- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- India has been promising a lot of Covid-19 vaccines. Where on Earth are they?

India has been promising a lot of Covid-19 vaccines. Where on Earth are they?

Achieving an ambitious vaccination target requires ramping up manufacturing, enabling universal access to vaccines across geographies, tenacious micro-planning, and transparency in vaccine use and supply data, all of which is still a work in progress in India

Rafiq Khan, a villager, receives a dose of Covishield vaccine during a door-to-door vaccination and testing drive at Uttar Batora Island in Howrah district in West Bengal, India, June 21, 2021.

Rafiq Khan, a villager, receives a dose of Covishield vaccine during a door-to-door vaccination and testing drive at Uttar Batora Island in Howrah district in West Bengal, India, June 21, 2021.

Image: Rupak De Chowdhuri / Reuters

It’s been half a year since India rolled out the world’s largest vaccination programme.

Needless to say, so far, it hasn’t been entirely without hiccups. Much of that, of course, is because the Indian government is attempting a Herculean task, one where it wants to inoculate nearly 94 crore above the age of 18 in the span of a year. That number is a tad bit more than the combined population of the European Union and the US.

Since India’s vaccine rollout began on January 16, 41.8 crore people have been given the jab, with 8.6 crore people being fully vaccinated with both doses. That’s about 9 percent of the target population of 94 crore people. About 33 crore people have received their first dose, accounting for 42 percent of the target population. In comparison, in Canada, Spain, UAE, and the UK, among others, over 50 percent of the population has received both their doses. Across countries such as the US, Germany and France, the fully vaccinated population accounts for over 40 percent of the population.

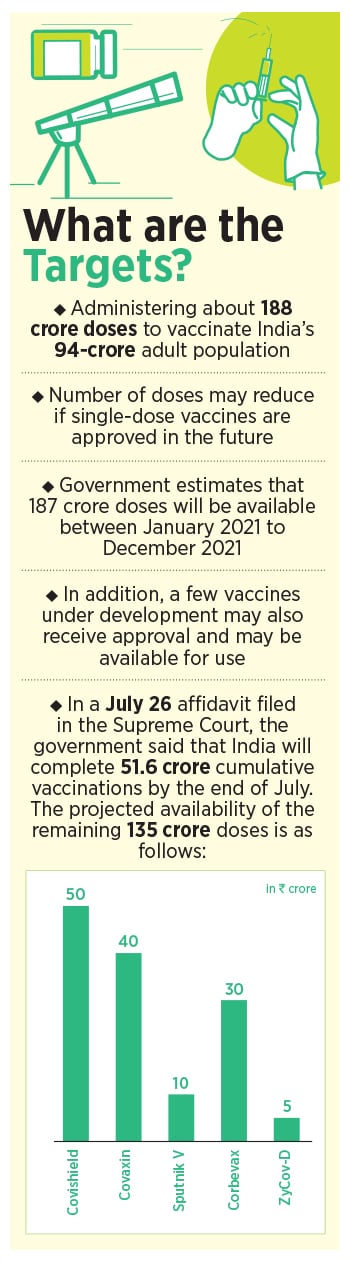

In all, the Indian government intends to use about 188 crore doses of vaccine between January and December this year, to inoculate the population, even as the pace of vaccination has remained haphazard. On July 22, the country vaccinated over 52 lakh people. Just a day before, that number stood at less than half at 22.7 lakh. And, the day before that, the number stood at 35 crore. Much of the inconsistency continues to be blamed on the shortage of vaccines reported across the country.

On July 22, for instance, the Delhi government announced that the Covishield vaccine, which accounts for 88 percent of all the vaccinations in India, will be reserved only for the second dose of the vaccine, until July 31. In Maharashtra, vaccination was stopped in Mumbai on July 22 due to a lack of vaccines.

“By mid-July or August, we will have enough doses to vaccinate 1 crore people per day. We are confident of vaccinating the whole population by December,” Balram Bhargava, India’s secretary for the Department of Health Research and the director-general of the Indian Council of Medical Research had said on June 1.

Yet, halfway into July 2021, the numbers seem to be missing their targets. India’s daily Covid-19 vaccination count reached an all-time high of over 80 lakh doses on June 21, the day the country kicked off its new vaccination policy where the Centre provided vaccination free of cost to all states. The rate of daily vaccinations, however, has been declining since.

The government plans to vaccinate 13.5 crore people in July, as compared to 11.46 crore vaccinations that it had administered in June. To administer 13.5 crore doses in July, the vaccination rate should rise to over 44 lakh doses per day, but so far, since the beginning of the month, the country has managed to inoculate 8.46 crore people, averaging about 38 lakh doses a day, a shortfall of 6 lakh doses a day.

“The high point [of vaccination] on June 21 showed that if vaccine doses were available, India has the capacity to administer upwards of 8 million [80 lakh] doses. So it is clear enough that enough supplies are not coming through,” says Shahid Jameel, director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University. Jameel was also the former chair of the scientific advisory group of the forum known as INSACOG, a multi-laboratory, multi-agency, pan-India network to monitor genomic variations in the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

So, What Do Vaccine Manufacturers Say?

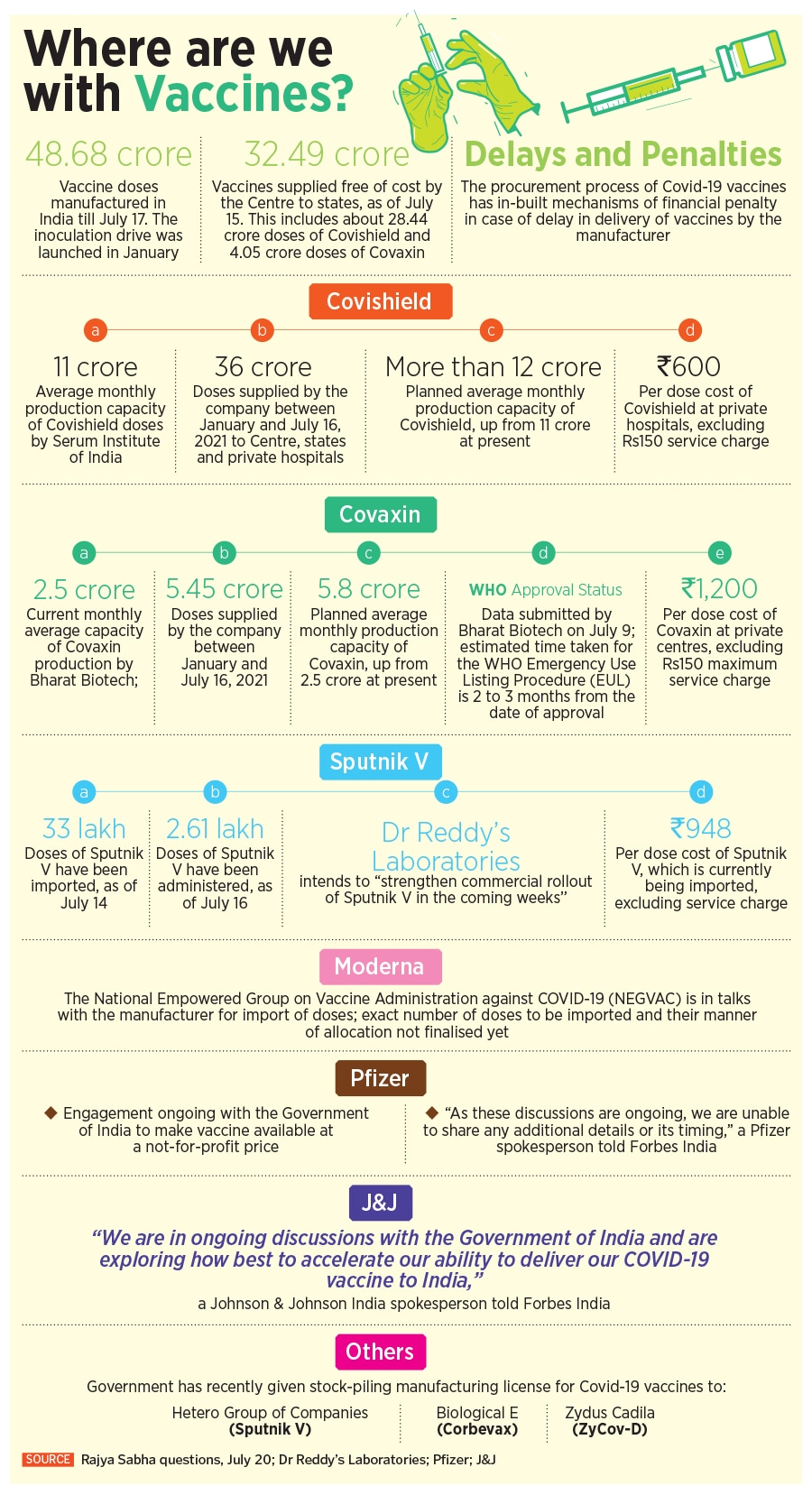

India’s Covid-19 vaccination programme has relied on just two vaccines so far, Covishield, the AstraZeneca vaccine, and Covaxin, manufactured by Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech.

Covishield currently accounts for 88 percent of the doses given in India today, while Covaxin accounts for 12 percent of the vaccines. India, of course, had expected more vaccine makers to join the vaccination plan, and take some of the load off the two vaccine makers. “Seven companies are producing different vaccines and another three vaccines are in the advanced stage of clinical trials,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said in June. “Procurement of vaccines from other countries has also picked up pace.”

Yet, the reality continues to be different. According to the Serum Institute of India, the company is currently manufacturing 11-12 crore doses of Covishield a month. While India continues to be a beneficiary of that, the company also has commitments to deliver the vaccine for global markets, particularly to Gavi, the global vaccine alliance. The company is now planning to launch Covavax, a vaccine manufactured by Novavax with an efficacy of over 90 percent in September, while it is also readying test batch production of Sputnik V by September this year.

Sputnik V, which has an efficacy of 91.6 percent, is expected to see over 100 crore doses being manufactured in India, after the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), the Russian government’s sovereign wealth fund, tied up with some seven manufacturers to manufacture the vaccine in India. While the vaccine had received necessary approvals in April, it is yet to be used significantly in India’s inoculation drive.

Dr Reddy’s Laboratories (DRL), which has an exclusive agreement to import and sell the first 25 crore doses in India, had received about 30 lakh doses by June 1 and about 360,000 shots by early this month. Of those doses, as per a response to a question in the Rajya Sabha, Union Minister of State for Health Dr Bharati Pravin Pawar, said that only close to 2.61 lakh doses had been administered as of July 16.

Speculation was rife that the Sputnik V vaccine’s rollout was being delayed particularly since the first and second doses of the vaccines were not being made available in equal doses from the manufacturer. “We would like to reiterate our commitment that all hospitals that received dose 1 from us will also receive dose 2 in equal quantity on time,” a spokesperson for DRL told Forbes India. “Neither the ongoing soft commercial launch nor work towards its ramp-up in India have been put on hold.”

“The Sputnik V team and its partners in India are working to ramp up production,” a spokesperson for RDIF told Forbes India. “Sputnik V open strategy of technology transfer to 25 top producers in 14 countries brings production to over 800 million [80 crore] doses a year. In India, the RDIF has production agreements with experienced vaccine manufacturers, including Serum Institute, Gland Pharma, Hetero Group of Companies, Panacea Biotec, Stelis Biopharma, Virchow Biotech, and Morepen. We are expecting production in India to come fully onstream over the course of the next few months.”

Bharat Biotech and Zydus Cadila did not respond to queries sent by Forbes India.

The National Empowered Group on Vaccine Administration against Covid-19 (NEGVAC) has been in talks with the offshore manufacturers of the Moderna, Pfizer, and J&J vaccines for import of doses, but the government says the exact number of doses and the manner of their allocation has not been finalised yet.

“Pfizer has underscored its commitment to the people of India through ongoing engagement with the Government of India to make the vaccine available for use in the country and at a not-for-profit price,” a spokesperson told Forbes India. “Our frameworks in India are consistent with those anywhere in the world where our vaccine is being supplied. As these discussions are ongoing, we are unable to share any additional details or its timing.”

In June, the Indian government allowed domestic pharmaceutical company Cipla to import the Moderna vaccines in India. However, the US biotech major demanded legal indemnity in the country before making its vaccine available. Manufacturers are seeking indemnity, which covers them in case of a serious adverse event and makes the government liable to pay the damages from a special fund. In April this year, the government had allowed foreign vaccine makers to bring their vaccines to India without having to conduct the mandatory phase two and three clinical trials.

“At Johnson & Johnson, we remain fully focused on bringing a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine to people in India,” a spokesperson for Johnson & Johnson, which is also seeking legal indemnity in India, told Forbes India. “We are in ongoing discussions with the Government of India and are exploring how best to accelerate our ability to deliver our Covid-19 vaccine to India.”

Big task ahead

To meet the inoculation targets of administering 188 crore doses by year-end, the government, on May 13, had shared a roadmap on vaccine manufacturing in India from August to December. While banking heavily on 75 crore doses of Covishield and 55 crore doses of Covaxin, together comprising nearly 70 percent of all vaccines, they had also included an estimate of doses from other vaccines: 30 crore doses of the Corbevax vaccine by Biological E [which has also been contract manufacturing the J&J vaccine], 15 crore doses of Sputnik V vaccine, 20 crore from Novavax [ to be manufactured by the Serum Institute of India], 5 crore from Zydus Cadila and 10 crore doses from Bharat Biotech’s nasal vaccine.

However, in an affidavit filed with the Supreme Court on June 26, the Centre has estimated that as per current supply, India will complete 51.6 crore cumulative vaccinations by the end of July. The projected availability for the remaining 135 crore doses included 50 crore doses of Covishield, 40 crore doses of Covaxin, 30 crore doses of Corbevax by Biological E that is still under Phase-3 trials, 5 crore doses of Zydus Cadila’s DNA vaccine ZyCov-D and 10 crore doses of Sputnik V.

In a July 2 press conference, VK Paul, Niti Aayog member (health), said that the government’s roadmap of 216 crore doses is an “optimistic” one, which was made by banking on the “reputation” of the vaccine manufacturers, and should be seen in a dynamic context. He added that the government shared those projections because there were questions being raised on the availability of vaccines. According to him, even if the government continues to depend on just the two main suppliers—Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute of India—the “situation is satisfactory”.

In a response to a question in the Rajya Sabha on July 20, Dr Pawar reiterated the government’s projections, estimating that around 1.87 billion [187 crore] doses will be available between January 2021 to December 2021. “In addition, a few vaccines under development may also receive approval and may be available for use to vaccinate the eligible population,” she said. No detailed break-up of vaccines and their availability was provided.

The Union Health Ministry has also countered the claims of states flagging supply constraints, saying that adequate supplies were being sent to states and that they are informed “well in advance” about the time and volume of doses they are scheduled to get. “From a distance, it appears that both are trying to score brownie points to manage public perception,” says Jameel. “The sensible thing to do would be to make public all the data on use and supplies. While the former is, the latter is not.”

What Will It Take To Achieve Targets?

According to the Union Health Ministry, India had 405,513 active cases on July 23.

The number of cases should not be a reason for panic, and what one needs to keep an eye out for is hospitalisation and deaths, says Dr Giridhara R Babu, head, life course epidemiology at the Public Health Foundation of India. “If hospitals are not overloaded, and deaths are not high, then cases coming just show that your surveillance system is good,” he says, adding that hospitalisation will depend on how many people are vaccinated between now and whenever the next Covid-19 wave hits.

Even if India has not reached the desired level of vaccine coverage, Dr Babu explains, the impact of the third Covid-19 wave is unlikely to be as bad as the second wave because a reasonable number of people have already been exposed to the coronavirus. A nationwide serosurvey conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) across 70 districts in 21 states in June and July shows that while two-thirds of Indians above the age of six have Covid-19 antibodies, about 40 crore people, or one-third of the population, are still vulnerable. This is the first time that children aged 6-17 years were included in the serosurvey.

While the overall seroprevalence of Covid-19 antibodies stands at 67.6 percent in June and July, which is higher than 0.7 percent in May-June 2020, 7.1 percent in August-September 2020, and 24.1 percent in December 2020-January 2021, there is “no room for complacency”, says Dr Bhargava of ICMR. He has also stressed that it is essential to maintain Covid-19 appropriate behaviour and curb community engagements and all kinds of congregations.

Jameel points out that the R0 [R-naught] for Covid-19 in India has increased over the past few weeks, but is still below the value of 1.0. According to the Harvard Global Health Institute, the R-naught represents, on average, the number of people that a single infected person can be expected to transmit the disease to, or the average “spreadability” of an infectious disease.

Jameel points out that the R0 [R-naught] for Covid-19 in India has increased over the past few weeks, but is still below the value of 1.0. According to the Harvard Global Health Institute, the R-naught represents, on average, the number of people that a single infected person can be expected to transmit the disease to, or the average “spreadability” of an infectious disease.

“If it climbs above that [1.0], we will have a growing outbreak,” he says. According to Jameel, while new Covid-19 cases are important, more important is a focus on moderate and severe cases that require hospitalisation. “We are unlikely to see the kind of surge we saw in March to May, because of many more exposed (and thus protected) people, and the fact that we have already been exposed to the highly infectious Delta variant,” he explains. “Still, it would be prudent to have sufficient hospital capacity, oxygen, and medicines on standby.”

Dilip Jose, MD, and CEO, Manipal Health Enterprises, agrees that an adequate stock of medicines and medical oxygen at the district level should be a key priority based on learnings from the past, apart from a seamless process of testing and tracing to manage local spikes. “The third step needs to be an appropriate triaging mechanism that restricts hospitalisation to only those who genuinely require it,” he says, adding that infrastructure ramp-up to ensure oxygen beds and ICUs must happen now when India is between waves. “Finally, it should also be ensured that the inoculation drive does not suffer, as the only way out of this pandemic is to reach our vaccination goals as soon as possible.”

Just meeting the vaccination numbers, however, is not sufficient, says Dr Babu. He points out that right now, the areas with high vaccination coverage are largely in and around metros where people are aware. The first priority, therefore, must be to make vaccines universally accessible across rural and remote areas, he says.

“Second is micro-planning, which the Centre must insist that states undertake. How many people are there, how many vaccines are needed for that area, where the vaccination centres have to be, those details have to be strengthened now,” he says. The third crucial part, according to him, is to mobilise people, which means ensuring that people come in to get their vaccines, and even if they do miss inoculation due to unavailability of vaccines or other reasons, there must be strategies to get them to the vaccination sites again when doses are available. “This is the only way forward, and has to be expressed clearly even in review mechanisms.”

Jose agrees that a uniform and rapid coverage across all geographies is what would shield the country from repeated waves of cases as well as the possibility of more mutants. “With more vaccines in the pipeline, availability concerns would soon be over. In the meanwhile, the focus needs to be on overcoming hesitancy, besides ramping up on logistics of delivering the dose on the arm in rural areas,” he says. “It is the collective responsibility of the entire health care sector—both public and private—to get us there,” he says.

According to Jameel, states should plan based on vaccine delivery capacity and convey to the Centre ahead of time, while the Centre should make doses available based on that capacity. “Both should make all the use and supply data completely transparent. The same goes for pandemic management,” he says. “Transparency builds trust in the system and compels people to follow rules. That element appears to be missing.”