Leading through emotion

Art as a toolbox for leadership insights

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

In a recent, highly experiential and interactive Discovery Event, Professor Ina Toegel highlighted the importance of minding, understanding, managing and expressing emotions to boost team creativity and innovation. She illustrated these concepts using examples from films, music, visual arts, literature and performance art.

Too often, organizational leadership focuses on ever-increasing results in a fast-paced and changeable environment with little space given to emotion. So, you may ask, what can organizational leaders possibly learn from the arts? Quite a lot, as it happens.

Artists-as-leaders and leaders-as-artists

Successful artists, like leaders, generally start off with a vision and are the first to create something. They are often ahead of their time, able to visualize things that do not yet exist, passionate and dedicated to transforming their vision into reality. In many cases, that involves communicating their passion to others to motivate them to execute their vision.

Leaders, like artists, are inspired by a vision for their organization; they need to galvanize others to execute that vision.

Artists and leaders both need aesthetic intelligence and must constantly innovate and communicate their ideas. Just as artists touch people’s emotions through their work, leaders need to touch their teams’ emotions to bring them on board and get them to follow, using meaning and significance as drivers.

Emotions allow people to connect with one another, and by recognizing and acknowledging their subordinates’ emotions, leaders can create the psychological safety that allows their teams to innovate and perform at their best. But what place are emotions truly given in the workplace?

Setting the stage: Connecting through artistic expression

Professor Toegel asked participants to work in teams to produce a drawing. They were allowed to discuss the task among themselves. She then asked the teams to draw another picture and give it a title, this time in silence. For the first drawing, everyone focused on the task, as is often the case in the workplace.

For the second drawing, everyone concentrated on what the others were doing, building on their ideas. Participants described the process of the second task as more meaningful and more fun – with collective laughter outbursts as various team members added surprising twists to the drawings. They also described the output as more creative and innovative. Paradoxically, silence can sometimes be the best way to communicate.

A compelling example of the power of communicating through silence is performance artist Marina Abramovich’s installation at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art entitled The Artist is Present, which lasted three months. Two chairs faced each other in the middle of a large open space. Abramovic sat on one and invited museum visitors to sit on the other and join her in silent communication. Video clips of the event show people expressing a huge array of emotions – anxiety, discomfort, sadness, happiness – entirely through facial expressions, body language and eye contact.

Minding emotions

Silence is used in various ways to focus attention: Silence in commercials increases attention to and retention of information; comedians use silence for effect. Silence between two people may indicate a breakdown in communication but it could also mean that they are attuned, at one with each other. Some find silence disconcerting, others relish it. Observing a minute’s silence in remembrance of people who have passed away creates a sense of a shared history, an emotional bond, and can facilitate affiliation.

Being silent is thus a way of achieving mindfulness – being in the moment and aware of one’s surroundings. Organizational leaders are required to achieve results, which they do by executing specific tasks. Their focus is thus generally on actions rather than on the emotions of others. Yet this can affect creativity, productivity and efficiency.

By being mindful of people’s emotions, for example through “silent” exercises (similar to the team drawings mentioned earlier), leaders can boost connections with and among team members, which can promote creativity, productivity and efficiency. This means observing and experiencing emotions in oneself as well as in others, which requires being in the present moment. Using silence in a team setting can create connections beyond the task. Another exercise borrowed from the world of performance art could be to ask team members to form pairs and sit face to face in silence for one minute and then share their observations and feelings. Or, more daringly, get team members to wear blindfolds and headphones and walk around the room. People will inevitably bump into each other. What do they do? How do they react?

Understanding emotion: Personality as a driver of emotion

Emotion is largely driven by who we are – our personality. The five-factor model of personality, the Big Five, offers a comprehensive, unifying framework for identifying five personality dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and openness to experience. Each of these dimensions comprises six facets. A Big Five personality test reveals preferences on five main dimensions, or personality drivers, and their respective facets. The unique combination of someone’s preferences is what defines their personality and drives their behaviors.

Extraversion describes one’s comfort level with relationships. Extroverts tend to maintain a large number of relationships. Introverts tend to be reserved and have fewer relationships.

Agreeableness refers to a person’s propensity to defer to others. High scorers value harmony over having their own way. Low scorers focus on their own needs more than on those of others. Business leaders tend to score lower in this dimension as this correlates strongly with promotion, but this characteristic makes it harder for them to form a balanced team of people with a range of preferences. Their team members are thus less likely to be open to disclosing to others due to the lack of psychological safety. Yet, as researchers at Google found, a high willingness to disclose is an important factor in boosting innovation.

Conscientiousness is about the number of goals on which a person focuses. High scorers pursue fewer goals and tend to be responsible, persistent and achievement-oriented. Low scorers tend to be more easily distracted, less focused and more hedonistic.

Emotional stability defines a person’s ability to process negative emotion. People high on this dimension tend to be resilient, while those at the other end of the scale tend to be anxious and nervous. One way to diffuse these feelings is by naming the emotion like singer-songwriter Adele does. She manages her performance anxiety by sharing how she feels with her audiences.

Openness to experience refers to one’s range of interests. High scorers are fascinated by imaginative, creative and intellectual activities. People who are low in this dimension tend to prefer the familiar. Companies are increasingly trying only to recruit explorers, but this is risky because executors are needed for implementation.

Why does all this matter? When a person’s actions are not in accord with their natural preferences, there is a preference gap, which results in a personal cost in terms of time, stress, effort or energy. Being aware of preferences allows us to predict our own emotions and those of our team members. It helps to understand what makes us and others happy or unhappy and what concerns we and they have and how these can be alleviated. It also increases our awareness of when to release the decompression valve to avoid overflow and to redress the balance. For example, if an introvert has a people-facing job that involves a lot of interacting, they need to ensure that they set aside some peaceful down-time at the end of their work day to decompress and recharge their batteries.

Leaders can use the Big Five personality tests to map out their own profile and those of their team members. Disclosing the relevant information within the team helps everyone concerned understand and predict behaviors and avoid issues. Additionally, different personality profiles bring a variety of skills and abilities to the team. The real stars of the show are not always those in the foreground.

One of the reasons that everyone remembers The Beatles drummer Ringo Starr was because the band consciously presented itself as the “Fab Four” rather than as a front man (or two) with a supporting band. Ringo was elevated on the stage so he could be seen. The band knew that Ringo’s ground-breaking creativity was key to their success, even if he was not the best drummer technically.

Recognizing, valuing and utilizing the specific characteristics and emotional profiles of each team member can increase the psychological safety that is essential to disclosure, which is key to boosting creativity and innovation.

Managing emotion

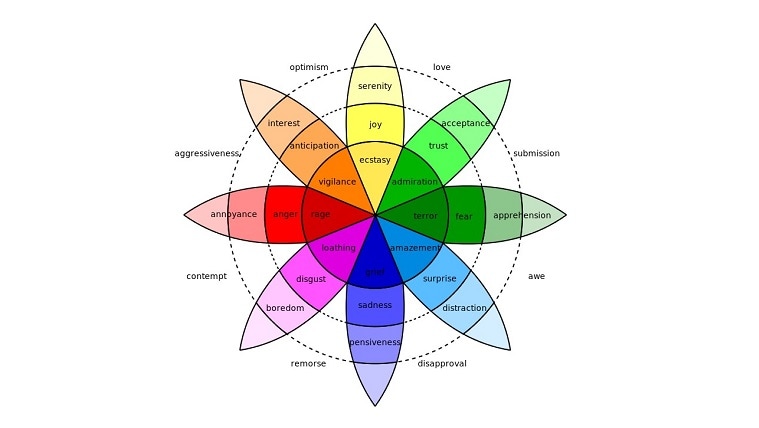

While it is important to open the door to emotions, it is equally essential to describe them accurately. There are numerous words in the English language to describe emotions; it has at least 60 different ways just to describe the emotion of “anger.” Naming emotions more precisely invites others to ask more specific questions, for example: Why are you resentful? About whom? What can you do about it? This is more actionable than focusing on what or how someone feels. Feeling bad, sad, blue or melancholic are different nuances of a similar feeling and may require a different response to dissipate the feeling; “openness” to change is not the same as “embracing” change; and saying “I am angry” is vaguer than “I am resentful about…”. Furthermore, you would not respond in the same way to someone who is irritated and someone who is infuriated. So granularity and nuances help others better understand what one feels and how to react. The emotion circle (Figure 1) shows how the eight primary emotions – anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, anticipation, trust and joy – interact and vary in intensity.

Figure 1: Wheel of Emotions

Source: Plutchik, R. “The Nature of Emotions,” American Scientist, 1980

Some emotions such as anger, anxiety and vulnerability are often considered to be negative, but when they are channeled in a positive way they can become drivers of success. It is a matter of matching up tasks and emotions. For example, it is better to analyze situations and discuss problems when energy and feelings are less intense, but intense energy such as anger can be useful in “attack” situations such as competitions.

Strong positive energy and feelings are conducive to productive brainstorming, whereas stronger positive feelings combined with less-intense energy may be more useful for consensus building and reflection. Award-winning film director Martin Scorsese stated that he often feels angry but that he diffuses it through humor and irony.

Another important consideration is that there are cultural and gender differences in the way emotions are perceived, projected and accepted. For example, it seems to be more acceptable for men to express anger than for women to do so; and men mainly focus on being respected whereas women tend to focus on being both respected and liked, which is much tougher.

Leaders could learn to better understand their own emotions and those of others by inviting their team members to describe their emotions using specific granular language and ask questions that can lead to solutions during team check-ins.

Emotion, connecting and creativity

Is it possible always to control emotions or do they somehow “leak out”? And how does hiding our underlying emotions affect us, others, our creativity and our ability to connect to others?

The more we express emotions, the easier it is to connect and bond with others. When people are more connected they feel safer psychologically, which in turn encourages them to disclose more, and that is an essential ingredient of innovation and high-performing teams. But not only! Work should also be fun and engaging. Unfortunately, it seems that creativity has been educated out of many of us.

Creativity can take many forms, and artists of all kinds express their emotions, sometimes deliberately, sometimes unwittingly, in their work. Self-portraits can be particularly revealing, especially when we compare them to portraits painted by others. Indeed, the way we present ourselves conveys a lot about us. Why, for example, did Van Gogh focus on his missing ear in one of his self-portraits instead of showing a more idealized and whole version of himself?

Critically acclaimed comic Louis C.K. observed that success only came to him once he stopped sharing what he observed and started joking about his own emotions, which allowed him to connect much more with his audience. His popularity grew even more when he went on to share his greatest fears.

A useful exercise to reveal perceptions within the team is to invite members to disclose their first impressions of each other. People pick up a lot of information about others in a short period of time. This can be scary. But it can also be useful. It takes eight interactions to undo a first impression, so knowing how others perceive us allows us to adapt our behavior and the way we present ourselves if need be.

Key takeaways

Being mindful of and open to emotions – our own or those of others – and to what triggers them is an important aspect of leadership. However, it is equally important that these emotions be described accurately and with granularity in a way that makes them actionable.

Conducting a Big Five personality test and sharing the information within the team can help build empathy and improve predictability. Recognizing emotions and encouraging people to share them can boost creativity and increase joy in the workplace. It also enables people to connect, which in turn creates a psychologically safe space, both of which are essential to high-performing teams.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from IMD, a leading business school based in Switzerland. http://www.imd.org]