Extract from 'Editor Unplugged': The people Vinod Mehta admires

In the second volume of his memoirs, veteran editor Vinod Mehta lists the people he admires

“I tend to stay away from heroes,” Vinod Mehta says in the second volume of his memoirs. And later in that chapter: “Instead, I admire. Admiration is preferable to unrestrained adulation. With the former you have the luxury of choice. You can pick the quality which appeals to you—and ignore the blemishes. A person you admire has no obligation to claim Utopian stature; in fact, he could be part-charlatan with compelling redeeming features.”

He then names the traits he looks for (a short list: Integrity, courage (physical), courage (moral), fidelity, humour and impatience) and then an equally short list of people who meet those criteria. Here are extracts from that chapter.

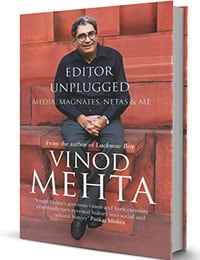

Editor Unplugged: Media, Magnates, Netas and Me

Author: Vinod Mehta

Publisher: Penguin Books India

ISBN139780670086498

Price: Rs 599

Pages: 300 pages, hardback

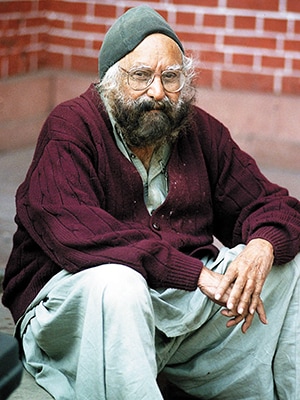

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

A small, modest, ground-floor flat in Juhu was his home and, on the first floor, a tiny cubbyhole served as his workplace. It was in the cubbyhole that we used to meet.

There were no chairs, only mattresses with cushions in the makeshift study. One sat next to him on the floor. He had no writing table, just a raised wooden platform with numerous nib-pens and inkwells, both red and blue. (He used red ink for exclamation marks, something he had a weakness for.) And, of course, the cubicle was full of clippings, periodicals, books and postcards. On the walls were displayed signed photographs of himself with Khrushchev, Tito, Nasser, Nehru. Despite the clutter it was not an untidy room. A chaiwala brought oversweet tea in glass tumblers at regular intervals—that was the extent of his hospitality. To say he lived frugally would be superfluous; he was a communist, even if linked to the glamorous film industry.

From this cubicle he wrote, directed and produced fourteen flop films. And scripted Raj Kapoor’s iconic Awara, Boot Polish, Shri 420, Jagte Raho, Bobby, Mera Naam Joker and many others. He also published sixty books, fiction and non-fiction. He was a busy communist.

Forever in debt and forever scrounging around for money, he borrowed from friends and moneylenders. All the films under his banner, Naya Sansar, were not minor box-office disasters but gigantic box-office disasters. ‘Some people say I am mulish, trying out themes of social realism without compromise,’ he explained. ‘“Give the people what they want,” they advise. But I believe in doing what satisfies not only my personal ego but also my social conscience.’

Abbas’s films would start promisingly. Sadly, after the first half, he would slump into sermonizing, making his cinema didactic and tedious. Fully conscious of the hazards of mixing propaganda and entertainment, he persisted. ‘All the money I make from Raj Kapoor, I put into my flops,’ he joked. He admitted history would remember him only as the producer who introduced Amitabh Bachchan to Bollywood (Saat Hindustani), a fact Amitabh himself acknowledged, saying if Abbas had not given him a break, he would have gone back to his boxwala executive job in Calcutta.

He worshipped Jawaharlal Nehru and lovingly recalled all his meetings with Panditji, especially the last one at Teen Murti, a week before Nehru passed away. As Abbas walked up to greet him, Nehru, weak after his stroke, tried to get up from his chair. Abbas urged him not to bother. ‘Abbas, I may be about to die but I haven’t forgotten my tehzeeb (culture).’ When he recounted this story his eyes welled up.

I remember him for his loyalty to a wonderful romantic vision, and also the lunches he bought me. On the first of the month he would collect his monthly salary of Rs 500 from the Blitz office and treat me at the Jehangir Art Gallery restaurant, Samovar. ‘You can have beer if you like,’ he would say. ‘Today I have money, tomorrow I won’t.’

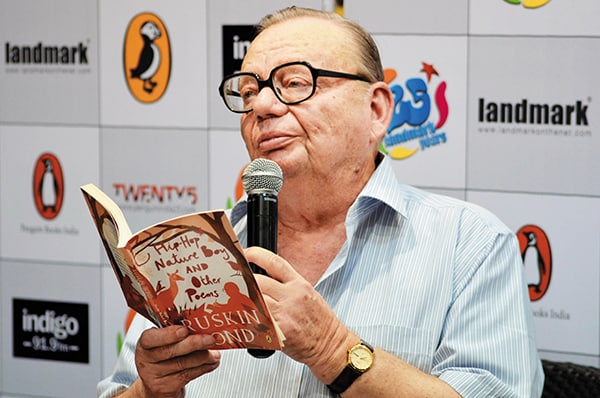

Generosity defined him. In four decades of friendship with Ruskin, several opportunities came my way to witness his extraordinary kindness to people who were strangers or just minor acquaintances.

For me, however, generosity is not his principal virtue. I admire him because he is the only person I know who is totally without envy; it is an emotion incompatible with his temperament. Till today, I cannot remember Ruskin ever badmouthing or maligning or criticizing any person, living or dead.

Now, writers, however talented, are generally mean, vindictive people. Some are misanthropes. Their interpersonal feuds are the stuff of legend. (The feuds mostly are the result of a ‘bad’ review.) When a fellow author produces a critically acclaimed book it drives them nuts. V.S. Naipaul, who received an indifferent notice from Salman Rushdie for one of his non-fiction works, told me in all seriousness, ‘I think Khomeini’s fatwa [against Rushdie] is a very good idea.’

And then we have Ruskin Bond, living in the hills since 1963, happily praising and endorsing an author living down the road or in another city. The besetting vice of ruthless competitiveness is missing from his DNA. He will go the extra mile to advise and encourage established and novice writers.

In his native place he is something of a ‘monument’ the visitor must see. At Ivy Cottage, the round-the-clock homage can become annoying, an avoidable disruption to his writing schedule. He occasionally complains about this intrusion, but with his trademark congeniality. His friends and buddies are strategically placed all over the state of Uttarakhand. For them he is no lionized ‘do not disturb’ man of letters, but merely Ruskin or ‘our’ Ruskin, someone who is always ready to extend a helping hand. A fifty-ish widow, well past her best days, calls up Ruskin. She has a problem for the writer to solve. ‘I need a man, Ruskin, do you know anyone?’ To which Mussoorie’s foremost problem-solver replies, ‘Well, I am here.’ How he finds the time to write, given his Agony Uncle duties, is a mystery.

If you live in the chaos and mayhem of Delhi, where residents kill for parking place, where women are gangraped in buses, where road rage leads to bloody heads, where the daily duplicity of our rulers is a commonplace, one can be excused for settling into a state of perpetual melancholy. Then you read Ruskin Bond effortlessly describing the joys of nature and the beauty of Mother Earth, and you are transported into another world. Tranquil, quiet, calm, charming, unhurried, gentle, optimistic, simple yet not simplistic, Ruskin Bond’s universe and Ruskin Bond’s identity are one and the same. You couldn’t have one without the other.

Fifteen years ago I bought a small cottage in Mussoorie. My wife was curious. Why Mussoorie, she asked, why not Shimla or Kasauli? I gave her no answer, but I knew why: I wanted to live close to Ruskin.

Sachin Tendulkar

During the period Sachin wore flannels, Indian cricket struggled through a quagmire of criminality and misbehaviour by some top names wearing the Indian blazer. There were personality clashes inside and outside the dressing room. There was the match-fixing scandal. Desperate attempts were made to trap Sachin in the smear campaign, especially by Pakistani player Rashid Latif, who accused, ‘Question Sachin, he knows everything.’ It was the only occasion Sachin felt the need to make a public clarification. He responded: ‘I have always been out of this kind of thing. The nation knows I am clean. My whole career has been transparent.’ There were stories galore of the Indian team’s womanizing, adultery, gambling, fights at parties... Sachin, miraculously, stayed out of the dirt. He was a model cricketer on the field and a model cricketer off the field.

The one time he came close to a display of bad sportsmanship was at Port Elizabeth in South Africa in 2001. Match referee Mike Denness handed him a suspended one-Test ban for ball tampering. The decision by the referee was widely criticized. That is the sole incident I can think of in an otherwise blemish-free twenty-four-year career.

It is a banality, but applied to Tendulkar it is wholly relevant: when Sachin walked on to the field he carried with him the expectations of 1.2 billion fans. These fanatics refused to accept failure. He had a mandate to perform and perform. Anything else was treason. Can you imagine going out to bat in Eden Gardens, Calcutta, with 90,000 excitable Bengalis shouting ‘Sachin, Sachin!’? A century or a double was the least they wanted. The demands were so unreasonable, the pressure they put on him so intense, it is a wonder Sachin retained his sanity. Tennis player Sania Mirza said, ‘The one salient thing that distinguishes Tendulkar from his contemporaries is the pressure we’ve put on him right through his career. He is expected to serve a ton every time he walks out to bat. Anything less is unacceptable.’

In 1989, when Tendulkar arrived on the international stage, India’s reputation for being ‘second rate’ in everything the country did or produced was well established. We provided and created most goods and services other, more developed, nations did without matching, or even trying to match, say, Japanese or German standards. In cricket, too, we turned out players of exquisite but erratic capability.

Simon Barnes writing in the Times (London) noted, ‘There are some big things to be written on Sachin as a living symbol of India’s headlong charge into the modern world. He is a validation, a living emblem of the truth that an Indian can be the best in the world, the best ever, if you like, and can do so without appearing to break a sweat and without needing to ask anybody for any favours.’

Years before economic reforms kicked in, Sachin Tendulkar’s prodigious talent and world-class competitive spirit showed India how to become a global superpower.

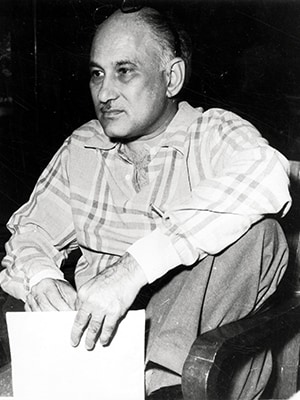

Johnny Walker

For me the sight of Mr Johnny Walker on the screen led to instant chuckling. ‘God gave me a face that makes people laugh, how could I go against His wishes?’ he once said.

I include Johnny Walker in my list not because of his matchless comic artistry. In the grim and gloomy India of the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, when the majority of the population was unsure of two square meals a day, he made people forget, for an hour or so, their daily miseries. He made citizens crushed by the weight of living, laugh.

His life story is typical. Vegetable and fruit seller, ice-cream vendor, stationery goods salesman, BEST bus conductor. This is how he began. It was on a bus, while he was amusing passengers, that Balraj Sahni spotted him. He recommended him to Guru Dutt, who sort of adopted him and changed his name from the tongue-twister Badruddin Jamaluddin Kazi to Johnny Walker, on account of his proficiency in drunken scenes. Journalist Sagarika Ghose described him in Outlook as, ‘The gentle balladeer of social change, he was the subaltern fool who sang as he suffered.’ Like the court jester in some of Shakespeare’s plays, Johnny Walker’s humour concealed bitter truths.

I do not wish to unnecessarily intellectualize a simple, poorly educated man’s craft and comic brilliance with gobbledygook. To compare Johnny Walker with the actor he ‘worshipped’ (Chaplin) would be both preposterous and pretentious. Even in India he did not achieve legendary status. He never shot a scene comparable to Chaplin eating a boiled shoe like a river trout in The Goldrush (this sequence is widely acknowledged as the funniest in cinema history). Nevertheless, for tens of millions living in the subcontinent, he was the comedian of comedians. No one else, in an admittedly lean field, comes close to matching him. He was extremely proud of his ability to make audiences laugh without ever resorting to a single vulgarity or double-entendre. In the 300 films he made, the Censor Board did not cut even one line.

Producers and directors insisted on at least one song being picturized on him solo, for which he was paid extra. Of the numerous songs he enacted, usually in the voice of Mohammad Rafi, I will pick my favourite. It comes from the film CID (1956) and was written by the leftist progressive Urdu poet Majrooh Sultanpuri. You’ve guessed it: Yeh hai Bombay meri jaan. Majrooh’s underappreciated lyrics, sung by Rafi and performed by Johnny Walker strolling around the latest symbol of the republic’s modernity, Marine Drive, captures just the right mix of frivolity and pathos prevalent in newly independent India. Crucially, it also shows up the deficiencies in Jawaharlal Nehru’s ‘tryst with destiny’, promising his countrymen and women the basic necessities of life.

When I was fifteen years old, I had no idea of the social and cultural significance of Johnny Walker. Then I saw him only as an incomparable comic actor of Hindi cinema. Now, a little wiser, I see him for what he was: the entertainer who by his acting genius helped millions of dejected and disappointed ordinary folk cope with the grind of daily existence.

Khushwant Singh

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, he frontally confronted Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. This was at a time when the Khalistan movement was at its peak. And Bhindranwale had metamorphosed from a humble preacher to executioner-in-chief, primarily of Hindus. Not just in Amritsar, but also in the entire state of Punjab, he and his followers spread tyranny and terror. Killings, bank robberies, extortions, hijacking of planes were a commonplace. In Khushwant’s words, ‘Bhindranwale discovered the easiest way of preventing absorption of the Khalsa into Hinduism was to create a gulf between Sikhs and Hindus. For a while he succeeded.’ No one in Punjab had the guts to speak against the fiery preacher.

Khushwant said he was the only Indian to challenge Bhindranwale. I cannot confirm the claim. However, he was without doubt the only Sikh to go after the perverse preacher. Even by Khushwant’s standards of calling a spade a spade, he went for him mercilessly. He described Bhindranwale as a ‘homicidal maniac’, he called him a ‘murderous killer’, he called him ‘primitive and uncouth’. And he warned the Sikh community, ‘Bhindranwale will be your funeral. He is taking you to your ruin.’

Unused to any criticism, the preacher reacted furiously. He threatened to wipe out Khushwant and his entire family in Delhi. As a result, Khushwant was under high-level police protection for fifteen years. Despite the very real threat, Khushwant did not dim the frequency or the ferocity of his attacks.

On Operation Blue Star (1984), his position altered completely. He was vehemently opposed to the Operation, calling it Indira Gandhi’s ‘tragic miscalculation’, and returned his Padma Bhushan.

Now, this is where I come in. When the attack on the Golden Temple took place, I was editing the Sunday Observer in Bombay. Among my regular contributors, the most valued was Khushwant Singh. I do not have an absolutely clear memory of the facts, but I must have criticized Khushwant for returning his Padma Bhushan. Let Khushwant take over from here. ‘Among the people who condemned my action was Vinod Mehta, the editor of the Observer. He wrote when it came to choosing between being an Indian or a Sikh, I had chosen to be a Sikh. I might as well have asked Mehta in return, are you Hindu or an Indian? Hindus do not have to prove their nationalism. Only Muslims, Sikhs and Christians are required to give evidence of their patriotism.’ He withdrew his column from the Observer, and for a few months, a frisson existed between us. It didn’t last long.

An editor needs no special consideration for facing danger and peril. It comes with the baggage. You can lose your job at twenty-four hours’ notice. You and your family can receive extreme abuse not fit to be reproduced in these memoirs. You can be pressured to compromise on an issue you feel strongly about since you also carry the responsibility for the livelihood of your staff. Khushwant, I am sure, faced these kinds of challenges—and worse. He did not flinch. The courage he demonstrated in taking on a murderous psychopath like Bhindranwale is something else.

Arundhati Roy

For me it has been a pleasure and a privilege to have been the editor who published almost everything she wrote since her first piece in Outlook in June 1998. Arundhati’s essay ‘The End of Imagination’ appeared in the magazine when bomb euphoria in the country was at its height. Her ferocious public attack on the BJP government going nuclear constituted the sole voice of sanity. Yes, it was 8000 words. Since then, whenever an Arundhati Roy piece is expected, a big cheer goes up among the editors and a small sigh among the sub-editors—they know a tough customer will soon be calling.

Arundhati chooses the title of her article, the introduction, the quotes, the pictures. She corrects page proofs sitting for hours in our conference room. She is a sub-editor’s nightmare! While she is unfailingly courteous when asking for whole pages to be redone, it would be dishonest on my part not to divulge that her departure from the Outlook office is welcomed on the floor where the sub-editors sit.

Conventional wisdom has it that anything above 2500 words puts the reader to sleep. Arundhati Roy taught us otherwise. Just as I was getting used to 8000-word essays, Arundhati produced a 20,000-word piece, ‘Walking with the Comrades’, on her three-week travels with tribals and Maoists in the liberated areas of Dantewada. The office was in a tizzy. How were we going to accommodate a commentary of this length? After much deliberation, I decided to carry the piece in full. It turned out to be the best editorial decision I have made. ‘Walking with the Comrades’, I believe, helped turn public opinion away from home minister Chidambaram’s shoot-them-from-helicopter-gunships bluster, to a more humane and realistic approach. The essay evoked the kind of response neither I nor Arundhati had anticipated.

She stays absolutely alone, except for a morning maid, and relishes it. I cannot imagine her living with someone. She is the original loner.

In India’s quarrelsome activist and writing community, she is not short of enemies. Pankaj Mishra is spot on when he says, ‘The hostility is so feverish because they feel betrayed. The woman the elite of India once declared their literary icon turned rogue and, more to the point, turned on them.’ She is regarded as sanctimonious, pompous, holier-than-thou; she contributes ‘nothing to public debate other than cooking up a controversy in which she is the central player’. To all of which she counters, ‘I am hysterical. I am screaming from the bloody rooftops… I want to wake up the neighbours, that’s my whole point. I want everybody to open their eyes.’

For myself, I am happy to misquote Voltaire, ‘If Arundhati Roy did not exist, we would have to invent her.’

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)