Structural reforms or falling oil prices, what exactly is inflation responding to?

Low oil prices may not be the only reason why inflation is down. Structural reforms by the government may be playing a larger role

The government has many plans, but most of them are only on paper as of now. They will eventually materialise as macro-economic factors in favour of the Narendra Modi-led government, says Rajiv Shastri, a trained economist and Managing Director and CEO of Peerless Funds Management. The fall in oil prices, for one, will benefit India greatly, he tells Forbes India. Excerpts:

The government has many plans, but most of them are only on paper as of now. They will eventually materialise as macro-economic factors in favour of the Narendra Modi-led government, says Rajiv Shastri, a trained economist and Managing Director and CEO of Peerless Funds Management. The fall in oil prices, for one, will benefit India greatly, he tells Forbes India. Excerpts:

Q. What are the prime concerns for you at this point?

The primary concern is the time gap between the expectations and the outcome of the measures taken by the government. While many expect such steps to translate into economic growth soon, the benefits of many long-term measures may kick in only after nine to 12 months. Initiatives which support international trade, FDI in railways, removing coal production bottlenecks, solar power policy, easing of labour laws, Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana and GST [goods and services tax],

among many others, have very far-reaching benefits. While some of these may manifest earlier, the true impact will be felt only in the second half of FY2015.

If this time gap results in economic activity remaining subdued, the subsequent shortfall in revenues combined with our expenditure commitments will lead to huge fiscal gaps. This will result in increased borrowing with a consequential impact on interest rates. It has the potential of derailing the beneficial economic cycle that the nascent low inflation scenario promises.

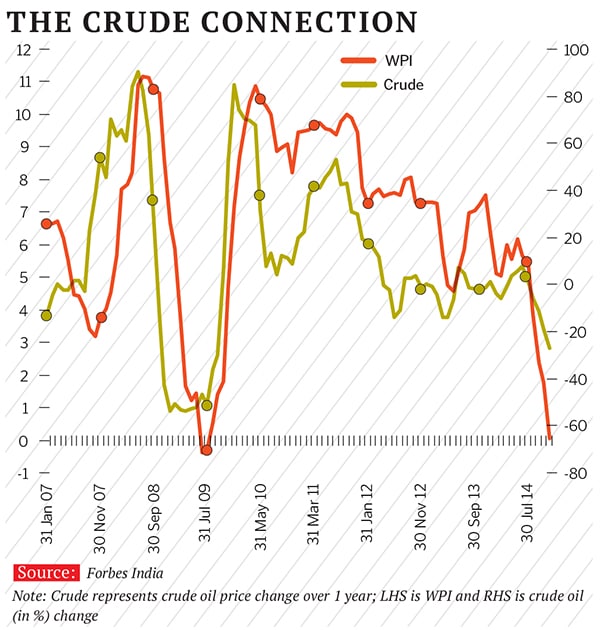

The current low inflation environment is more due to some measures instituted by the government and low non-oil commodity prices. Lower oil prices haven’t really been passed on to the economy. While some part of the fall served to reduce the government’s subsidy burden, some of it has been used to support government revenues through increased excise and other duties on petroleum products. Due to this, it’s extremely difficult to establish a logical link between low oil prices, low inflation and potentially lower rates.

Q. Are you saying oil prices and interest rates are not related in India?

There is some linkage, but the correlation is lower because of the manner in which successive governments have intervened in the domestic oil market. When oil prices were rising, government intervention did not allow this to feed into domestic rates and as a result, inflation didn’t directly respond to oil prices. In recent months, oil prices have halved while the cost of petroleum products in India hasn’t. To my mind, inflation has responded more to structural measures undertaken by the government to contain the prices of agricultural products, lower non-oil commodity prices and subdued economic activity. This has coincided with lower oil prices primarily because the prices of other commodities have also fallen at the same time.

This leads to a piquant situation. On one hand, if oil prices were to remain low and government revenue needs decrease over a period of time, we may see domestic prices falling meaningfully. However, if oil prices were to rise again, which is possible given that we are at multi-year lows, domestic prices may increase in lockstep, undoing much of the benefits of the measures mentioned earlier. I believe the Reserve Bank of India [RBI] would be concerned about this while deciding on interest rates going forward.

Image: Christian Hartmann / Reuters

A Total oil refinery in Grandpuits, France. Falling global prices of crude oil is good news for India

Q. What kind of rate cuts are you expecting?

While many in the markets are expecting deep cuts of 100 basis points or more in 2015, we expect just two 25-basis-point cuts, one in early 2015 and the other towards the end. In this context, the measures already taken to contain inflation and the existing lower inflation environment do not matter. It’s all about inflation expectations, which will come down only if the existing low inflation environment persists for some more time. Contrary to popular belief, it isn’t the RBI’s responsibility to manage short term economic sentiment; it is to ensure inflation and, more importantly, inflation expectations remain subdued. As inflation expectations come down, the RBI will be in a more comfortable position to cut rates.

So, if the market has already priced in a 100- basis-points reduction in rates, we will see some volatility going forward as these expectations get realigned to existing reality.

Q. How seriously should investors take this oil price fall?

At this point, there doesn’t seem to be any indication that global oil prices will start moving up. There seems to be oversupply which is supported by Opec [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] and Russia because they are, by far, the most efficient oil producers. Most Opec countries can still make a profit at $20 a barrel, which is not the case for shale gas or a lot of other alternatives. If Opec continues to hold production, you might see prices coming down further. However, any further fall will be tempered by shale gas capacity becoming unviable. I don’t see oil prices falling below $40-45 per barrel and sustaining for a long period. This $45-60 range for the foreseeable future seems to be where prices will remain unless there is a geopolitical shock.

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Q. Assuming this range remains or goes to $70-75… how does it help India?

India is a large net importer of oil so any drop in prices helps. It reduces our import bill and increases discretionary consumption funds in the economy. We need to look at the fall in oil prices by dividing countries into three parts: First, net importers who will benefit from low prices. Second, countries with a net balance that will remain neutral irrespective of prices; if they are producing all that they need for domestic demand, as international prices come down, the income of their oil producers falls, but residual income of other residents rises, so it balances out. The third are oil exporters: Large net exporters of oil will lose from the fall in oil prices.

India is in the first category and stands to gain in terms of lower current account deficit, lower inflation and lower fiscal deficit [which mirrors closely to our current account deficit].

If oil prices remain subdued, discretionary income stays in the hands of individuals and consequently, consumption increases, then revenues will pick up. It’s all connected.

Q. People say there is a global slowdown in growth and that’s not good for India. Do you think this fall in oil prices can fuel domestic growth?

There are two factors at play as far as the Indian economy is concerned—the oil imports where India stands to benefit, and global slowdown that will hurt. India is a very large exporter of services, manufactured goods, etc… more than 30 percent of our economy is exports. So, if there is a slowdown in external demand growth, this 30 percent of the economy will suffer.

What we’re looking at is: Does the fall in oil prices and its consequent benefits have the ability to even out the fall in 30 percent of the economy?

If the benefits of lower commodity prices are passed on to the economy fully, domestic demand should be in a position to more than compensate for the global slowdown.

Q. While oil prices are falling, rates of other commodities are also falling. Rural India supported itself on higher agricultural commodity prices. Will falling commodity prices have an impact on that economy?

We have seen a fall in prices of minerals and oil, but not of agricultural commodities. While it is possible that foodgrain prices may not rise at their earlier pace, there is no indication that they will fall substantially. Foodgrain prices aren’t as closely linked to global growth as prices of other commodities. For example, when the global economy is growing at a fast pace, demand for other commodities increases and vice versa. But people still need the same amount of food regardless of the level of growth. In fact, this demand only keeps growing as global population increases.

However, the monetisation of many agri-commodities through the ability to hold these in paper form, as opposed to physical form, has given rise to additional demand that did not exist earlier. If this monetisation were to reduce in response to a slowdown, it will unlock some additional supply that can cause these prices to fall as well. But it’s not going to be an equivalent correction if you were to look at minerals and oil, which are a different matter altogether—they’re industrial raw material and directly linked to economic activity.

Q. You feel that one should not get worked up…

Firstly, if there is a softening in soft commodity prices [agricultural products], the rural poor stand to benefit. A very large cross-section of this rural poor consumes more of these commodities than they produce. The only people who stand to lose are the larger farmers who sell surpluses. The smaller farmers who do subsistence farming won’t suffer. Secondly, if the benefit of lower oil prices starts percolating through the economy, costs will fall. This will benefit the rural poor as well.

(The interview took place before RBI reduced the repo rate by 25 bps on January 15, 2015.)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)