Venture catalysts: The women who are taking on Silicon Valley's old boys' club

Its weapons, investing and entrepreneurship, provide a blueprint for how to transform any crusty industry from the inside out

1. Jennifer Carolan, Reach Capital 2. Jocelyn Goldfein, Zetta Venture Partners 3. Rebecca Kaden, Union Square Ventures 4. Trae Vassallo, Defy 5. Wayee Chu, Reach Capital 6. Maha Ibrahim, Canaan 7. Kara Nortman, Upfront Ventures 8. Dana Settle, Greycroft 9. Stephanie Palmeri, Uncork Capital 10. Eurie Kim, Forerunner Ventures 11. Theresia Gouw, Aspect Ventures 12. Patricia Nakache, Trinity Ventures 13. Stacey Bishop, Scale Venture Partners 14. Sarah Tavel, Benchmark 15. Jenny Lefcourt, Freestyle Capital 16. Ann Miura-Ko, Floodgate 17. Anu Hariharan, Y Combinator 18. Renata Quintini, Lux Capital 19. Mar Hershenson, Pear VC 20. Shauntel Poulson, Reach Capital 21. Jodi Sherman Jahic, Aligned Partners 22. Leah Busque, Fuel Capital 23. Eva Ho, Fika Ventures 24. Megan Quinn, Spark Capital 25. Aileen Lee, Cowboy Ventures 26. Kirsten Green, Forerunner Ventures 27. Jess Lee, Sequoia Capital 28. Emily Melton, DFJ. Not pictured: Amy Banse, Comcast Ventures; Jennifer Fonstad, Aspect Ventures; Chian Gong, Reach Capital; Dana Grayson, New Enterprise Associates; Nairi Hourdajian, Canaan; Jocelyn Kinsey, DFJ; Katie Rae, the Engine; Kristina Shen, Bessemer Venture Partners | Image by: Jamel Toppin

1. Jennifer Carolan, Reach Capital 2. Jocelyn Goldfein, Zetta Venture Partners 3. Rebecca Kaden, Union Square Ventures 4. Trae Vassallo, Defy 5. Wayee Chu, Reach Capital 6. Maha Ibrahim, Canaan 7. Kara Nortman, Upfront Ventures 8. Dana Settle, Greycroft 9. Stephanie Palmeri, Uncork Capital 10. Eurie Kim, Forerunner Ventures 11. Theresia Gouw, Aspect Ventures 12. Patricia Nakache, Trinity Ventures 13. Stacey Bishop, Scale Venture Partners 14. Sarah Tavel, Benchmark 15. Jenny Lefcourt, Freestyle Capital 16. Ann Miura-Ko, Floodgate 17. Anu Hariharan, Y Combinator 18. Renata Quintini, Lux Capital 19. Mar Hershenson, Pear VC 20. Shauntel Poulson, Reach Capital 21. Jodi Sherman Jahic, Aligned Partners 22. Leah Busque, Fuel Capital 23. Eva Ho, Fika Ventures 24. Megan Quinn, Spark Capital 25. Aileen Lee, Cowboy Ventures 26. Kirsten Green, Forerunner Ventures 27. Jess Lee, Sequoia Capital 28. Emily Melton, DFJ. Not pictured: Amy Banse, Comcast Ventures; Jennifer Fonstad, Aspect Ventures; Chian Gong, Reach Capital; Dana Grayson, New Enterprise Associates; Nairi Hourdajian, Canaan; Jocelyn Kinsey, DFJ; Katie Rae, the Engine; Kristina Shen, Bessemer Venture Partners | Image by: Jamel Toppin Aileen Lee stared at the email in her drafts folder for nearly a month, unsure what to do. The summer of 2017 had been brutal for venture capital (VC). One San Francisco firm, Binary Capital, was evaporating as a partner resigned over allegations of sexual harassment. Accusations of inappropriate sexual advances and affairs would soon lead co-founders of two other prominent firms—500 Startups and multibillion-dollar firm DFJ—to resign. Silicon Valley was facing a reckoning, an early #MeToo moment, months before that scandal radiated out of Hollywood.

Over that July, Lee, a veteran venture capitalist who ranks 97th on this year’s Midas List, made the decision to take a risk. Addressing a note to 23 women she called the “breakfast club”—mostly friends in partner roles at other VC firms—Lee proposed they team up to help women enter the venture industry and rise through the ranks. “Think we all have the same feelings—that the stuff that has recently been highlighted in articles about the gender power dynamic, harassment and the lack of women in VC is just not okay,” she wrote. “We have a window to try and come up with changes for our industry for the better.”

The 48-year-old Lee had paid her dues in venture’s relationship-driven industry, spending 13 years at storied firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers before founding Cowboy Ventures in 2012. Cowboy had only recently broken into the top tier of venture capital and was in the midst of investing its second fund of $60 million. Leading an activist movement could be a business risk. But she decided that if she didn’t speak up then, she never would.

Tech investing is among the most male-dominated industries in America. The number of female partners in venture actually declined following the dotcom bust, falling from 10 percent in 1999 to 6 percent in 2014, according to a Babson College survey. That number has rebounded to about 9 percent today, but at 74 percent of US venture funds, there are no women decision makers; at 53 percent of the largest funds, there are no female investors at all. If Lee’s group could find a way to effect long-term change in this old boy network, it could serve as a model for hidebound industries around the world.

Two startups have already secured funding because of All Raise. Education-savings service CollegeBacker raised $75,000 toward its seed financing thanks to a meeting at the Female Founder event. Agentology, a fast-growing maker of real estate software, raised a $12 million round led by an All Raise member acting on a tip from another. And through a private database of interested female tech leaders—dozens strong and growing—these groups are not just rebutting firms that say they can’t find women; they’re also acting as part of the change.

After months of secrecy, All Raise’s members are going public. When Melinda Gates surveyed the industry to see who had the most promising plans for diversity and inclusion, All Raise caught her eye. The group is in talks with her personal office, Pivotal Ventures, to formalise its support. All Raise has commitments of $2 million from such supporters as Silicon Valley Bank.

Like a startup itself, All Raise faces risk as it builds on early success. Its volunteer members will have to scale carefully and avoid burnout while working within an industry known for its resistance to change. Should they succeed, All Raise’s members have the chance not just to open the eyes of an industry but also to kickstart a transformation of American business, where shockingly only 6 percent of the biggest publicly traded companies are led by women.

At the All Raise February meetup in San Francisco, Medha Agarwal rushes to thank her co-host and fellow venture capitalist Maha Ibrahim, a partner at Canaan who invests out of a $800 million fund.

For more than four hours, Agarwal and 92 other women hear stories from Ibrahim, Aileen Lee, Miura-Ko and others, covering everything from how to speak up in partner meetings to when to switch firms. Agarwal, a midlevel principal at Redpoint Ventures, a $4 billion-in-assets shop in Menlo Park, beams with excitement as she schemes how to replicate All Raise’s network with peers in her more junior role. “All of these senior women have done so much of the heavy lifting for us,” she says.

The struggle to retain women isn’t just a venture problem. In tech, women leave their careers twice as often as men, with 56 percent out by the time they reach a mid-level role, according to a Harvard Business Review report.

In finance, that problem is exacerbated by firms’ struggles to bring new women in. Historically, venture firms have blamed the pipeline problem, infamously articulated by VC billionaire Michael Moritz in 2015: Firms would love to hire women, he argued, but lack qualified female candidates. “What we’re not prepared to do is lower our standards,” he said.

The women at All Raise don’t buy it, and they’re taking action. A work group that includes Miura-Ko and Stephanie Palmeri of Uncork Capital, a firm with $305 million in assets, has built a confidential database of executive women outside of the VC industry who are privately interested in becoming VCs. The work group is also tracking open positions. It has received requests from ten firms already and made 25 introductions to women from the list. “We’re taking away the question that you don’t know who to hire,” says Rebecca Kaden, a partner at Union Square Ventures, the New York firm known for early bets on Tumblr and Twitter.

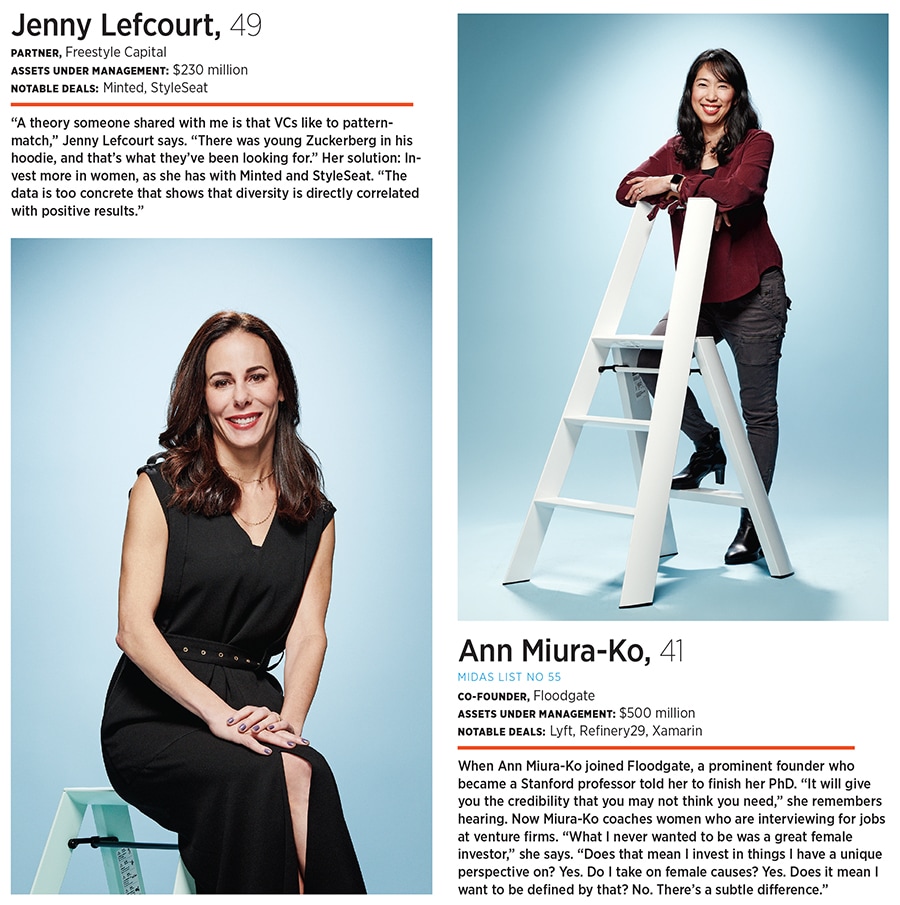

Another way to drive change: Through the customer. McDonald’s didn’t update its menu until patrons voted for healthier options with their dollars, notes Jenny Lefcourt, a partner at Freestyle Capital, a seed-stage firm with $230 million in assets. More recently, public outcry over school shootings pressured Walmart and Dick’s Sporting Goods to change their rules on gun sales.

In venture capital, the customers are the entrepreneurs who take the checks, and All Raise has been quick to seize on their changing priorities. In January, Lefcourt and Aileen Lee began recruiting founders to talk publicly about emphasising diversity when it comes to hiring, boards of directors and funding. Over the week of March 18, more than 400 entrepreneurs flooded social media with matching black-and-white photos declaring their support, including billionaire Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky and Warby Parker co-CEO Neil Blumenthal.

Headspace’s pledge is a warning shot. But All Raise’s partners—capitalists to the core—know that it’s more effective to motivate with greed than with fear. Without a diverse partnership, they argue, investors run the risk of missing out on the next Katrina Lake, the founder and CEO of ecommerce company Stitch Fix. Lake has been lauded for reaching nearly $1 billion in revenue and taking her company public despite raising only $42 million in venture cash, but she says that wasn’t all by design. She would’ve have happily raised more money. Problem was, no one was offering it. Lake says, “Let’s be honest, this was the situation we were forced into, and we made the best of it.”

Women-led businesses are one of the fastest-growing segments of entrepreneurship. Between 2007 and 2016 the number of woman-owned businesses increased by 45 percent, according to an American Express report. But women still have only a small piece of the VC pie. Female-co-founded startups represented only 15 percent of capital raised last year, PitchBook says. In a 2014 Harvard study, men and women pitched the exact same ideas for funding; men were far likelier to get investment offers.

One of All Raise’s solutions is to meet founders earlier and get them support faster. Its most public effort so far has been the popular series Female Founder Office Hours, which matches women entrepreneurs and investors in one-on-one meetings to share startup fears and fundraising tips. Since November, it has hosted events in New York, Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco (twice). At the first two events, more than 800 women signed up for 80 slots. Ursula Mead, founder of North Carolina-based InHerSight, a job-ratings site for women, turned around and made immediate changes to her pitch deck after attending the February Office Hours. “It gives you a lot of confidence that what you’re choosing to include is the right stuff,” she says.

When All Raise’s members first answered Aileen Lee’s call to action, Harvey Weinstein still reigned in Hollywood and Matt Lauer ruled the airwaves at NBC. So as industries like entertainment and media come to terms with their own patterns of harassment and sexism, All Raise has a head start.

In March, members pitched limited partners—the institutions and endowments that invest in VC firms—on creating their own diversity plans. They’re creating Female Founder Office Hours video sessions so founders anywhere can get access to the same support. And in the fall, they hope to host a big conference for women across all venture roles.

For now they’re working after-hours as volunteers, but All Raise will have to evolve in order to last. Burnout is a real concern when people are working what can feel like a second job, something Spark Capital’s Megan Quinn calls a “gender tax”. Enter Silicon Valley Bank and Melinda Gates. With the $2 million already pledged from investors and more in the works, All Raise plans to hire an executive director and full-time staff. A steering committee with defined responsibilities will allow some members, like Aileen Lee and Jess Lee, to direct group efforts and others to take on more casual roles.

As has proved to be the case in other industries, success will be gradual. Forbes contacted 125 partners in 50 male-led venture firms to ask their views about diversity and hiring plans. Most didn’t respond. But leaders from 20 firms did. “While we recognise that not every new general partner will be a diverse candidate, we include a diversity and inclusion review on every discussion of every position,” says billionaire LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman at Greylock Partners.

The women of All Raise are confident that their investing success will speak for itself in a sector driven by financial return. To win, they’re doing it together—a new mentality for women who have, up until the launch of All Raise, largely succeeded alone. “I’m a capitalist. I want to win the best deals. I want my firm to win the best deals,” says Emily Melton, a partner at DFJ. “But other than that I want to also see my female colleagues win and be successful, because I think that helps us all.”

SPECIAL THANKS to TrueBridge Capital Partners of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, for its wisdom and hard work in co-producing the Midas List.

LIST EDITOR: Alex Konrad.

ADDITIONAL REPORTING: Igor Bosilkovski, Biz Carson, Kathleen Chaykowski, Alex Knapp, Samar Marwan.

DATA SOURCE: PitchBook, Dow Jones VentureSource.

Go to FORBES.COM/MIDAS for complete coverage, videos and interviews.

METHODOLOGY: We rank VCs on the number and size of exits over the past five years, with a premium on bolder and early-stage deals. We count only exits above $200 million or private rounds valuing companies at $400 million or more.

Methodology

The Midas List is a data-driven ranking of the world’s 100 top venture capitalists based on all exits (IPOs or acquisitions) above $200 million and private companies valued at $400 million or more over the last five years