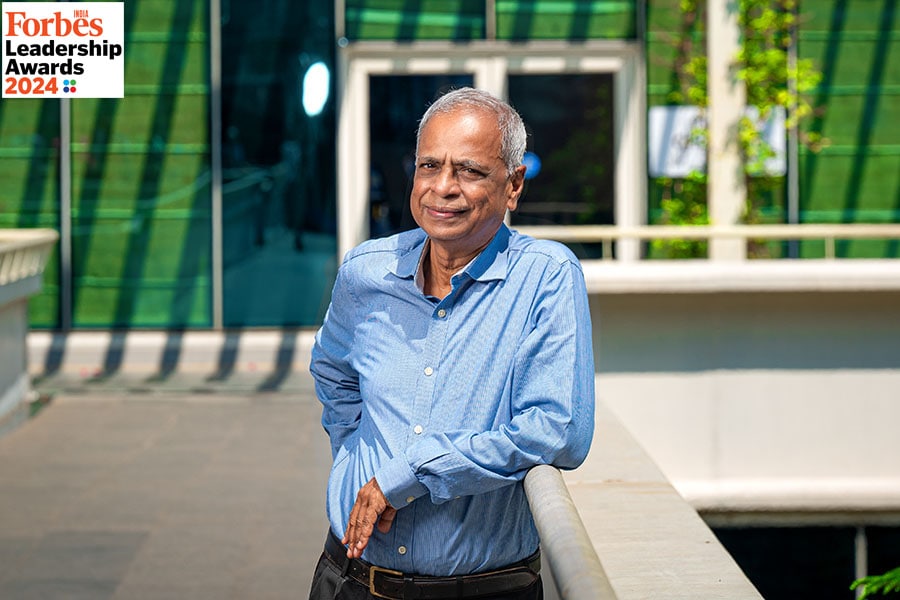

Padma Shri Ashok Jhunjhunwala: The deep tech doyen

Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala, winner of the Forbes India Leadership Award for Ecosystem Enabler, dreams of an India where world-leading hi-tech is built at home to always work for the masses

Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala, IIT Madras, President, IITM Research Park, IITM incubation Cell and RTBI

Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala, IIT Madras, President, IITM Research Park, IITM incubation Cell and RTBI

At one point, very early on after he came back from the US, Ashok Jhunjhunwala had thought he might need to get into politics to bring about the kind of changes he wanted to see in India. More than 40 years ago, it was an India where getting a telephone connection took years, with a waiting list of millions.

It was a good thing for India’s future deep-tech ecosystem that he quickly abandoned that idea, and instead joined the electrical engineering faculty at the IIT-Madras. He’s a graduate of IIT-Kanpur, with a PhD from America’s University of Maine.

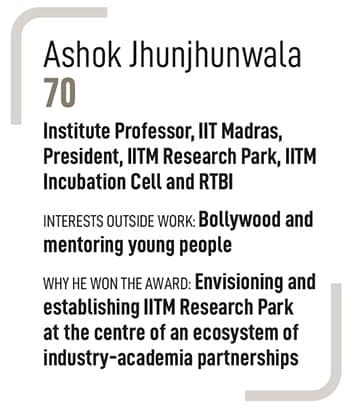

The 70-year-old Padma Shri awardee has many achievements under his belt, in areas ranging from wireless telephony to mobile banking to solar equipment, and battery swapping for electric vehicles. His most enduring legacy, however, is the IITM Research Park he conceived and helped establish, and where he continues to scout the next big deep-tech startup.

“Almost all companies are deep-tech companies. I don’t even remember if there is any ecommerce company. We want deep-tech companies that really can make a difference,” Jhunjhunwala says.

Promoted by the institute as a Section 8 not-for-profit company, the park has incubated about 350 tech startups, facilitated partnerships with some 150 Indian and foreign companies, and laid the foundations on which a vibrant deep-tech ecosystem can flourish over the next decade—the likes of which India has never seen.

The research park almost didn’t happen. For years, the powers that be told Jhunjhunwala that there was no land for it. A chance meeting, on a flight, with the then chief secretary of the Tamil Nadu state government around 2005, got Jhunjhunwala a short audience with the then chief minister, the late Jayalalithaa.

The research park almost didn’t happen. For years, the powers that be told Jhunjhunwala that there was no land for it. A chance meeting, on a flight, with the then chief secretary of the Tamil Nadu state government around 2005, got Jhunjhunwala a short audience with the then chief minister, the late Jayalalithaa.