Root Value: Kerala's Narippatta Raju shows village theatre is alive as ever

Narippatta Raju's theatre stays as connected to its rural vision today as it had when he started out

A performance of the 1984 play Kudukka

A performance of the 1984 play KudukkaImage: Narippatta Raju

Completing more than four decades in an unforgiving profession is an achievement. For sexagenarian Narippatta Raju, stalwart of Kerala theatre, it has been a journey that has placed great demands on his creative and personal resources, with equally gratifying pay-offs.

Known for his work in the countryside—quite literally the grassroots—Raju’s directorial output remains as prolific as ever. This year will see the release of a volume of writings on his career, as well as the inauguration of a theatre school for younger actors in his name. Both these endeavours will take place under the aegis of Natyasasthra, the theatre group in the hamlet of Katampazhipuram, which has been his stamping ground for some 20 years now.

Less than an hour’s ride away, Raju’s ancestral home is in the remote village of Karalmanna in Kerala’s Palakkad district. Despite its seclusion, it is an important landmark on the state’s cultural map, as a cradle for Kathakali that has produced several exponents of the form, including the well-regarded Narippatta Narayanan Namboodiri, who is Raju’s brother.

Raju’s was a culturally rooted family that was also typically middle-class. “Although my parents would never negate my interest in the arts, they would have preferred it if I had chosen a conventional line of work, like engineering,” remembers Raju. His joining the University of Calicut’s School of Drama in Thrissur was an act of rebellion.

The institute opened in 1977 in the suburb of Aranattukara, and Raju was a student of acting in what was only its third batch. He had received some early training in Kathakali and Bharatanatyam, but what he considered “the limiting baggage of traditional forms” also allowed him to enter modern theatre much more fluidly. “The grounding opened up new possibilities even in the contemporary idiom,” says Raju.

As it was for the entire country, the late 1970s was a transitional period for Kerala. Fired with the idealism rife in a post-Emergency milieu, theatre had become an indelible part of political activism. One of Raju’s contemporaries was the late Jose Chiramel, from the drama school’s first batch, whose stature in Malayalam theatre has become almost legendary.

Along with their cohorts, they took theatre out into the rural outback, setting up camps in villages for workshops that sought to harness not just the radical young intelligentsia of the 1980s but also scores of ordinary people. “It was a period of intense learning, which could be compared to a residency that a medical student might undergo,” says Raju of those pioneering days.

Theatre’s power as an agent of change was never more manifest. One of Raju’s formative influences was Maya Tangberg-Grischin, the accomplished Swiss theatre-maker who conducted workshops at the drama school in the 1980s. Her assimilation of local traditions into her own performative grammar can be traced to the writings of two European theatre greats, Jerzy Grotowski and his protégé Eugenio Barba. The two studied Eastern theatre forms like Kathakali in the 1960s, much before the “theatre of roots” movement took wing in India in the mid-1970s, spearheaded by the likes of Habib Tanvir, Ratan Thiyam and, in Kerala, Kavalam Narayana Panicker.

Raju has immense respect for Panicker: “He had a deep knowledge of traditions, folklore, and classical forms.” He characterises his own oeuvre as forged in the spirit of the classical form, but not the form itself, unlike Panicker’s style. Raju is much more dismissive of the tribe of imitators that his great predecessor spawned. “They lack Kavalam’s integrity of approach, which is why they have been harmful for Malayalam theatre,” he adds.

******

Raju’s own professional engagement with theatre direction took off in full earnest only in the early 1990s after he returned to India, having spent four-odd years in Finland, under Tangberg-Grischin’s guidance. Luminaries like G Sankara Pillai (who founded the Thrissur School of Drama) had irrevocably shaped his world view, and despite being employed as an educator at his alma mater since graduation, he had grown wary of urban theatre.

“When I arrived at Karalmanna in 1993, I knew what I was going to do there,” he says. “If you want to develop theatre culture then you must work in rural areas.” Since the 1940s, Kerala’s prodigiously successful library movement—instrumental in establishing universal literacy in the state by the 1990s—had engendered a cognitive spirit in innumerable rural communities. At the local reading room, Raju was able to channelise the energy of youth gatherings into an invigorating theatre subculture.

Unlike, say, Tanvir’s works with Chhattisgarhi tribals, Raju’s projects were smaller in scale and brought under its net largely literate folk who were also agrarian wage-earners, hence possessing the lithe physicality that lent itself naturally to theatre. “I never tried to train them with theatre exercises. They had fantastic instincts. If I explained a characterisation with parallels connected to their lives, it yielded immediate results,” explains Raju.

Although he was able to draw unfettered performances, the initial years were exhausting since he had to manage all areas of production—from costumes to lights to make-up—by himself. By the mid-nineties, he had already come to be regarded as an authority on stage-lighting, imbuing traditional Koodiyattam and Kathakali performances with contemporary illumination. And, since his scratch repertory was available only for portions of the year, Raju took up directorial projects elsewhere, building a name for himself as a director of note.

Vaaye Paathalam (1993) was a dramatisation of the 1984 novel by UA Khader

Vaaye Paathalam (1993) was a dramatisation of the 1984 novel by UA KhaderImage: Narippatta Raju

While he mounted several short plays with his own village troupe, which toured the interiors of Kerala extensively, those years also saw a slew of critically acclaimed productions such as Vaaye Paathalam (1993), the dramatisation of the 1984 novel by UA Khader; Edasseri Govindan Nair’s Kuttukrishi (1997); and Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun adapted into Malayalam as Pakalonetire Pallivetta (1999). Most of his plays were in Malayalam, but a stint in Hyderabad saw him take on several plays in Telugu, and he directed the Sanskrit play, Venisamharam, by Bhattnarayan Kavi for the drama school, where he continued to teach.

******

It was circa 2000 when Raju began a new prolific phase in his career, in close association with G Dileepan, his childhood friend and a professor of English and Sanskrit who had founded Natyasasthra in 1996. Raju, now the group’s artistic director, was able to bring his technical and practical expertise to a collective with rich literary antecedents. “From then on, I have never needed to worry about organisational issues. Dileepan did that. I could focus on the artistic aspects of a production,” he says.

Natyasasthra’s sensibility had been less rural-oriented, and they had staged sophisticated productions in towns and cities. Raju’s experiments in Karalmanna were repeated in several villages, with theatre groups mushrooming as ancillary units to reading rooms. “Maybe I can say I was extending my work to other rural areas,” he observes. One of his earliest productions with Natyasasthra was a staging of Manjula Padmanabhan’s Harvest (2000). His one lament is that the plays that he staged with the group remain unpublished, including the translation of Padmanabhan’s award-winning work.

Observers like historian Renu Ramanath speak of a noticeable change in approach in Raju’s work (after the association with Natyasasthra began): “More than the spectacle of performance, he appears to focus his energies on actor training. He is able to mould actors like no one else I have seen.” His workshops, which Ramanath likens to ‘actor labs’, are characteristically inclusive, welcoming everyone from children to 50-year-olds, even as he goes about igniting the passion for acting in them.

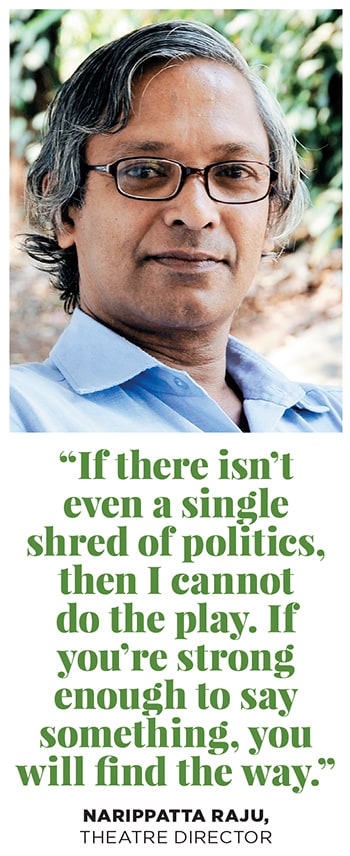

Raju was one of the earliest practitioners to ‘break’ the proscenium with his open-air stagings, which employed the panchabhuta (five ingredients) of live performance—fire, air, earth, water and aromas—long before the current crop of theatre-makers took over the idiom. Although aesthetics are important, what matters most is the thematic focus of a play. “If there isn’t even a single shred of politics, then I cannot do the play,” he says.

The causes that he holds close are the upliftment of rural people, the class struggle, and the empowerment of women. Yet, in his plays, the underlying agenda is never spelled out explicitly. It is instead integrated into a play’s narrative in the form of undercurrents and ambiguities that might provoke reactions in those receiving the plays.

He mentions his 2006 production of Panicker’s Kalivesham, the famous Kathakali play in which an actor, Nata, is predestined to play Kali, the evil character that he is possessed by. The peripheral part of Nata’s wife becomes a protagonist in her own right in Raju’s version. As he says, “If you’re strong enough to say something, you will find the way.” One of his most recent works is the unrelentingly text-heavy Theeyoor Rekhakal (2016), the dramatisation of the novel by N Prabhakaran.

Despite being regularly staged at national festivals in recent years, Raju’s works have not been discovered by audiences outside Kerala—such being the constraint of language in a country of myriad tongues—but his career is filled with lessons that are valuable to theatre-makers everywhere.