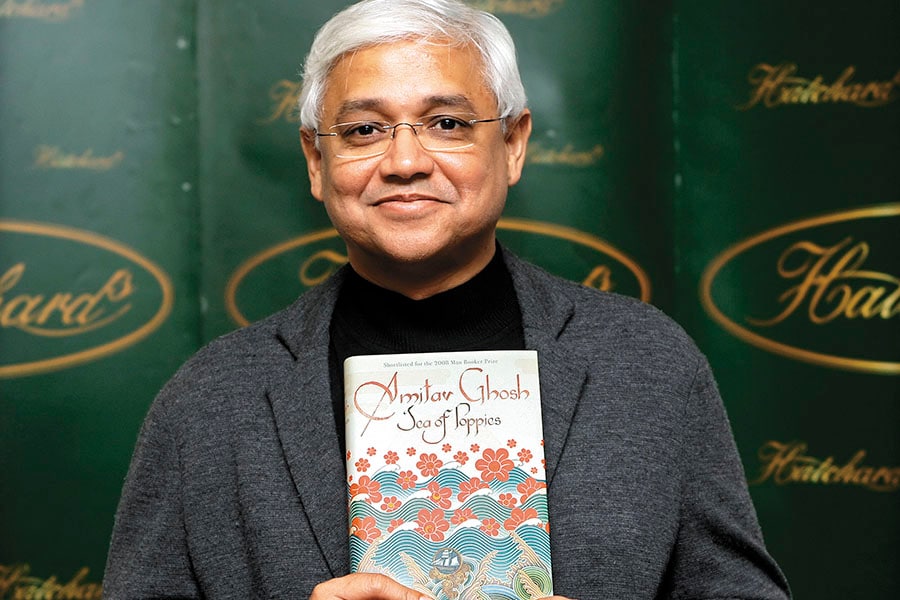

The world is going to have to rethink the existing refugee categories: Amitav Ghosh

Author Amitav Ghosh talks about political convulsions, his affinity for Bengal and the literature that emerges from it

Author Amitav Ghosh says while there are many fascinating aspects to the writing process, he usually finds the beginnings the most difficult to write

Author Amitav Ghosh says while there are many fascinating aspects to the writing process, he usually finds the beginnings the most difficult to write

Image: Barbara Zanon / Getty Images

Q. The land your characters inhabit—whether it is the Gangetic plains in Sea of Poppies, the Sunderbans in The Hungry Tide, or the Burmese forests in The Glass Palace—has formed an integral part of your narratives. Is this something you consciously include, or does it happen by itself?

It’s a difficult question to answer because to some degree it is conscious because you have to find out details of that kind. But it’s really conscious in the sense that it is part of a plan; these are things that interest me.

Q. In your stories, there is also a lot of movement where characters are concerned; they, very often, traverse different geographies. How does this come about?

That part of it is really a reflection of my own history. I have always been travelling and living in different places. And also it is the experience of my own family, which was originally from Bikrampur near Dhaka in Bangladesh. They left a long time ago, before Partition; some came to India, some of them went to Burma. These are reflected in my work.

But I have to say that when I started writing, to write about these movements was kind of unusual. Specially in the India context, people usually wrote stories that were set in one town or village or province. Very few people were writing about Indians who were migrating, going elsewhere, were displaced. Now migration is almost mainstream.

Q. A place like Bengal has historically seen so much displacement because of climate and topography. Do you think migrations such as these grab less attention than those caused by political reasons such as civil wars?

That’s an interesting question, and one that I also think about. The whole landscape of Bengal has always been unstable. It’s always been shifting. In some way, people have adapted to that; they have historically always been able to move. And we see this reflected in Bengali literature also. I think you are right that people pay less attention to it for that reason.

Q. Do you think migration due to environmental causes does not attract attention because it has been happening for so long?

Yes, definitely. And it is so unfair the way it is prioritised right now. In Europe, they now classify people who are moving because of environmental causes as economic refugees, as opposed to political refugees. So, it’s like political refugees are good, economic refugees are bad. In fact, often the circumstances are such that you can’t make that distinction. In the Syrian case, in the case of Darfur, you can’t really make that distinction between what is economic and what is political. I think the world is going to have to rethink all these categories.

Because, you know, the world is acting as if the only people migrating out of Syria, or through Syria, are Syrians. You look at the photographs, and you can see that a large part of them are South Asians. It’s strange how this whole thing is playing out.

Q. Is it Western thought processes, then, that label refugees in certain categories—thus compartmentalising them—and do not recognise the links between these categories?

You can’t really blame the Western governments; look at out how our governments have responded. After all, in West Bengal, which should, of all places, be sensitive to refugees, look at what happened in Marichjhapi. They [the government] massacred refugees there; all of them were then moved out to Dandakaranya [now in Chhattisgarh]. Our governments have not been particularly sensitive to these issues either.

[In 1979, the West Bengal government forcibly evicted thousands of Bengali, Hindu refugees, who had fled persecution in Bangladesh, from a cluster of islands called Marichjhapi in the mangrove forests of the Sunderbans. Although the exact number of casualties were not determined, several hundred refugees are believed to have died from police firing, starvation—following a blockade—and disease. Ghosh’s novel The Hungry Tide, set in the Sunderbans, is against the backdrop of this incident.]

Image: Leon Neal / AFP / Getty Images

Q. You have studied and lived mostly outside Bengal. What affinity do you feel for it?

Bengal was always where I went back to from various places. I can’t account for it, but I do know that it plays a very large part in my thinking. Not just its landscape, but also its literary tradition. I think my affinity for water, especially.

Q. Yes, in almost all your books water—whether it be rivers, seas, deltas and estuaries—form an integral part of the landscape, and the lives of the characters.

That definitely comes from Bengal. I find myself very much interested in the ways of life that come out of water. As soon as water appears, the question of regions and boundaries appears irrelevant. Water is fluid, people cross it. In his book [Crossing the Bay of Bengal, 2013], historian Sunil Amrith estimates that migration across the Bay of Bengal historically has been the single largest anywhere in the world.

Q. Would you say the fact that you have not really lived in Bengal affects your writing about the region?

I think it would. The fact that I don’t live there all the time definitely gives me a distance, which is, in some ways, good, and in some ways not so good.

It’s a strange thing… so little has been written in Bengali about the Sunderbans. It is a subject that is almost absent from Bengali imagination and literature. Even among Bengalis who love forests and the environment—they love temperate forests, they like mountain forests, they go up north, around Darjeeling. In their imagination, those are forests—and the Sunderbans are not really a forest.

Q. How are the Sunderbans changing? One chain of argument claims that there is greater connectivity that brings the islands closer to the mainland; another says that increased development is ruining the ecosystem?

There is an element of truth in both of those claims. But it’s actually more under threat from climate change than anything else. The populated parts of the Sunderbans have been devastated, most by cyclone Aila [in 2009]. People have left in large numbers; it’s contributing to all sorts of things in so many ways that we don’t even begin to see. For instance, the sex trade in Kolkata. If you go down the country’s western coast, you will see that the entire working class of the region is now Bengali. Most of them are from the Sunderbans. You will see this in Goa, for instance.

Q. Which part of your storytelling process fascinates you the most, and which part torments you the most?

The beginnings are the worst.

Q. Do you have the end in sight even before you begin?

No, no. The end appears somewhere, as you are struggling along. But the beginnings are what I find really difficult. I find that around 20 percent of the time I have invested in each of my books go into the first 10 pages.

Q. What is it that you struggle with? The settings, the characters?

It’s all those things. But I think the most is what the writer calls the voice: The way in which to tell the story; finding a form, and a style that is adequate to the story.

Q. What is the fascinating part?

There are so many. Discovering what your characters are going to do, where they are going to go.

Q. Does it surprise you to see that you have written something that you did not see coming?

Oh, all the time! That’s one of the great pleasures of writing. Different writers write in different ways. For me, it’s not as if I sit down and have it all mapped out, and go from point A to point B. I start the journey, and then there’s nothing but surprises.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)