Investing Is For Grown-Ups

Especially in 2011. All but the most hard-working and fastidious investors will be punished severely in a year marked by troubling predictions

During the Christmas week, a text message hopped from mobile phone to mobile phone pretty much saying one would have made more money in 2010 by investing in onions than in equity shares, fixed deposits, real estate, or in any other asset class. And how true it was!

From its normal price of less than Rs. 10 a kilogram at the start of the year, the favourite vegetable of the Indian poor zoomed to Rs. 80 by late December before the government stepped in and brought it back to Rs. 40 levels. If you had figured out a way to preserve onions for a year, you could have made anywhere between 300 percent and 700 percent profit, depending on when you sold. Compared to this, the equity markets gave a mere 16 percent and the deposit rates rarely crossed 8 percent. Real estate prices failed to breach the 18 percent mark even in the hottest markets.

Building wealth through onions is indeed a fantasy. But the price rise wasn’t. It was rudely symbolic of the price India has begun to pay for fast growth. Rising food demand has made inflation the norm rather than the exception; the country is vulnerable to commodity supply shocks. Prices of assets are back to historical highs taking them beyond the reach of many. Interest rates have not stopped going up. The costs of doing business are rising. Political stability has come under question with a wave of scandals and a Parliamentary logjam. The vicissitudes of the global economy — especially the US and China — have begun to tell more sharply on India’s financial markets.

“The way a mix of signals is emerging, the threat of a slowdown in the economy is a very real possibility in 2011,” says Abheek Barua, chief economist of HDFC Bank. “I won’t agree with this notion that the India growth story is entirely OK.”

It is this challenging climate that the investor is walking into in the New Year. Making sense of the financial markets has become increasingly difficult in recent years due to higher complexity and volatility. It will be even more so in the New Year as a myriad of global and domestic factors send conflicting signals about what to expect.

The Wild West Factor

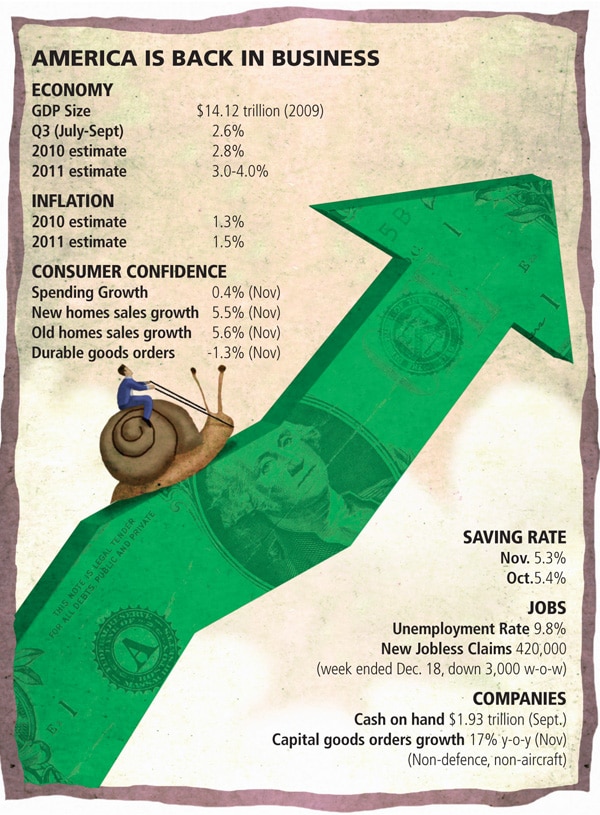

It was as if Santa Claus had taken a special interest in reviving the US economy this Christmas. The world’s largest economy had indeed posted impressive numbers in the previous couple of quarters, but a decisive signal about the return of consumer demand proved elusive.

In the weeks running up to Christmas, economists pointed out that unemployment was still a high 9.8 percent and consumers had not begun to spend. They reasoned any growth was coming from abundant liquidity and failed to touch most Americans.

But the holiday shopping season put that speculation to rest. Pre-Christmas sales in 2010 reached a brisk $584 billion, a figure even higher than the pre-crisis 2007 sales. MasterCard revealed that retail spending rose 5.5 percent in the 50 days to Christmas. Online sales grew 15 percent. And nearly half of US customers said they would shop in the week before New Year. All signs that the US economic recovery is getting more entrenched.

“I do think that in 2011 we will see shift of leadership in the global economy back to the other side of Atlantic,” says Suman K. Bery, director general of the National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER). He says two decisions of the Obama Administration — one to extend George Bush era tax breaks and the other to infuse as much as $600 billion through the second tranche of quantitative easing — are boosting consumer demand and confidence.

It is terrific news for America, for the world and to some extent, Indian companies serving US customers. But it could actually bad news for the Indian investor. Why?

If the US becomes good to invest in again, portfolio investors looking for quick returns will have less incentive to send money to emerging markets such as India.

In fact, the bounce-back in the Indian stock markets since March 2009 happened largely due to such inflows from America. The first installment of money infusion leaked out of the US because investors didn’t see much potential in a job-losing economy. Some of that money came to India.

But in 2011, the US could add $350 billion to its economy (at about 3 percent growth). That is roughly equal to a 25 percent growth in Indian economy. But while equity shares and property in India are trading at sky-high prices, US equity and real estate are extremely cheap. Salivating fund managers say the year 2011 could go down in history as the best year of the era to invest in the US.

There is evidence that American companies have already begun the next investment cycle. They are sitting on a cash hoard of $1.93 trillion in stimulus-led profits and have been building up inventory. They produced extra goods worth $112 billion in the third quarter to catch holiday sales and sold them in December. The new hope will lead to fresh production and capacity expansion in 2011.

The Sticky East Factor

The dichotomy with India is striking. The Rudyard Kipling cliché about the West and East was never truer than now. While the US economy is witnessing low inflation, plenty of cash supplies and near-zero interest rates, India and China face rising inflation forcing them to increase interest rates. In India, liquidity looks like a corset - skin-tight and increasingly squeezing.

“The growth prospects and the corporate profit prospects look a little worse in 2011 than in 2010,” says Barua. He says inflation hasn’t responded to a slew of policy measures and the Reserve Bank of India could resort to three or four rate increases during the year. China is already preparing to sacrifice some growth to contain inflation; India will have to follow.

“All told, my expectation is that the economy will still grow by 8.5-9 percent, but with a risk to the downside,” says Bery.

The onion price shock is rapidly spreading to more food produce such as tomato, chillies, cauliflower and garlic. This may just be the first phase of a commodity price run in 2011. Unseasonal rains and cold have affected post-Kharif (monsoon season) sowing and harvest data could be lower in 2011. Given that carry-over stocks are low in a number of crops, prices could skyrocket.

Globally, the abundant cash liquidity will boost the prices of commodities where there is a demand-supply mismatch. This will lead to further inflationary pressures in India.

Given that economic indicators are deteriorating, investors would have still drawn some comfort if political stability had remained unaffected. The fallout of the telecom scam as well as a slew of other corruption scandals has led to a face-off between the country’s top two parties, the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party. Investors will have to discount the political risk — including a slight threat of a mid-term poll — before committing money to assets.

“Suddenly, the corporate governance issues have raised some sort of a red flag in the markets. If it is considered a one-off thing, the markets may shrug off the impact. But if these things will continue, it will be very bad for the investment climate,” says Ajay Parmar, head of institutional research at Emkay Global.

Now for some scenario building: The biggest joker in the pack, of course, is China. The prospect of a loss in Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) numbers is more than likely now, but the question is whether it will be a hard landing or a gradual cooling down. If the GDP plunges to below 7 percent, it could seriously dent the global economy.

China is one of the largest consumers of various commodities and a drop in its demand will lead to a severe correction in their prices. While it will be a boost for India on the import side by making oil cheaper and reducing inflation risk, it will hit the export side hard. In the last few years, India has diversified its export basket to promote trade with Asean nations. China’s troubles will take down all these countries and India’s exports will suffer. “On balance, China’s slowdown will hurt India,” says Barua.

Investors could flee emerging markets if their investments in China go bad. They are already becoming more risk averse given the European debt contagion, which doesn’t show signs of abating anytime soon. India will thus have to pay the price for being a member of the BRIC club.

The Valuation Pain

The most compelling argument against investing in India at the end of 2010 has been the valuations of various assets.

The stock market doesn’t come cheap. For every rupee of last 12-month profit in companies that figure in the BSE Sensex and NSE Nifty, we pay 23 rupees to buy a share. It is marginally higher even than the levels at the peak of the dotcom bubble. And we all know what happened then.

Real estate is prohibitive. At the sight of some demand from home buyers, builders have hiked the prices compromising that demand. Without a correction, most buyers and investors are not likely to return.

Infographic: Corbis

Commodities pinch wallets. Housewives in India will be praying for economic slowdown in the US and China, if only to be able to meet their

monthly budgets.

Raw material costs and rising interest rates will push up the cost of doing business and thus erode profitability. It makes more sense to lend to companies than to own them.

A lot of money that could have been saved in banks or invested in businesses has been locked up in gold as Indians want to ride the boom in the yellow metal. They put more than Rs. 100,000 crore in gold in 2010. It will take a sustained correction to pull this money out of gold and channelise it to the productive economy.

The squeeze is already being felt by the banks. While credit growth has more than doubled to 23 percent during the year, deposit growth slowed down to 15 percent from 18.4 percent in 2009. This will soon translate into lost business growth. For the investor, all this means that the obvious money-making opportunities are vanishing.

It would take a sharp eye to spot the silver lines in the economy and the hidden openings on the road to prosperity.

Islands of excellence

The famous India Growth Story has not entirely lost its merits. There is a fighting chance that India may overtake China as the fastest growing economy, if not in 2011, at least soon after. That makes the current bad time a very good time to invest. There are signs that agriculture is resurgent.

In the quarter to September 2010, it grew by as much as 4.4 percent, compared to a token 0.2 percent in 2009-10. It surely has benefitted from a low-base effect but economists expect agriculture to do well in 2011 also. Not only the monsoon has been fulsome, but rising commodity prices have also attracted farmers to sow more. (Take onion. In the last three years or so, output has risen 60 percent to 18 million tonnes. The same is true for a growing number of crops.)

The second bright spot is the rural economy. The farmer is cash-rich. Higher minimum support prices and the various government schemes designed to take the benefit of subsidies directly to the farmer are helping rural consumption. He is not only investing in better farming and irrigation equipment, he is also buying things for his home.

The third factor is the changing energy profile of India. The country is slowly but steadily shifting to become a major user of natural gas. This will not only harm the environment less, but also open up avenues for investments in storage tanks, pipelines and delivery services.

Indian companies have lived through interest rates of 20 percent and above until just more than a decade ago. They also know how to extract business from a languishing economy. Companies with a long heritage are unlikely to be hit hard by short-term bumps. Many of them have smartly tied up raw material supplies through captive units or alliances and they will not be hit by rising raw material costs.

As wage levels increase, the average Indian’s desire for a better standard of life will unleash demand for high-value products. The mission of financial inclusion is taking root in remote corners of the country and that will bring more new consumers into the market.

In the following pages, we detail these trends and tell you how to make the best out of them. Your returns will depend on careful asset allocation. It is certainly not the time when the unprepared investor could make money by blindly following the herd. It is the time for being choosy, cutting down risk and buying cheap.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)