The 1964 games proclaimed a new Japan. There's less to cheer this time

For both Japan and the Olympic movement, the delayed 2020 Games may represent less a moment of hope for the future than the distinct possibility of decline

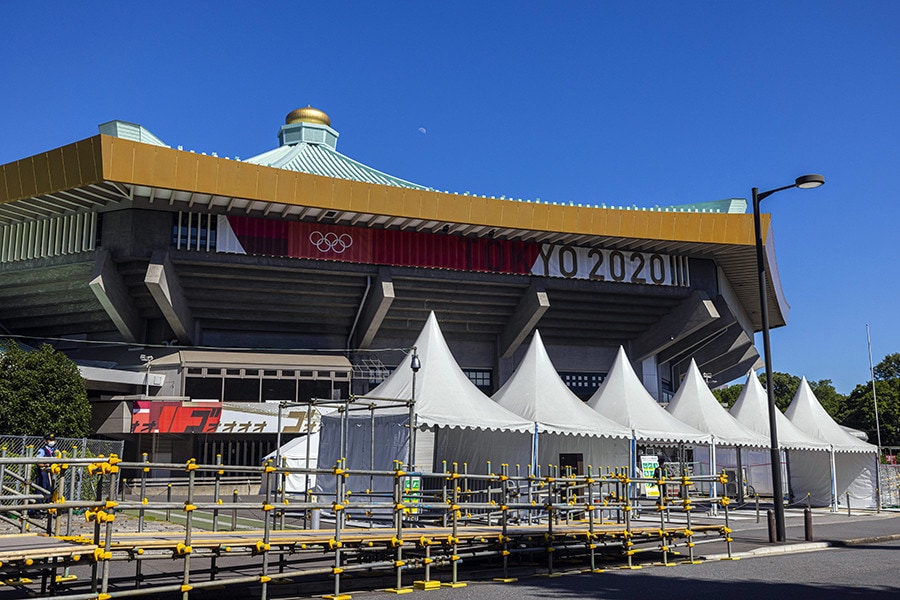

The exterior of Nippon Budokan in Tokyo’s Chiyoda ward on July 18, 2021. The country has changed vastly from that hopeful moment when the 1964 Summer Games proclaimed a new Japan, and the Olympics this time around have come to represent something different and not entirely positive; Image: Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

The exterior of Nippon Budokan in Tokyo’s Chiyoda ward on July 18, 2021. The country has changed vastly from that hopeful moment when the 1964 Summer Games proclaimed a new Japan, and the Olympics this time around have come to represent something different and not entirely positive; Image: Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

TOKYO — Under crisp blue skies in October 1964, Emperor Hirohito of Japan stood before a reborn nation to declare the opening of the Tokyo Olympic Games. A voice that the Japanese public had first heard announcing the country’s surrender in World War II now echoed across a packed stadium alive with anticipation.

On Friday, Tokyo will inaugurate another Summer Olympics, after a year’s delay because of the coronavirus pandemic. Hirohito’s grandson, Emperor Naruhito, will be in the stands for the opening ceremony, which will otherwise be closed to spectators as an anxious nation grapples with yet another wave of infections.

For both Japan and the Olympic movement, the delayed 2020 Games may represent less a moment of hope for the future than the distinct possibility of decline. And to the generation of Japanese who look back fondly on the 1964 Games, the prospect of a diminished, largely unwelcome Olympics is a grave disappointment.

“Everyone in Japan was burning with excitement about the Games,” said Kazuo Inoue, 69, who vividly recalls being glued to the new color television in his family’s home in Tokyo in 1964. “That is missing, so that is a little sad.”

Yet the ennui is not just a matter of pandemic chaos and the numerous scandals in the prelude to the Games. The nation today and what the Olympics represent for it are vastly different from what they were 57 years ago.

©2019 New York Times News Service