Impact businesses are attracting investments with healthy returns: Viswanatha Prasad

Enterprises serving the base of the pyramid require a high quality of governance and transparency

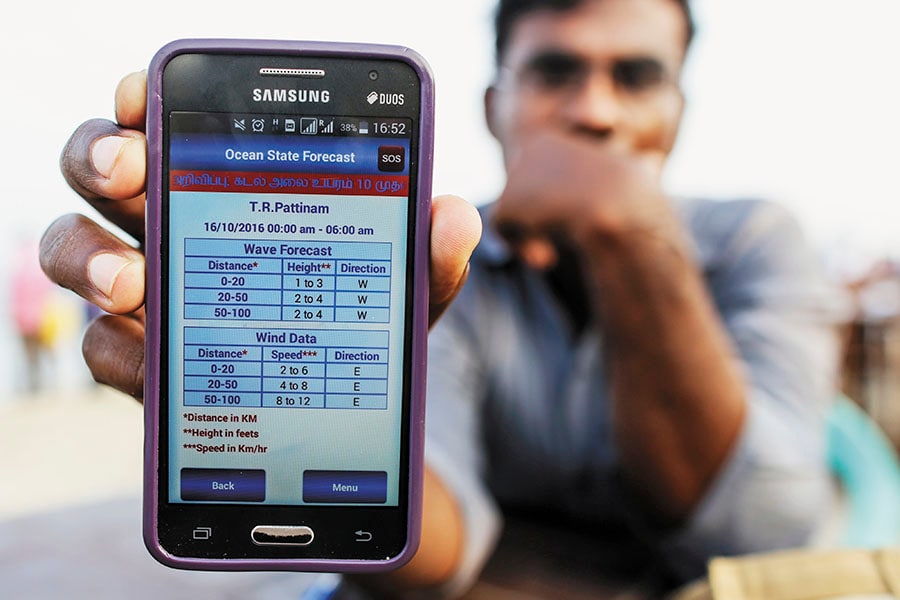

The country’s smartphone revolution has helped businesses reach the bottom of the pyramid and vice-versa

Image: Dhiraj Singh / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Businesses that tap a large number of customers in the lower-income bracket and are established with a clear social objective are increasingly becoming an attractive asset class in India, as they are globally. In India, while rural micro-credit, and then urban microfinance, saw growth and success over the last two decades, these businesses are now coming to the fore in a growing number of verticals and catching serious investor interest.

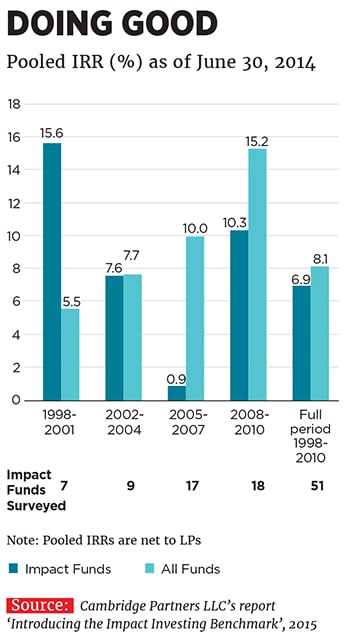

Impact investment is not philanthropy. Global data on funds established between 1998 and 2010 show that equity funds investing in these assets have shown healthy returns that are often less volatile than other assets. There have been years in which impact funds have outperformed normal funds and there have been years when they have lagged; generally, smaller impact funds have outperformed marginally.

Given the efforts of the Impact Investors Council (IIC), data gathering is becoming more robust in the industry and should help with benchmarking returns; a recent study—by an international consulting firm and the IIC—of impact funds in India is expected to confirm a similar returns trend.

From our experience at Caspian, there is evidence to show that these ventures generate dependable returns while innovatively addressing long-standing social challenges. Having invested over $100 million exclusively in impact businesses, and completing nearly two full exit cycles, we have built a strong case for continuing investments in such businesses. In recent years, we have seen financial inclusion companies in India perform very well despite several setbacks. They have proven to be resilient with agile and dynamic management. Investors, including Caspian, in small finance banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) that focus on small businesses have seen profitable and healthy exits.

Sceptics could argue that successes in financial inclusion cannot be replicated in other impact sectors. The same scepticism dominated the early years of financial inclusion, in the late 1990s. It was argued that what our extensive banking system could not achieve in over three decades could not be achieved by microfinance institutions either. They did, and quite spectacularly. More recently, we are witnessing early success in lending to small businesses, which is very different from microfinance. While new sectors will face some period of testing, they can also learn from the now-mature financial inclusion sector, and move more rapidly up the learning curve.

Today, impact businesses are on the rise, not just in financial services but also in areas such as education, affordable housing, health care, agricultural technology etc. Over the last four years, we have lent to more than 25 early-stage entities across these sectors, and, after evaluating more than 200 such companies, we are optimistic about the potential for impact in the other sectors as well.

In the Indian context, there are three factors that give impact investing a distinct advantage: First, the size of the market gives these usually low-ticket, high-volume businesses massive potential; second, our entrepreneurs have demonstrated the ability to work at scale by re-engineering products and services in a frugal manner that makes these accessible to low-income clients; third, and perhaps most important, we have a vibrant ecosystem of early-stage investors looking for such entrepreneurs.

However, an important caveat in serving customers at the base of the pyramid in India is that it requires exceptionally high-quality governance and transparency. Business models must deliver real value to clients while satisfying investors. An appearance of profiteering at the expense of the poor will invite criticism and backlash.

For instance, if someone builds a chain of schools serving the low-income segment and perfects the playbook for running the business profitably, critics could argue that the private school is exploiting households that would otherwise have sent their children to government-run schools for free. The argument that such a profitable chain will attract competition and hence bring prices down has not always worked, as this could take several years in a large and underserved market such as India.

The most successful impact companies in India are those that carefully build corporate cultures and governance rules to benefit both clients and shareholders. The recently publicly-listed Equitas Holdings and Ujjivan Financial Services are examples of such businesses.

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to measure, report and benchmark the effectiveness of these business models, and companies with strong governance seek out these metrics to guide and discipline themselves. Fund managers who invest in such impact enterprises are also measured and rated among their peers. I am hopeful that these will gain more traction and be made more relevant to the Indian context. So apart from an ability to execute to scale, the enterprise will also need to demonstrate high quality governance and be open to scrutiny, coupled with the ability and stamina to work with all other stakeholders over a sustained period.

Recent reports suggest that large firms, such as TPG Capital and BlackRock, are looking to make significant investments into Indian businesses that serve the base of the pyramid. At Caspian, we expect to invest $50 million in new investments over the next few years across multiple impact sectors.

The writer is founder CEO of Caspian Advisors, an impact fund based in Hyderabad

—As told to Harichandan Arakali

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)