, Saunders began internalising Hassan’s dealmaking playbook: Create your own team; eliminate middle managers and pay attention to the people who actually deal with your customers; find products that can be made to perform better. Also: Wrap your strategy up in a nice slogan employees, journalists and investors can get behind—maybe something like “Growth Pharma”.

End result: Schering was sold to Merck for $41 billion in 2009. Hassan left to become a partner at Warburg Pincus, and Saunders was left to manage the integration with Merck from the Schering side. “It’s a tough experience,” says Saunders. “You’ve worked so hard, and you’ve become so passionate for the people and for the way of doing things. All of a sudden there is a new owner, and they want to do things their way.”

When Saunders got another job offer, to be chief operating officer of a health care products company, he called Hassan, his top reference. “Do you have to take it?” Hassan asked. Saunders, taken aback, asked if there was something wrong with his prospective employer. No, Hassan replied, but could he call him back?

Hassan set up a meeting the next day between Saunders and the partners at Warburg. Within a week Hassan’s 40-year-old protégé had an offer to be chief executive of Bausch & Lomb, which Warburg had bought for $4.5 billion in 2007 after its contact lens solution caused dangerous eye infections. Hassan would be chairman.

It was a tough assignment. Bausch was a 160-year-old company that hadn’t grown for 30 years. Saunders replaced two-thirds of the company’s managers. He made a string of acquisitions and introduced 34 new products, including a new laser for eye procedures. In the two years that he ran the firm, sales grew at an annualised 9 percent and Ebitda 17 percent.

Bausch & Lomb prepared for an IPO, with Saunders still at the helm. But then he got a call from Michael Pearson, a former McKinsey consultant, who was now the chief executive of Valeant Pharmaceuticals. They knew each other well from their consulting days. Pearson got right to the point: He wanted to buy Bausch.

Pearson, who declined to comment for this article, had his own philosophy on the drug business—and little respect for many of the people running it. Pharmaceutical companies, he said, spend far too much on both research and marketing, stuck in a model decades behind the times. “When I was a consultant, I’d often have conversations with CEOs in the industry that recognised that much of their R&D spend was not productive,” he scoffed at a 2014 investor conference. “But they feared reducing R&D spend because they thought their stock price would go down.”

By 2008, when he took over Valeant, that formula had been reversed: Cutting R&D meant your stock would go up. This was the absolute nadir for drug research productivity. Despite more than $60 billion spent globally on drug R&D that year, only 18 medicines were approved by the Food & Drug Administration in 2007, the lowest number ever. If you wanted to make money, Pearson reasoned, dump R&D and focus on lower-risk projects and aggressive financial engineering—like merging with a Canadian company with a Barbados tax domicile to lower Valeant’s tax rate to just 5 percent, as he did in 2010.

It was clear Pearson was going to cut Bausch to the bone. (Later, on a conference call announcing the deal, he said Saunders’s team “had made very little cuts” and that Bausch had a cost structure comparable “to a big pharma company”. He promised to cut selling, general and administrative expenses from 40 percent of sales to 20 percent. Once in charge, he did.)

Saunders returned from an IPO road show, went to meet Pearson on a Friday and signed the deal to sell Bausch & Lomb at 4 am on a Saturday. “It was emotional; I poured my heart and soul into Bausch & Lomb,” he says with surprising passion, considering he had spent just 24 months at the firm. “I love the brand. I love the people.

I love the customers. It almost becomes like your second family.” But, he says, it was “the absolute right decision” and there was never any doubt about the outcome. “This company was for sale the day that Warburg Pincus bought it,” he says. “That’s the model in private equity. Warburg Pincus saved this company because this company would have gone through a miserable experience as a public company doing this turnaround.”

As the deal closed, Saunders went from Warburg to Icahn. In 2011, Icahn bought an 11 percent stake in Forest Laboratories and put a lieutenant on the board of directors, convinced that Forest’s 84-year-old CEO Howard Solomon had lost his touch. He chafed at Solomon’s plan to hand the business to his son David. “FOREST LABS IS NOT A DYNASTY TO BE DESPOTICALLY HANDED DOWN FROM FATHER TO SON IGNORING THE GREAT RISK OF THIS ACTION TO ITS SHAREHOLDERS,” Icahn thundered in all caps in a letter to investors

Right after the Bausch deal closed, Saunders was made CEO of Forest to appease Icahn. He quickly dipped into Hassan’s playbook, dubbing the coming shake-up “a rejuvenation”— and almost immediately looking to make a deal. Three months after joining Forest, he was having steaks with Paul Bisaro, the CEO of Actavis, at the JP Morgan Health Care Conference in San Francisco. Saunders joked about the idea of them merging. The idea stuck, and they kept talking about it, more and more seriously.

On February 18, 2014, Actavis bought Forest for $28 billion, a 25 percent premium to the stock’s previous close. Icahn’s take approached $2 billion on the deal. “He came in and he got it done in five months,” says Icahn. “If you look at that result, that’s pretty damn good. I just thought he did a great job.”

Successfully jobless once again, Saunders had dinner with Icahn and suggested starting a company by buying some ageing drugs from a large pharmaceutical company. Icahn offered to give him $2 billion, subject to due diligence. “There are very few people I would do that with,” Icahn says.

But Bisaro, who’d built Actavis into a $6 billion powerhouse in the generic drugs business through his own string of blockbuster deals, also recognised Saunders’s talent. “If he leaves, if we lose him, then the company is going to be worse off,” Bisaro said. Over lunch from Actavis’s cafeteria, he offered Saunders the CEO job of the combined Actavis-Forest, and Saunders accepted. “I know I would probably be able to make more money doing something on my own,” says Saunders. “But I really believe Actavis is something special.”

Of course, one of Saunders’s first moves was, true to his nature, a blockbuster acquisition. On July 11, 2014, just 10 days after he officially became Actavis’s CEO, Saunders asked his board for permission to talk to Allergan’s chief executive, David Pyott, who was embroiled in one of the nastiest takeover battles ever in an industry known for nasty takeover battles.

Pyott had been chief executive of Allergan for 17 years. He’d taken a product Allergan licenced for lazy eye and turned it into Botox (you know what it does), a $2 billion blockbuster. He’d delivered annualised sales growth of 12 percent over 10 years, along with a 267 percent shareholder return. Yet to Valeant’s Pearson, he was an inefficient CEO who allowed bloated spending to drag down shares Pearson offered $45.6 billion for the company, a 31 percent premium for investors over current share prices, and got Pershing Square’s activist hedge fund manager, William Ackman, to take a 9.7 percent stake in Allergan to push the deal through. Pearson’s parsimony was on full display. He opened up an investor presentation by stating that they were in such a nice room only because Ackman covered the cost.

“This’ll never happen again, unless someone else wants to pay,” he said. That extended to his plans for Allergan. He promised to cut Allergan’s $1 billion-plus R&D budget by 69 percent to $300 million and to cut another $1.8 billion, or 40 percent, from the combined company’s operating budget.

Pyott was repulsed. “Valeant is vile, and there is nothing I have learnt since then that has changed my mind,” he says. “They’re an asset stripper.” He did everything he could to fight off the attack. He publicly disparaged Valeant, cut research and development and operational spending himself, and even filed a lawsuit in California alleging that Ackman’s purchase was insider trading.

On July 30, Saunders called Pyott and offered to be a white knight. Over months of phone calls, he portrayed himself as anti-Pearson, despite the fact that he agreed with much of Pearson’s thesis on the drug business. No, Saunders told Pyott, he would not strip the company like Pearson. Allergan would continue to do crucial research on things like dry-eye drugs and successors to Botox. Yes, the business could stay largely intact. They kept talking—six times in October alone. All the while Pearson’s and Saunders’s bids for the company kept climbing, topping $60 billion. Pyott finally agreed to Saunders’s terms when his suit against Ackman went against him. The final offer was $67 billion—far too expensive for Pearson’s blood. Saunders had won.

On the eve of taking over the company, Saunders is saying all the right things to keep peace. For starters, he’s promising to keep Allergan’s R&D budget intact. The new Actavis will spend $1.7 billion, or 7 percent of sales, on R&D, compared with $250 million, or just 3 percent, for Valeant. Saunders even says he plans to keep some research in drug discovery, because Allergan’s research in bacterial toxins (like Botox) and dry-eye disease is some of the best in the world. He points out that when you exclude its generics business, Actavis will spend 13 percent of sales on R&D, about as much as a big pharma. Even when it comes to sales and other operating expenses, he plans to cut only $1.8 billion, or about 20 percent. Ripping deeper, as Valeant would have, has its own costs. Pissing off all your new employees can be expensive and counterproductive. “We’re not the Borg; we don’t go in and assimilate companies,” says Saunders. “We actually try to learn from their culture. We learn from their processes, and we certainly try to learn from their talent. We want to get better.”

Timing plays a part, too. Pearson’s slash-for-cash strategy for Valeant shone for investors at a moment when pharma R&D was at its absolute worst. But last year, 41 new drugs got approved, 130 percent more than in 2007—partly because new science is delivering more successful research programmes and partly because of luck.

Still, Saunders being Saunders, there’s another possibility: A fast sale. The likeliest buyer: Pfizer. Last year, Pfizer attempted a $100 billion hostile takeover of AstraZeneca, in part to avoid paying US taxes by redomiciling in London. It failed. Buying Actavis, analysts have pointed out, would also allow Pfizer to do the same thing.

Moreover, Pfizer has entertained spinning out its generics business, which is composed almost entirely of old Pfizer drugs. Combining it with Actavis would give it a real generics business for that division, while bulking up the drug business, too. In an interview with analysts at Bernstein Research this summer, Pfizer seemed to embrace the idea of potentially buying a generics company. Pfizer declined to comment, and Saunders thinks the prospects of such a deal are “negligible”.

But, of course, the door is open. “Our stock’s for sale every day on the New York Stock Exchange,” he says. “We’re a very shareholder-friendly management and board.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)