The Burmans: Keeping their council

After 114 years the Burmans decided things needed to change at their family-owned Dabur. So every Burman quit his job at the company, and the company has boomed

It was 1998, and Dabur India was in the throes of change. The founding Burman family realised it needed a new strategy for a natural health care and consumer products company that dated to the 19th century.

It generated $209 million in revenue that year, but after going public four years earlier, its market cap was only $179 million. The company had long sold products such as health supplements, hair oil and tooth powder but had diversified into unrelated areas—making chewing gum with a Spanish company, snack foods with an Israeli outfit and cheese with a French partner. So Dabur hired consulting firm McKinsey. And as they fine-tuned the strategy, the consultants posed an uncomfortable question: Just because your last name is Burman, does that make you the most qualified to run the business?

That set the family thinking. It had eight members across the fourth and fifth generations working in different roles at Dabur—and they all quit their executive positions, almost overnight. “It was pretty hard at first,” recalls 78-year-old Vivek Chand Burman, the oldest member of the clan. “We were worried about the future.”

But practicality prevailed. As more Burmans joined Dabur it was getting hard to provide meaningful jobs and easy to create conflicts between different branches of the family. So the decision was made: Professional managers would run Dabur, and no Burman would draw a salary from the company. The reason was simple: You can’t fire family members when they don’t perform. Members would collect their dividends and could build ventures outside Dabur. “We realised that if you want to create a lasting institution and if you want to create wealth, you must have the right people in the right place,” says 63-year-old Anand Burman, fifth-generation scion and Dabur’s non-executive chairman. “We had to have this structure in place to ensure the continuity of the business and the family.”

The family got to work—hiring outside executives, creating a Family Council for family members to get updates on Dabur and discuss their own ventures, and writing a Family Constitution that spelled out everything from succession processes to dividend policies. They also built an office for family members in New Delhi, at a healthy distance from corporate headquarters in Ghaziabad. And a decision was made to distribute 50 percent of the profits as dividends and incentivise the professionals with stock options.

The professionalisation, however, wasn’t exactly smooth from the get-go. The family wasn’t used to not having control. Relations were tense. Then the senior family member who was chaperoning the process, Gyan Burman, died suddenly, and the first outside chief executive, who was working with Gyan, resigned. So Vivek took over as non-executive chairman.

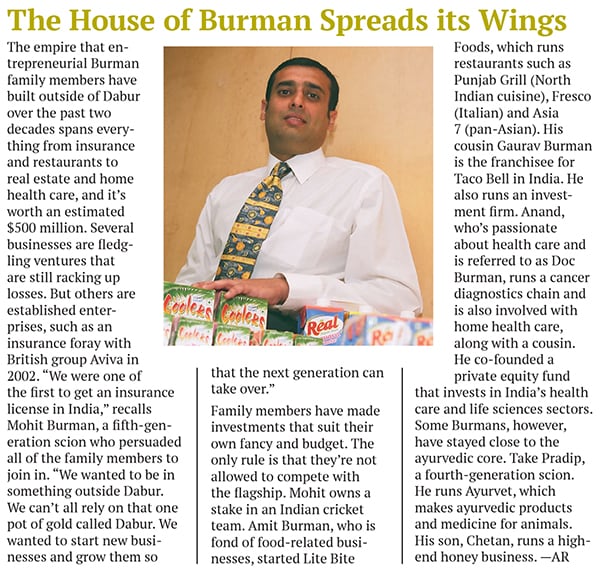

Fast-forward 17 years. Net profits have grown 24-fold, and the market cap has soared 40-fold. Dabur tallied $1.28 billion in revenue and $174 million in net profits for the year ended March 31 and boasts a portfolio of 400 products—ranging from skin-care bleaches and ayurvedic shampoos to natural fruit juices—selling through nearly 6 million outlets across India. The family’s 68 percent holding is valued at $5 billion. Throw in the slew of businesses that members have started on their own (see box, p 119) and Forbes Asia figures that the family’s net worth is $5.5 billion, putting it on our inaugural list of Asia’s wealthiest clans.

“From an Asian perspective this is a unique model,” says Kavil Ramachandran, executive director at the Indian School of Business, who has studied Indian family companies for 15 years. “When you’re in a family business you have employment, perks, visibility, power and status. When it goes away it can lead to a lot of turmoil. The Burmans showed a lot of maturity and realised the benefits early on. They bought the freedom to pursue their own businesses. They’re also maintaining that delicate balance between being strategically involved in Dabur and not interfering with the running of the business.”

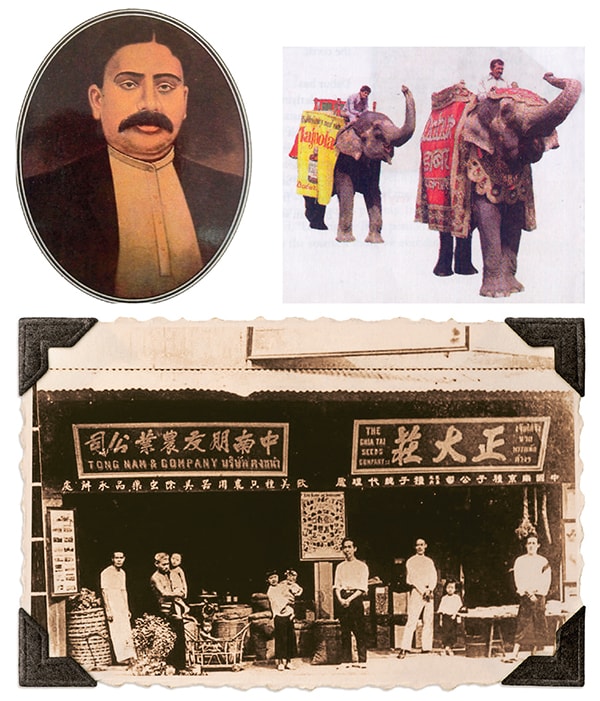

It all began in 1884, when SK Burman, an ayurvedic practitioner, started making medicine in his home in Kolkata for diseases such as cholera and malaria. His reputation grew, and he started a mail-order business, sending medicine to far-flung villages. Dabur still uses some of the ancient Indian texts that describe these formulations. He was fondly referred to as “Daktar” (colloquial for doctor) Burman. The words were later fused to form “Dabur.”

(Clockwise from top left) SK Burman, who founded Dabur in 1884 as an ayurvedic medicine company; elephants promote digestive candies and herbal red tooth powder; an old advertisement for Dabur Amla Hair Oil

The founder’s son, CL Burman, set up the first R&D unit in 1919, expanded manufacturing to two plants and automated medicine-making. In the 1930s and 1940s his two sons, Puran and Ratan Chand, took charge. Puran handled the formulations and manufacturing while Ratan handled sales, distribution and finances. The company entered the hair-oil segment with amla (Indian gooseberry) oil. It’s now among the country’s largest-selling hair oils, with 60 million consumers.

During this time seven families straddling three generations lived in the ancestral home, called Dabur House, in Kolkata, with the business right next door. The families had separate quarters, but there was a common dining room and kitchen. The Burmans had an informal mentoring process to induct each male member into the business under the guidance of an uncle. Ashok Chand Burman (Anand’s father) led the fourth generation and ushered in a new set of traditions—for one, all the boys were enrolled in St Paul’s boarding school in Darjeeling to get a sense of independence. Burmans also started getting degrees in the US. The first was fourth-generation-member Vivek, who earned an undergraduate business degree from the University of Miami in 1960. His three cousins took home degrees from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley.

Once he got back from the US, Vivek pushed for advertising Dabur products on radio and then TV when it was introduced in India. He also started roping in Bollywood film greats to advertise herbal supplements and tonics. The family used its Beechcraft aircraft—with ‘Dabur’ painted on its underbelly—to distribute pamphlets about the products. The day before an aircraft drop—typically during a major fair attended by thousands of people—the company would advertise in local newspapers. Fair-goers would wait for the roar of the aircraft and then collect the pamphlets raining from the skies. The Dabur stall at the fair would quickly get busy. Vivek also used elephants to advertise in the hinterlands. The elephants would walk around draped in banners, advertising digestive tablets and herbal red tooth powder.

Labour unrest perpetually roiled Kolkata, so branches of the family started migrating to New Delhi, and the headquarters moved north in 1972. In 1980 Anand joined the then $31 million-in-revenue Dabur and took it in another new direction. Armed with a PhD in pharmacy from the University of Kansas, he started a pharmaceutical division, using extracts from the Asian yew tree for anti-cancer drugs and other products. He’s now linked to some 40 patents. Meanwhile, his second cousin Amit Burman led the company’s entry into packaged fruit juices under the brand name Real; it’s now a $160 million business.

That’s where the company was when McKinsey came in. After the rocky start with outside management the family tried a new approach. “We gave the professionals the rules and told them what was expected, and we also empowered them with written authorisations from family members to act on their behalf,” says PD Narang, a tax and accounting expert and a non-family member who serves as the liaison between the family and the business. (He’s now a company director.) “We had sufficient controls, and we also had incentives in the form of stock options.”

In 2002 the current CEO, Sunil Duggal, took over. He’s made four acquisitions—taking Dabur into home hygiene, non-herbal skin care and ethnic hair care. He’s beefed up Dabur’s international presence, from Nepal to Europe and the US. A Turkish acquisition strengthened its business in the Middle East and Africa. Foreign sales now make up a third of revenue. “I am sure that if the family had been running the business, we’d never have come up to this level,” says Vivek.

Meanwhile, the Family Council has played an important role in keeping the family involved. There are now 10 seats on the council—held by fourth-, fifth and sixth-generation Burmans—and male family members may join once they turn 25. “When the council started there used to be some personal issues that were discussed, but once we removed ourselves from Dabur there was no discussion on salaries, perquisites, drivers and cars,” says Amit, 46, who’s now Dabur’s vice chairman. “The bickering will start only if someone gets something extra from Dabur. When that’s not the case, what am I going to bicker with anyone about?”

The group meets every quarter, right after Dabur’s results are announced. Family members on Dabur’s board provide an update on the company. After that the council looks at the family’s outside ventures. If members are interested they can invest in each other’s ventures. “There’s healthy competition among all of us—it gives the other family members an impetus to grow,” says Mohit, 46, Vivek’s son and a fifth-generation member who sits on Dabur’s board. “I can’t be sitting in the south of France all year round when my brother and my cousins are growing their businesses.”

What’s striking is that the Family Council is entirely male—no wives, sisters or mothers may join. “Women get married and move into another family,” explains Anand. “Women’s representation is something that’s being debated. We’ll come up with something in the next 24 to 36 months.”

What has worked in Dabur’s favour is that there aren’t too many family members to begin with—just 26. The four family members on the Dabur board represent the two branches of the family—descending from the two grandsons of the founder. The chairmanship is rotated between the different families and is arrived at by consensus. “There’s no secret sauce for keeping the family together,” says Anand. “A lot of us have grown up together in the same house. We get together at every occasion. We like each other’s company.”

But as the next generation takes hold, a new order must be invented because the eight male and female members are spread out from India to the UK and range in age from a few months old to 35. “We need that cohesiveness, and the distance is a challenge,” says Aditya, Anand’s 35-year-old son and the oldest member of the sixth generation. “We need to spend more time with each other because we have so much fun when we get together as a family. We are a mad lot, and we enjoy being that way.”

The extended family gets together for engagements, marriages and milestone birthdays and anniversaries. Meanwhile, Aditya’s generation has no illusions about ever running Dabur. “My grandfather used to tell me, ‘We are running a company, not an employment agency,’” recalls Aditya. “He’d say, ‘If you want to start a company, go and start one. If you want a job, go get one.’” Aditya did. He works with his father building their cancer diagnostics chain, Oncquest Laboratories.

Experts say that while the family has put much effort into staying united, there’s one key factor that has kept the family aloft—Dabur’s performance. It has grown at a torrid pace along with India’s consumer market. And it continues to expand—adding more categories and markets. If Dabur starts performing badly, the family’s unity would be tested. But as Ramachandran from the Indian School of Business puts it: “Families in business need to be introspective constantly. They need to figure out where they are and where they want to go. The business and the social contexts are always changing, and they need to keep reinventing themselves.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)