Stagnation, losses: Why the economics of startups need a fundamental reset

With investor sentiment turning sour, startups are being forced to cut costs, find new revenue streams and focus on profitability

High quality startups will still raise funds now.

Image: Shutterstock

High quality startups will still raise funds now.

Image: Shutterstock

In what Aadit Palicha describes as a “terrible investing market”, Zepto, the speedy delivery startup he co-founded two years ago, managed to raise $200 million at a $1.4 billion valuation, making it India’s first unicorn of 2023.

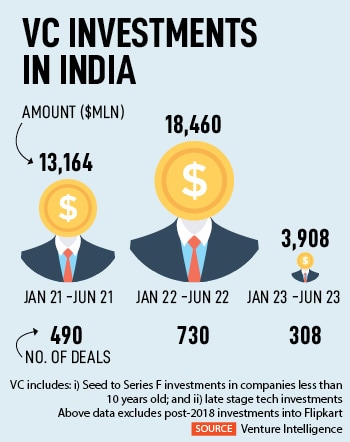

Since the onset of the so-called “funding winter” roughly 20 months ago, Indian startups have been struggling to raise funds. They raised just $3.9 billion in the first half of 2023, 78 percent lower than the same period of last year, according to data provider Venture Intelligence. The funds were raised by only 308 startups, compared with 730 startups in the same period last year.

At this run rate, startups may end up raising less than $10 billion this year, a far cry from the record $30 billion garnered in 2021 and $20 billion in 2022.

“High quality startups will still raise funds,” says Pankaj Makkar, managing director at Bertelsmann India Investments, which has backed companies like Licious, Pepperfry and Lendingkart. By “high quality” he means those that are run efficiently with an eye on unit economics, profitability and cash reserves. Palicha, for example, spoke of “real stores” that are generating “real cash” in an earlier interview with Forbes India. Zepto uses a network of dark stores or small warehouses to deliver goods within 20 minutes of a customer placing an order. Annualised revenues now stand at $600-$700 million compared to around $20 million in FY22.

A Meesho rival says, “In this business it’s easy to give incentives, book your revenue for the next three months and then claim that you are profitable.” Meesho didn’t respond to Forbes India’s request for comment.

A Meesho rival says, “In this business it’s easy to give incentives, book your revenue for the next three months and then claim that you are profitable.” Meesho didn’t respond to Forbes India’s request for comment.