How companies deal with the too-much-cash conundrum

Some companies are facing a developed world problem—cash far in excess of their needs. How should investors interpret this?

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

In 2010, when Ajay Piramal, chairman of the Piramal group, sold the domestic formulations business of Piramal Healthcare to Abbott India for Rs 17,500 crore, investors and industry watchers lauded him for his success. But behind closed doors, many wondered if his group’s flagship Piramal Enterprises could judiciously deploy the mammoth cash it had received.

Piramal took his time in deciding what to do with the cash pile and proved himself to be a shrewd businessman. His acquisition of an 11 percent stake in Vodafone India in 2012 and its subsequent sale two years later yielded returns of 50 percent. Piramal also picked up stakes in the Chennai-based financial services major Shriram Group, in various phases starting 2014, and at a time when the real estate industry is in the doldrums, he’s lending money to cash-starved realtors at high rates of interest. To shield himself from a default, Piramal has ensured he has the first call on collateral assets.

Such business acumen, however, is more an exception than the norm. The question of what a company should do with the cash on its books has been a bugbear for those who run cash-rich companies and their investors. “I would argue that all cash belongs to the shareholders and should be returned to them if a suitable use cannot be found,” says Kenneth Andrade, founder and portfolio manager at Old Bridge Capital.

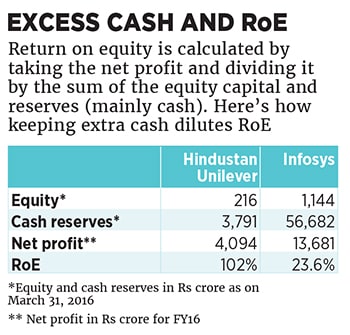

The purists will argue that any cash that cannot be deployed at high rates of return must be returned to shareholders, otherwise it dilutes the company’s return on equity or RoE (see table). High levels of cash have until now not been a problem that Indian companies (barring those in the information technology sector) faced. But sluggish growth and low payout ratios (the proportion of earnings a company pays out as dividends to shareholders) have meant that companies in areas as diverse as two-wheelers, FMCG and IT are sitting on cash they haven’t been able to deploy for a while.

So how should an investor interpret the cash on the balance sheet of a company?

Sanjay Bakshi, a professor at the Management Development Institute in Gurugram, argues that it is important to understand the management’s psyche. “Promoters with lots of cash often behave like kids in a candy store. The really good capital allocators demonstrate capital discipline by sitting on cash for a prolonged period of time, waiting for the right opportunity.”

In some industries, holding on to cash is a good idea. Take the cyclical metals industry for instance, where a prosperous up-cycle is inevitably followed by a brutal down-cycle. Here, companies that sit on cash would be at an advantage as they’d be able to pick up assets for a song when times are hard. Sadly, entrepreneurs in cyclical industries go berserk when times are good. Case in point: Hindalco’s acquisition of US-based Novelis for $6 billion and Tata Steel’s acquisition of the Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus for $12 billion. Both companies overpaid for the assets at the peak of the commodity boom in 2007. The current down-cycle has hit them hard.

At the other end of the spectrum are India’s IT majors, who have long faced investor flak for their excessive cash reserves (Rs 2 lakh crore by some estimates). Wipro, for instance, had reserves of Rs 44,000 crore and TCS Rs 64,000 crore as on March 31, 2016. They’ve argued that it is a war chest for a potential acquisition or to survive a sudden change in business model.Anup Maheshwari, chief investment officer at asset management company DSP BlackRock, believes that these companies will privately admit that there are no good acquisition targets on the horizon and stocking so much cash is unnecessary. He points to global consulting firm Accenture, which returned $4 billion to shareholders in FY16 through dividends and share repurchases to investors and saw its valuation rise.

“Over the last couple of decades, we have increasing discomfort with the fact that software firms have been hoarding a lot of cash for reasons that have a low probability of materialising. It is misallocation of capital and dilution of capital efficiency. While the dividend payouts have improved, they still fall short of what they could be,” says Bharat Shah, executive director at ASK Group, which has assets under management of $1.4 billion.

In the last two years, two-wheeler companies Bajaj Auto and Hero MotoCorp accumulated Rs 12,750 crore and Rs 7,900 crore respectively as on March 31, 2016, which they are struggling to deploy. Bajaj Auto’s RoE has dropped from 67 percent to 40 percent over the last five years. Hero MotoCorp has deployed a part of its cash to expand in the South American market and so its RoE has stayed put at 52 percent. With their steady business models, there is a strong case for them to increase payout ratios, analysts say.

One sector that has opened up its cash chest to investors, through high payout ratios, is FMCG or the consumer goods companies. They are textbook examples of how one must generate cash and return it to shareholders in the form of dividends. Shah argues that a case can be made for even higher payout ratios. “Those firms that need working capital can be judiciously funded through borrowings, thereby raising the dividend payout ratio and improving capital efficiency in the form of RoE,” he says.

It’s a compelling argument but Bakshi cautions that some consumer companies are seeing their business model coming under threat from the upstart Patanjali Ayurved and so they will need the cash to shield their turf. It is therefore not surplus anymore.

While valuing companies, a mistake the market often makes is to blindly look at numbers and decide the business’s worth. For instance, a company sitting on cash in a cyclical business with an unsteady business model will have a low RoE, but if the entrepreneur is able to make an opportunistic acquisition during a down-cycle, that can change the numbers overnight.

Instead of calculating the company’s RoE, investors would do better to calculate the RoE of the business by excluding the excess cash and associated treasury income. If the business’s RoE is excellent and the entrepreneur’s track record inspires trust, then at the right valuation, you have a winner, explains Bakshi.

By that definition, Ajay Piramal deserves a podium place. Efficient capital deployment, along with long periods where he sat on cash, is something he has demonstrated, and benefited from, through the course of his career. In 1986, his Piramal Enterprises was worth Rs 7 crore. Over the next 28 years, all he raised was Rs 477 crore. But by spotting the right opportunity—he left the family textile business and entered pharma—and then deploying cash efficiently and returning it to shareholders, Piramal Enterprises’ share price has clocked a compounded annual growth rate of 34 percent since 1986. Clearly, firms trying to solve their surplus cash conundrum have a precedent in Piramal.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)