How Milk Mantra became the taste of Odisha

With its ethical sourcing model, Milk Mantra has transformed the dairy sector in eastern India, pulling farmers out of poverty along the way

Srikumar Misra, the founder and CEO of Milk Mantra, at the factory in Odisha’s Puri district

Srikumar Misra, the founder and CEO of Milk Mantra, at the factory in Odisha’s Puri district

On the busy streets of Bhubaneswar, Milk Mantra’s lemon green hoardings stand out. A cow with big, round eyes stares out at passersby, her eyes forming the Os in ‘Milky Moo’, the name by which the company sells its produce.

An auto driver who moonlights as a freelance photographer in Odisha’s capital city says Milky Moo’s quality is much better than OmFed, the state’s co-operative dairy company. “In OmFed, they only put powder,” he says. After a slight pause, he adds: “Milky Moo must also be putting powder in their milk, but not that much. It’s fresh and tasty. It’s only a little more expensive, but it’s better for our children.”

Milk Mantra boasts of this superior quality loud and clear: The advertisements highlight there’s “no need to boil” the milk, a compulsive practice among Indians who believe it kills bacteria.

To find out what makes Milk Mantra’s milk and milk products, including curd, buttermilk and paneer, better—so much so that the company went from turning ₹18 crore in revenue its first year of operations in 2012 to ₹182 crore in the last fiscal—Forbes India travelled to the source.

Heading eastwards to Puri and beyond, as the bustle of Bhubaneswar gives way to sparser buildings and more open fields, Milk Mantra’s branding is still hard to miss. On bus stop hoardings and kirana stores splashes of lemon green dominate. OmFed’s weathered milk booths, on the other hand, are scattered and barely visible.

Forty-five kilometres away from Puri, village huts with thatched roofs dot the landscape. It is in these villages that Milk Mantra sources its milk directly from farmers. Small farmers with marginal land holdings and a handful of cattle line up with buckets of milk at the nearest Milk Mantra collection point to have their milk tested for its fat content. Every 10 days, the farmers receive their payments—about ₹25-29 per litre, depending on the quality. A chart pinned up at every collection centre spells out the prices of milk per litre based on the percentage of fat. This transparency, as well as the elimination of middlemen, ensures that farmers receive fair and full prices.

“The best thing about Milk Mantra is that we are paid well and on time,” Premananda Lanka, 65, a farmer, says in Odiya, as he squeezes the udders of one of his six cows. His two grandchildren romp about while his daughter-in-law chimes in, “Our family income has risen. We save about ₹2,000 a month, enough to buy groceries for the whole family.” They also reserve a portion of the milk for themselves, giving it to the children, while also making ghee and curd for the family, both luxuries in rural households.

For another lady who singularly runs her household, her sole cow is a means to financial independence. She shows off the animal her grazing in a shed. She bought it on her own steam, she says, and now with the money she earns, she plans on taking a loan to buy another.

Not only has Milk Mantra tied up with banks to provide low-interest loans to farmers to purchase cows, but it also provides better feed at market rates. Besides, it has vets on call to help farmers breed healthier cows and regularly conducts health camps in villages where farmers can bring their cows for check-ups. Milk production has since tripled.

*****

For Srikumar Misra, the founder and CEO of Milk Mantra, it’s all very simple. ‘Happy Farmers = Happy Cows = Best Milk’, reads the company slogan, plastered all over the company headquarters in Bhubaneswar. “I wanted to create a B2C brand that was premium, differentiated and scalable. And ethical sourcing of milk had to be at the heart of it,” says the 41-year-old.

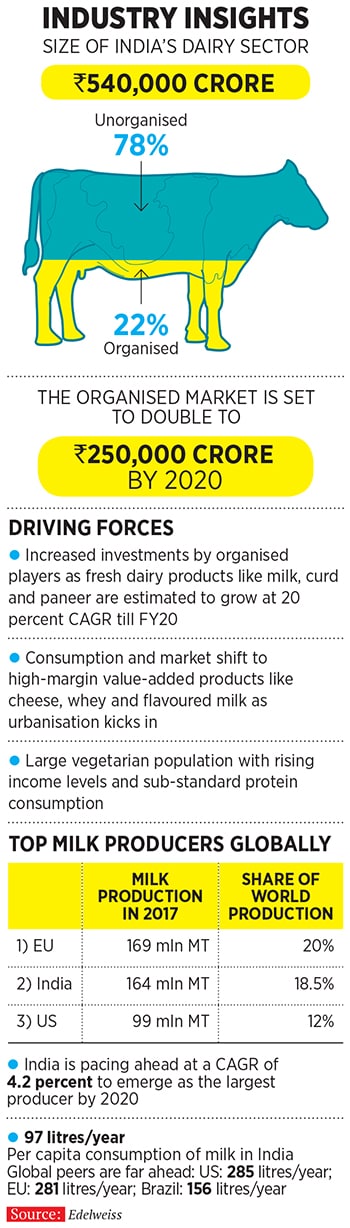

They liked the idea and saw a market opportunity: India’s milk consumption, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5 percent between 1992 and 2015, was outstripping its milk production growth of 4 percent CAGR. Moreover, the per capita consumption of milk in the East was—and continues to be—the lowest compared to the rest of the country, according to industry experts. The North dominates followed by the West and South.

One reason for this is the “trust deficit” that exists among consumers for perishable items like milk. Since the organised procurement of milk in eastern India stands at 10 percent compared to the national average of 23, says Misra, milk is often thought to be adulterated or stale.

Clearly an increase in productivity—Indian cows produce 8-10 litres of milk a day versus the global average of 30-35 litres—and overcoming this lack of trust through the “ethical sourcing model” Misra had drawn up, would close the demand-supply gap. “But investors had never funded an agri-food business before, let alone one in Odisha. It was nowhere on their radar. The only companies being backed at the time were ecommerce ones,” says Misra of the time in 2009.

After two years of pitching unsuccessfully to venture capitalists, Misra decided to turn to individual angel investors who were willing to offer him amounts ranging from ₹5 lakh to ₹60 lakh. He bandied together a number of them, raised the seed amount he needed and kicked off operations in 2011.

Shortly after, Vineet Rai of impact investment fund Aavishkaar Venture Management, bought into Misra’s vision and put in ₹5 crore into the company. “Capital would generally never go there to create a dairy,” says Rai because the tilling of land or animal husbandry wasn’t commonplace in the rural regions of Odisha. “But the demand for good quality, packaged milk was clearly there.” Plus Misra’s experience of growing consumer foods brands in emerging markets like South Africa, Turkey, China and eastern Europe with the Tata group was an added advantage.

What began with a handful of farmers and a single collection point has today morphed into a network of 55,000 farmers spread across the eastern and western regions of the state, a daily collection of over 1 lakh litres through 390 collection centres and distribution spanning Odisha (for milk and milk products) as well as Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal (for milk products).

Along the way, the company has raised four rounds of funding totalling ₹150 crore. While Aavishkaar further upped its stake, other investors like Eight Roads Venture (formerly Fidelity Growth Partners) and Neev Fund also swooped in. “The fact that we were able to attract mainstream investors, like Eight Roads and Neev, is testimony to the strength of our business,” says Misra.

*****

At the outset, packaging innovations were part of Milk Mantra’s pitch. Misra knew from experience that the transparent plastic pouches that packaged milk was generally sold in exposed the milk to sunlight, turning it rancid. So he came up with a three-layered design—an inner translucent film to be in contact with the milk, a black middle layer to block out the sun and an outer white layer complete with Milky Moo design elements—which increased the shelf life of Milk Mantra’s packaged milk by four days.

Farmers gather at Milk Mantra’s collection centre at Kanti village in Puri district

Farmers gather at Milk Mantra’s collection centre at Kanti village in Puri district “People say milk is a commodity and milk products are value-added items, but the distinction bothers me,” says Misra. “Our milk is of a high quality. People recognise that because of which we are able to charge a premium. Our milk is value-added,” he stresses, adding that Milk Mantra charges a “mass premium” of 10-20 percent on its packaged milk over competition. “The minute you price it at a 30 percent premium, the product becomes niche and difficult to scale,” he says.

In fact, Milk Mantra’s gross margins of around 20 percent on packaged milk are higher than the industry average of 15-18 percent. Complete control over the supply chain and the elimination of middlemen help keep costs down, says Debashish Mohanty, head of quality at Milk Mantra. On milk products like curd and buttermilk, the company’s margins of 28-35 percent are in line with the sector. However, on products like flavoured yoghurt, margins are as high as 40 percent, says Mohanty.

But while the business of fresh dairy is regional—given milk’s perishable nature—and local players dominate, the dairy products business is difficult and competition is intense. Earlier this year, French food giant Danone exited its India dairy business after seven years of trying to make headway. FMCG behemoth Britannia also hasn’t made much of a dent. Despite two decades of effort, dairy products continue to account for less than 5 percent of total sales. According to Edelweiss analyst Shradha Sheth, companies that don’t have the infrastructure for direct milk procurement are at a disadvantage. “Players that procure milk directly from farmers enjoy a huge competitive edge as it assures steady milk supply and consistency in milk quality,” she says.

As a result, players that have this infrastructure in place, like the listed, Navi Mumbai-headquartered Prabhat Dairy that has traditionally focussed on B2B sales, have sniffed an opportunity. With milk products commanding higher margins than fresh milk, the company is looking to up its share of B2C dairy product sales from about 26 percent of revenues currently to 45 percent by FY20. Similarly, while frontrunner Amul already has a strong pan-India presence, other players like Mother Dairy, Parag Milk Foods with established brands like Gowardhan and Go, Heritage and Kwality are beefing up their B2C sales of dairy products, adds Sheth.

“Getting shelf space [for dairy products] is not easy. Milk Mantra has done well so far given its localised focus. But to now scale up, it will need a focussed strategy. Brand building, product innovation and a strong distribution network will be at the heart of it,” says brand expert N Chandramouli.

Even as competition is nipping at its heels, Misra remains unperturbed. He’s looking to scale the company—which turned Ebitda-positive six months ago—to ₹650 crore over the next four years; inorganic growth will be part of it. Says Mishra, “Demand for a good quality product will always be there.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)