Extremists find a financial lifeline on Twitch

Twitch, a livestreaming video site owned by Amazon, has become a new mainstream base of operations for many far-right influencers. Streamers turned to the site after Facebook, YouTube, and other social media platforms clamped down on misinformation and hate speech before the 2020 election.

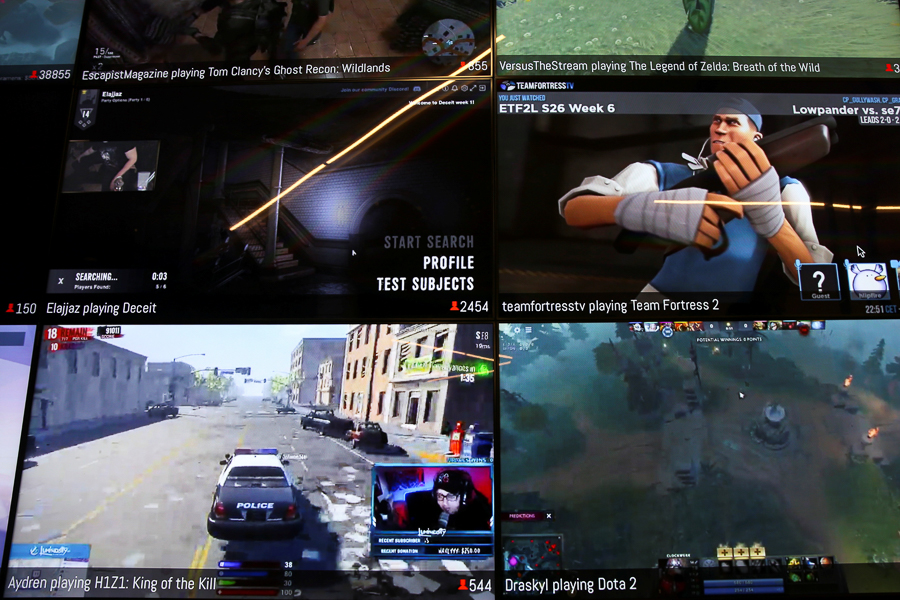

A file photo showing a wall of real-time video game play in the lobby of Twitch Interactive Inc, a social video platform and gaming community owned by Amazon, in San Francisco, California, US. Elijah Nouvelage / Reuters

Terpsichore Maras-Lindeman, a podcaster who fought to overturn the 2020 presidential election, recently railed against mask mandates to her 4,000 fans in a live broadcast and encouraged them to enter stores maskless. On another day, she grew emotional while thanking them for sending her $84,000.

Millie Weaver, a former correspondent for conspiracy theory website Infowars, speculated on her channel that coronavirus vaccines could be used to surveil people. Later, she plugged her merchandise store, where she sells $30 “Drain the Swamp” T-shirts and hats promoting conspiracies.

And a podcaster who goes by Zak Paine or Redpill78, who pushes the baseless QAnon conspiracy theory, urged his viewers to donate to the congressional campaign of an Ohio man who has said he attended the “Stop the Steal” rally in Washington on Jan. 6.

All three spread their messages on Twitch, a livestreaming video site owned by Amazon that has become a new mainstream base of operations for many far-right influencers. Streamers like them turned to the site after Facebook, YouTube and other social media platforms clamped down on misinformation and hate speech before the 2020 election.

©2019 New York Times News Service