In India, Facebook grapples with an amplified version of its problems

Facebook's problems on the subcontinent present an amplified version of the issues it has faced throughout the world, made worse by a lack of resources and a lack of expertise in India's 22 officially recognised languages

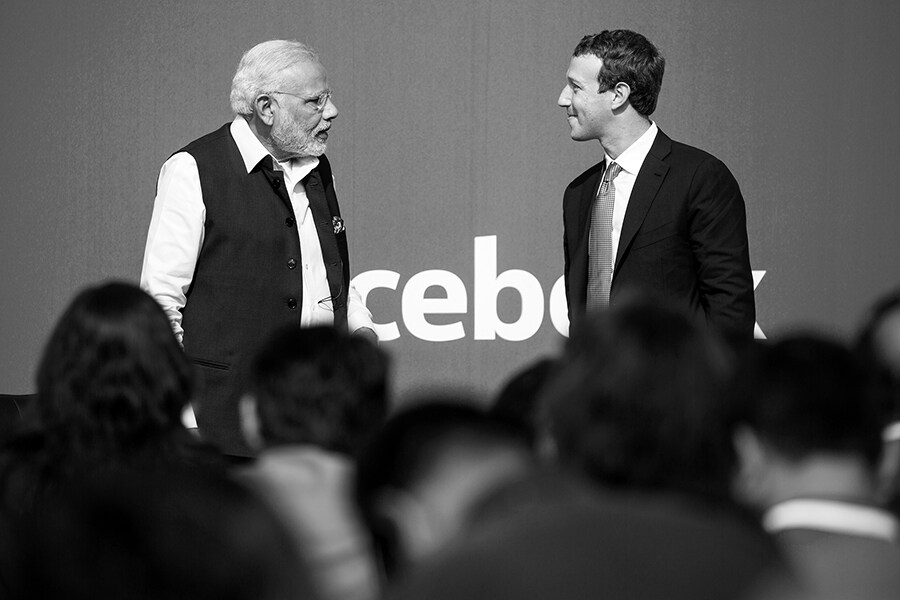

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi takes questions at a town hall event moderated by Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Facebook, at the company’s headquarters in Menlo Park, Calif., Sept. 27, 2015. Internal documents show a struggle with misinformation, hate speech and celebrations of violence in the country, the company’s biggest market. (Max Whittaker/The New York Times)

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi takes questions at a town hall event moderated by Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Facebook, at the company’s headquarters in Menlo Park, Calif., Sept. 27, 2015. Internal documents show a struggle with misinformation, hate speech and celebrations of violence in the country, the company’s biggest market. (Max Whittaker/The New York Times)

On Feb. 4, 2019, a Facebook researcher created a new user account to see what it was like to experience the social media site as a person living in Kerala, India.

For the next three weeks, the account operated by a simple rule: Follow all the recommendations generated by Facebook’s algorithms to join groups, watch videos and explore new pages on the site.

The result was an inundation of hate speech, misinformation and celebrations of violence, which were documented in an internal Facebook report published later that month.

“Following this test user’s News Feed, I’ve seen more images of dead people in the past three weeks than I’ve seen in my entire life total,” the Facebook researcher wrote.

The report was one of dozens of studies and memos written by Facebook employees grappling with the effects of the platform on India. They provide stark evidence of one of the most serious criticisms levied by human rights activists and politicians against the world-spanning company: It moves into a country without fully understanding its potential effects on local culture and politics, and fails to deploy the resources to act on issues once they occur.

©2019 New York Times News Service