Music: Sounds of souls in Rajasthan's Ahhichatragarh Fort

With its serene atmosphere and intimate performance spaces, the centuries-old Ahhichatragarh Fort plays the perfect host to the Sacred Spirit Festival

The Areej Sufi Ensemble from the Sultanate of Oman performing at the Sacred Spirit Festival

The Areej Sufi Ensemble from the Sultanate of Oman performing at the Sacred Spirit FestivalImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

Some two hours after touching down at Jodhpur airport in mid-February, I found myself at the gates of the Ahhichatragarh Fort, after making my way through the helter-skelter of Nagaur, a rather unremarkable town. Located halfway between Jodhpur and Bikaner, Nagaur is a typical old Indian town confused about its place in the modern world—it is choked with vehicles, shops and loudspeakers blaring everything from calls to prayer to sub-bass-pumping Bollywood hits. But although chaos engulfed the fort from all quarters, inside was a whole other world altogether.

Row upon row of white tents were set within the sand-and-stone acreage of the 12th century fortress, looking like a luxe barracks: Each tent was outfitted with a double bed, heater, floor fan, converted electric ‘laltains’ and a bathroom with running hot water and toiletries by a luxury ayurvedic brand. Traditional Rajasthani designs and motifs brightened up the otherwise staid safari tents, lending a local touch to the bedspread, durries and curtains.

As I set off on a walkabout around the property, scaled a flight of stairs to the ramparts and circumambulated the site, the contrast between the chaos outside the fortress walls and the serenity within became stark.

Ahhichatragarh Fort abounds in peelu trees, also called peelo vajradanti or toothbrush trees because of their twigs that are used to make natural teeth cleaners known as miswaak. Their cascading willow-esque leaves provide an effective camouflage for the posses of parakeets hiding within, who erupt in cacophonous union, scattering skyward at the slightest disturbance. From atop the bulwarks I got a bird’s-eye view of the durbari halls, courtyards and mini mahals interjected by water channels, fountains and baths, beautiful even in their waterless state.

South Korean experimental pair Duo Bud

South Korean experimental pair Duo BudImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

But the fort wasn’t always this pristine. But by the 1980s it had fallen into considerable disrepair after years of neglect. The Mehrangarh Museum Trust (MMT), which also presides over the care and maintenance of Jodhpur’s celebrated Mehrangarh Fort, set about a long and extensive restoration project along with a couple of generous patrons. Grants from the Los Angeles-based Getty Foundation and the London-based Helen Hamlyn Trust, along with contributions from MMT itself, resulted in the resurrection of the fort’s architectural splendour more than two decades later.

By which time someone had the bright idea of using this relatively unknown but exquisite fort to host a yearly music festival. Evidently, the British pop star Sting had a role to play in the conception of what eventually became known as the Sacred Spirit Festival (he has attended but not performed at the festival yet). In its 13th year now, the festival has seen spiritual and classical musicians from India and around the world grace and uplift the air within these magnificent stone walls.

The Nagaur fort houses 200 tents on its premises

The Nagaur fort houses 200 tents on its premisesImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

What began in 2007 as a single venue for a select audience turned into a two-city spectacle, with Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort being added as a second staging ground four years later. The reason was to open up the festival to a larger audience of international visitors and music lovers from India without giving up the intimate exclusivity of its original creation. Nagaur continues to remain small and contained. Only those residing within the fort, in one of the 200 tents or 30 rooms, have access to the music. So devoted are many of its long-time guests that the event sells out two years in advance. And you can’t just buy a ticket. You have to know the right people to find your way in.

*****

This year boasted a fabulous line-up of artistes from Africa, the Middle East, Asia and India. Over three days and five stages, 13 acts played for a delighted audience, with many of the artistes giving the eager aficionados more than one performance, occasionally spontaneous and unscheduled in some quiet corner of the fort. Eschewing a current festival trend, no performance at any stage overlaps with another; there’s plenty of time to move from one stage to the next, sometimes to grab a drink, a meal or even a short snooze, so you never have to miss out on any of the music. The stages were all relatively small, the lighting never overwhelming and the performances easy and personal.

Morocco’s Walid ben Selim singing lyrics by revered Arab poets

Morocco’s Walid ben Selim singing lyrics by revered Arab poetsImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

Every day’s recitals were unique. Some were held under a gorgeous peelu tree in the mornings, as when Morocco’s Walid ben Selim beautifully intoned the lyrics of revered Arab poets like Hallaj, Ibn Arabi, Abu Nawas and Mahmoud Darwich as China’s Jiang Nan plucked surreal tones from her 21-stringed harp-like instrument known as guzheng. Others upped the visual drama a notch, like when the Tibetan singer Loten Namling and his collaborators, Ustad Daood Khan Sadozai from Afghanistan and a troupe of spirited Manganiyars, performed against the backdrop of Buddha’s countenance-in-repose projected on a fortress wall. The sounds of the sarangi, sarod, khartal and Namling’s large voice recounting the glories of Milarepa under a nearly full moon-lit sky were ethereal.

The sunset concerts were no less divine. Artistes like bansuri virtuoso Rakesh Chaurasia and the South Korean experimental pair known as Duo Bud enthralled and entertained the audience as the day gave way to night. It was the magic hour when we were reminded not to take the daytime heat for granted; those desert nights can get pretty cold.

Tibetan singer Loten Namling and his collabora-tors

Tibetan singer Loten Namling and his collabora-torsImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

The Areej Sufi Ensemble from the Sultanate of Oman were visually as much a treat as they were sonically, as they swayed in harmonious (and costumed) symmetry while extolling the Creator through impassioned calls and responses. And when Senegal’s Sheikh Djimbira Sow began to sing, his vocal prowess, timbre and style reminded me of his fellow countryman, the great Youssou N’Dour, as the trio of drummers behind him wrought infectious West African grooves and tones out of wood and skin. Which led me to think: Wouldn’t it be a real treat if Sting were to reunite with past collaborator N’Dour at a future festival?

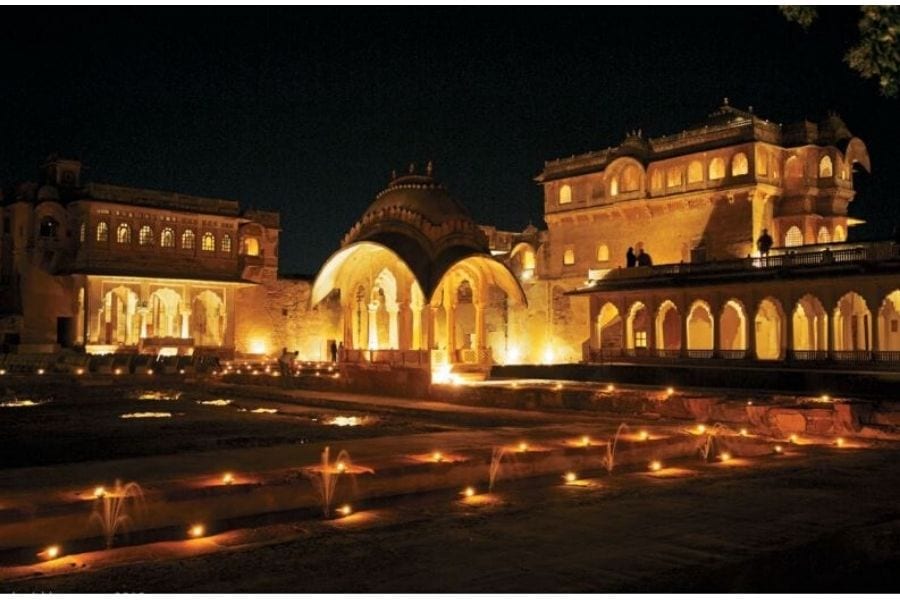

Each night’s performance would end at the theatre of a hundred diyas (or perhaps a few hundred), at the sublimely lit Deepak Mahal, situated in a discreet corner of the fort. Danish Hussain Badayuni’s ecstatic qawwalis and Kachra Khan Manganiyar’s virtuosic renditions of Rajasthani musical lore could not have had a more romantic setting, though their words of love were directed not to human individuals but to the incorporeal and divine. Other performers at the festival included Iran’s Mohammed Motamedi, as well as Sufi poetry expert Madan Gopal Singh, ghazal exponent Kavita Seth, Rajasthani devotional singer Mir Mukhtiyar Ali and Kashmir’s Farooq Ahmad Ganie, all from India.

The Ahhich-atragarh Fort was renovated in the 1980s by the Mehrangarh Museum Trust

The Ahhich-atragarh Fort was renovated in the 1980s by the Mehrangarh Museum TrustImage: Neil Greentree/Mehrangarh Museum Trust

As with any festival of note, it was not only about the music. The breakfast tents and courtyard dinners provided meeting places and watering holes for old friends to reunite even as new bonds were made. Three days of cohabitation inevitably led to a familiarity of faces, as musicians mingled informally with their audience between performances. And though the crowd was rarefied and cloistered, away from the helter skelter of the outside world, the festival includes the local populace in a variety of ways. Artisans from the area have long been employed in the fort’s restoration works. This year they went further, formalising that relationship with the craftspeople of the region by launching their own brand of textiles, clothes and jewellery, named Nagori in tribute to the town’s history, which dates back to the Nagavanshi Kshatriyas, snake-worshipping warriors of medieval times who once reigned over the region.

Three days of spiritual music in the desert did not mark the end of it. After this leg was done, the festival shifted for another three days to the more grandiose Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur. For me, though, Nagaur was truly special, its smaller scale vastly more endearing than the opulence of a large, imposing venue. This intimacy of musical experience and soul connection far outweighs the scale of any big festival, no matter how high the fortress walls or impressive the marquee names. The more I think about it, the more I realise I might just become one of its devoted repeat visitors.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

0405_s.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)