The hunt for green data

As agri-tech ventures rise fast and go deep to solve problems, what are the implications of data harvests for farmers in India?

We have got more than 4 million missed calls on the platform. That’s helping us get data because they are posting specific questions. We have a call centre with more than 150 people, many of whom are farm experts.”

They call him Thiru. Thirukumaran Nagarajan is 34 and sports a beard. Some years ago, the engineer-MBA grad ventured to explore the ocean we call the internet. Steering and navigating an online business through waves of real-time data are to the 21st century, what whaling was to the mid-19th century: Essential and immensely profitable for those who take to the sea first.Shardul Sheth, CEO, Agrostar

It didn’t work out for Thiru in his late 20s. “His confidence had taken a bit of a beating. But I liked the way he had built it,” says Raghunandan G, co-founder of TaxiForSure (TFS), who hired him in 2014. “It was too early, but the way he thought of the business and built the team was impressive.” Thiru became TFS’s head of mobile products before a bigger fish, Ola, swallowed the cab aggregator.

Thereafter, he ventured into another bloody sea, online groceries, with two of his TFS mates. They didn’t know the voyage would require them to take farmers on board someday. That wasn’t the plan.

Thiru’s new outfit was named NinjaCart, with Raghunandan as angel investor. The founders had built a location-based instant messaging platform for shopkeepers. They used it to link urban customers with kirana or small shops in a sector that had BigBasket, Grofers and PepperTap headlining a clutch of online grocery apps. In 2015, capital was flowing. And the online grocery cannons were firing discounts indiscriminately to attract customers.

Shopkeepers now became customers. And farmers became the suppliers. Their online product would help small shopkeepers in cities procure fruits and vegetables from farmers. NinjaCart would deliver.

That’s how an agri-tech company was born. NinjaCart is present in Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad, with plans to expand to Mumbai and Delhi-NCR, even as Reliance—with a national brick-and-mortar retail business—recently articulated its ambition to take ecommerce to India’s hinterland. Maybe, there’ll be another price war. Thiru is rarely content, but feels NinjaCart has thus far aligned three goals for farmers and shopkeepers alike: Improve prices, provide reliability and convenience.

This requires buying and selling vegetables in 24-hour cycles. “It is about (managing) volumes,” says the soft-spoken CEO of NinjaCart in Bengaluru. “It was easy to grow from procuring and delivering 10-20 tonnes of fruits and vegetables. But doing 300 tonnes without any mistake is the most critical job. So we have built technology to manage inventory; algorithms and software programs to manage drivers and warehouses.”

Thirukumaran Nagarajan, Co-founder & CEO, NinjaCart

It has an active base of 5,000 shopkeepers, who procure fruits and vegetables from 3,500 farmers in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Knowing consumption patterns of shopkeepers, while knowing which farmer is growing what crop(s) is a powerful lever. Such data can influence farmers’ decisions, like what type of vegetable could have more demand in the market, when to sow, when to harvest, etc.

Quietly, in the past three years, a variety of agri-tech ventures have been generating such data in India. Even as online services like NinjaCart benefit the farmer, agri-tech has begun to interest larger global players—greater sums of capital. In December 2018, NinjaCart announced its second round of capital: $28 million, apart from $5 million in venture debt. This featured the venture funding arm of global agrochemicals and seeds company Syngenta. The company’s investors also included Accel Partners, Qualcomm Ventures, and Nandan Nilekani’s NRJN Family Trust among others, who are part of NinjaCart since its first funding round in 2016.

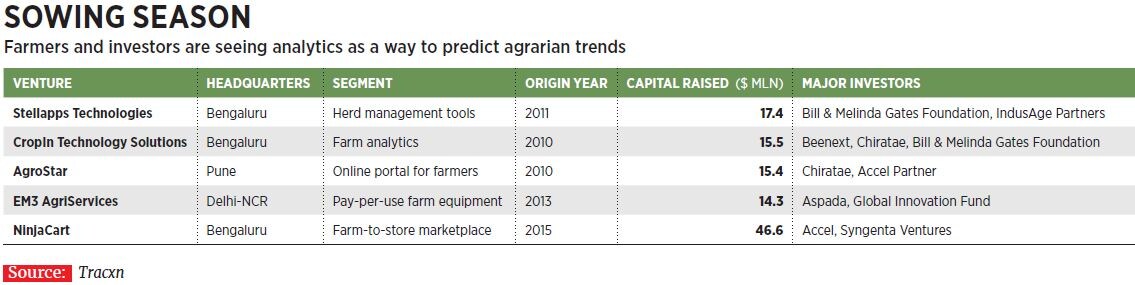

In the past six years, at least $130 million of venture capital has gone into nine homegrown agri-tech ventures. For India’s primary occupation familiar with revolutions in maximising wheat and rice production (in the 1960s), and milk (Operation Flood in the 1970s), coders have now pried opened opportunities to apply software, harness data and solve logistical challenges in agriculture. What are the implications of a data boom for the sector? For now, it’s a growing quantum of capital chasing data aggregators.

Global Appetite

Software has already helped bypass a couple of erstwhile Indian realities by finding ways to link supply with demand. This is the original promise of the information highway. In previous eras, progress and scalability in agriculture depended on policy. As a result, “the biggest reforms took place after a bad crisis”, said agriculture economist Dr Ashok Gulati at the Bengaluru Tech Summit in November 2018. “Policy-induced solutions have driven agriculture revolutions. As a result if there are 40 solutions, only two (could) scale up,” added the professor for agriculture, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. The internet has changed this reality.

Krishna Kumar, co-founder & CEO, Cropin Technology

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Gulati noted a significant change on the fields with regard to technology’s role in improving productivity and seed quality. “Farmers (now) say, ‘Don’t help me increase production until you give me a price’. You have to ensure that farmers get a reasonable and remunerative price,” he said. “Technology alone will not succeed. It is pricing, which has to do with access to market.”

And then, he framed a killer question. “We have to develop our IPR (intellectual property rights) system or buy out,” Gulati said, citing ChemChina’s jaw-dropping price of acquiring Syngenta for $43 billion around two years ago. “Can India buy out Bayer if we want food security for the next 25 years? Bayer just bought out Monsanto for $63 billion! Or, (let’s) scale up our investments in IPR. We’re spending a billion dollars a year. We need $3 billion or $5 billion to invest. Then, India can create those miracles, which international companies and countries are getting in,” he explained.

Gulati was not exaggerating the impact of large-scale agri investments. In the US, analysts have been tracking ‘ag tech’ since late 2013, when Monsanto acquired Climate Corporation, a data analytics firm whose valuation was estimated to have touched $1 billion. The venture had raised $109 million before the exit. In the US, 2017 was a record year for farm-focussed startups, stated Mike Wholey, analyst at technology trends advisory CB Insights in a report titled ‘Agtech and the Connected Farm’.

The consolidation of the world’s biggest agri-business companies into even bigger tie-ups raised the ag-tech stakes, Wholey noted in November 2018. “Monsanto and other agricultural suppliers have heavily invested in platforms that aggregate and analyse farmer data, adding over-concentration in the industry. This could erode customers’ trust, which is crucial for acquiring farmer data,” he explained.

Competition is imperative for any online marketplace or platform. In India, agri-tech companies aren’t anywhere close to their American counterparts in terms of size or wielding that sort of influence. The action has just begun.

“ If we have to solve problems in agriculture, we don’t have to improve production. Start on the demand side of the problem. Take a more patient approach of working back from demand.”

Ashish Jhina, co-founder & COO, Jumbotail

So as a NinjaCart expands in fruits and vegetables in three states, ventures like FreshBoxx in Hubballi, Karnataka, does the same by linking agri produce from surrounding farms to a customer base of hotels, restaurants and caterers in small cities. There is MeraKisan, which supplies organic foods in four cities, backed by the Mahindra Group. Or take Jumbotail, which enables supply of provisions, staples and FMCG products to 15,000 kirana shops in Bengaluru.

“If we have to solve problems in agriculture, we don’t have to improve production,” says Ashish Jhina, co-founder and COO of Jumbotail. “Start on the demand side of the problem. Take a more patient approach of working back from demand.” Jumbotail helps rice and flour mills as well as FMCG companies find customers in small shops that use its app. Crucially, Jhina says it has applied data to help small shops or even crop mills connect with third-party credit providers to get formal credit underwritten by non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). This is based on their transaction history on Jumbotail.

Innovations of Reach

Most of the evolved agri-tech ventures from the 2014 vintage like AgroStar and EM3 AgriServices have innovated to improve farmers’ access to inputs and agriculture services.

Rohtash Mal was president of the Tractor and Mechanization Association in India between 2010 and 2012. One of his early meetings after launching EM3 with son Adwitiya in 2014 was to bring John Deere’s agricultural equipment on its platform. The pursuit took him to Delhi, Pune and even its headquarters in the US, where he pointed out John Deere’s single-digit market share in India. There was greater merit, he argued, for companies like John Deere to provide their equipment as a shared service, rather than as expensive products. Mal termed it as ‘uberisation’ of farm services for India. By 2016, even leading tractor and farm equipment manufacturer Mahindra & Mahindra launched Trringo as a shared services platform.

EM3 began on the supply side: To build an array of tractors, harvesters, etc. Then, get farmers to book the equipment, by phone or walk-ins, as a service. Finally, monitor the work on the fields. The equipment would be stocked at EM3 centres or franchises in each state. It is present in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. The Delhi-headquartered venture’s fleet has 240 tractors and 125 harvesters among other equipment.

“We don’t want farmers to have capex—only operating costs. Currently, only 25 percent of our tractor and harvesting fleet belongs to other parties,” says Mal, CEO of EM3, adding that it finished calendar year 2018 with a revenue of nearly ₹10 crore.

Its mechanised service to harvest wheat is priced at ₹1,100 per acre, which is faster and timely. It also works out to around ₹900 less than the price if manual labour were to be used, says Mal. Planting rice is priced around ₹3,500 per acre. And farmers are introduced to techniques like laser-levelling for better water retention and crop nutrition absorption. EM3 estimates its services have reached more than 30,000 farmers in 3.5 years.

“It takes six months or a year to establish ourselves in a (farming) community. After that, business is automatic,” says Mal. Most of the demand has been through farmer walk-ins at EM3’s local centres or phone calls. Payment is often in cash. The company has prioritised improving access to mechanisation over interacting with farmers on an app. “In the oncoming wheat season, we will carry out large-scale trials of ‘onlining’ them,” he adds.

At Pune-based AgroStar too, the action picked up in 2016 but—like EM3—from its call centres. Its ambition is to be to agrarian buyers what Flipkart grew to be for online shoppers: Deliver inputs at farmers’ doorstep.

For this, AgroStar centralised its procurement of agri inputs like fertilisers, pesticides, nutrients, seeds, and sprayers. Based on orders, these inputs are brought to a fulfilment centre (FC) in each state where it operates. The items are packaged and shipped from the FC to its local distribution centres, which are typically franchise retailers.

Simultaneously, in each district location, AgroStar sources last-mile delivery folk using an app called AgroEx, which gives real-time updates of delivery tasks. AgroEx users in a locality then choose delivery tasks, pick up the items from the allotted distribution centre, and drop them off at the respective farmers’ location. AgroStar is on track to clock annual sales of ₹120 crore in the current fiscal.

Its multilingual app has touched 7 lakh downloads. It has 3 lakh monthly active users. These tend to be farmers who post photos, and ask questions, seeking answers. But even today, farmers give AgroStar a missed call, says Shardul Sheth, CEO of the venture. “We have got more than 4 million missed calls on the platform. We have a call centre with more than 150 people, many of whom are farm experts. The call centre operations are in Pune and Ahmedabad, which cover demand in Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujarat,” he explains.

The app activity is crucial for AgroStar to understand farmer needs. “That’s helping us get data because they are posting specific questions on the platform,” Sheth says, citing aspects like what crop a farmer is growing, and what products he is browsing, which enable data aggregation at a pin code level. In May 2018, AgroStar partnered with IBM to triangulate such information, and predict orders a fortnight ahead. This has benefits. “Can we be prepared for a pest attack by taluk level? This helps AgroStar recommend products appropriately. It will be more of a proactive approach of solving a problem. That is the next wave of what we are doing,” Sheth explains.

AgroStar’s CRM (customer relationship management) tool runs on the mobile number, which is the unique identifier of a farmer. To personalise its recommendations, it has granular data, such as whether a farmer has drip irrigation or not, how many mobile phones the farmer has, language of communication, how many acres of land does he or she have, how many crops the farmer grows, and so on. “The data will become collateral for farmers to take credit,” says Sheth, referring to Vishwas, an app AgroStar will soon introduce.

But to understand the true potential of data in our agri-tech’s sector, you only have to look back to CropIn Technology’s Krishna Kumar, the entrepreneur who took to the seas in 2010. He has stayed the course. Almost 50 percent of CropIn’s revenues come from nine overseas markets in Africa, Europe and Latin America. It has taken its agri-tech product global.

Power of Product

Kumar put users first—the tech-savvy agronomists in input and farm food companies that had already built relationships with farmers. CropIn built a software product for farming companies that have the capacity to pay and are present across geographies.

CropIn’s first product in 2012 was SmartFarm to monitor and predict farm production. “Farms in India are small and fragmented, and farmers’ capacity to apply technologies on farm is limited,” notes Kumar, founder and CEO of CropIn. Since 2014, instead of putting sensors on farms, CropIn began to apply weather data and satellite imagery to monitor them. Parameters like temperature and rainfall on a daily basis help the product assess impact on crop harvests. “We buy data from IBM’s The Weather Company,” he says. “This provides us with parameters to predict problems before a harvest.”

The company has now built mWarehouse, a post-harvest solution for farm-to-fork traceability. This is for farming companies that want to build a facility to manage the output and process, with barcoding and other features. “The end-consumer can have transparency and traceability back to the farm. This has applications in the US and European countries,” Kumar says. Its third product is SmartSales for agri-input companies to manage their sales team and dealers. And finally, SmartRisk to help insurance companies underwrite cropping patterns. Customers for this will include NBFCs, banks and insurance agencies.

Kumar says being global requires CropIn to be cognisant of data privacy regulations like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in May last year. “While the legislation specifically caters to collection of personal data, our customers have agreements with farmers to share their farm data on cropping patterns, etc, with us,” he explains, referring to consent.

Protecting Agri Data

This is an evolving area worldwide for agri-tech. It hasn’t incurred the wrath of privacy activists quite like Google, Amazon and Facebook have in the realm of personal privacy. “Data generated by tractors, farm equipment, cows or pigs is not covered by GDPR—only data related to people,” said Todd J Janzen, an agriculture lawyer at a conference in August last year. GDPR authorises organisations to create “codes of conduct” for specific data uses.

But his paper noted a code of conduct on ‘agricultural data sharing by contractual agreement’, created by a number of European Union farm organisations. “This defines “ag data” as inclusive of a number of data streams, including farm operation data, agronomic data, compliance data, livestock data, machine data, service data, agri-supply data, and agri-service provider data,” Janzen said.

There is another precedent to this. The American Farm Bureau Federation, an independent organisation for agricultural producers in the US, formed Ag Data Transparency (ADT) Evaluator to audit companies’ agri data contracts. This also requires ventures to answer questions on ADT’s core principles. For example, portability—can farmers move ag data from one platform and use it in another? After a farmer uploads data to an ag-tech provider, is it possible to retrieve his original complete dataset in an original or equivalent format? The ADT norms require farmers to be notified that their data is being collected, and about how the farm data will be disclosed and used.

The ADT was a market reaction in 2014 to Monsanto’s acquisition of the Climate Corporation. Software is eating the farms. FBN (Farmers Business Network), another American venture, has raised $180 million from Kleiner Perkins with Google Ventures participating in its fourth round. FBN connects 5,000 farms that cover 16 million acres in the US. “Farmers can anonymously share data about everything from seed performance and chemical pricing to make informed decisions,” writes Wholey, the CB Insights analyst.

In India, agri-tech has grown outside the realm of policy because farmers see value in these software platforms. But more so in a developing country, where agriculture is a politically-sensitive sector that interests politicians and activists, agri-tech firms need to take the lead to create an industry code of conduct with regards to agri data use and sharing.

For, let’s face it: In the venture funding ecosystem, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X