From Mumbai to Goa, and Jharkhand to Kerala, the growing popularity of pickleball in India

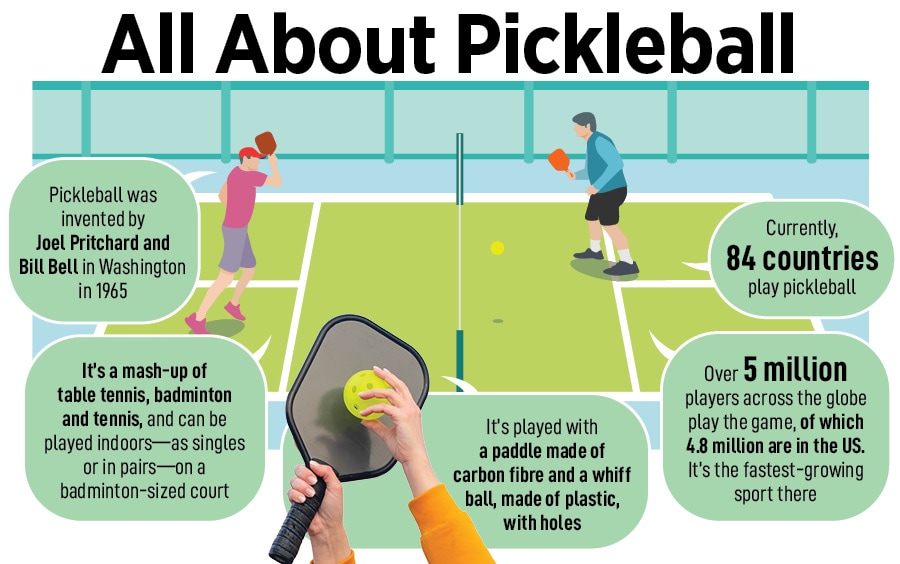

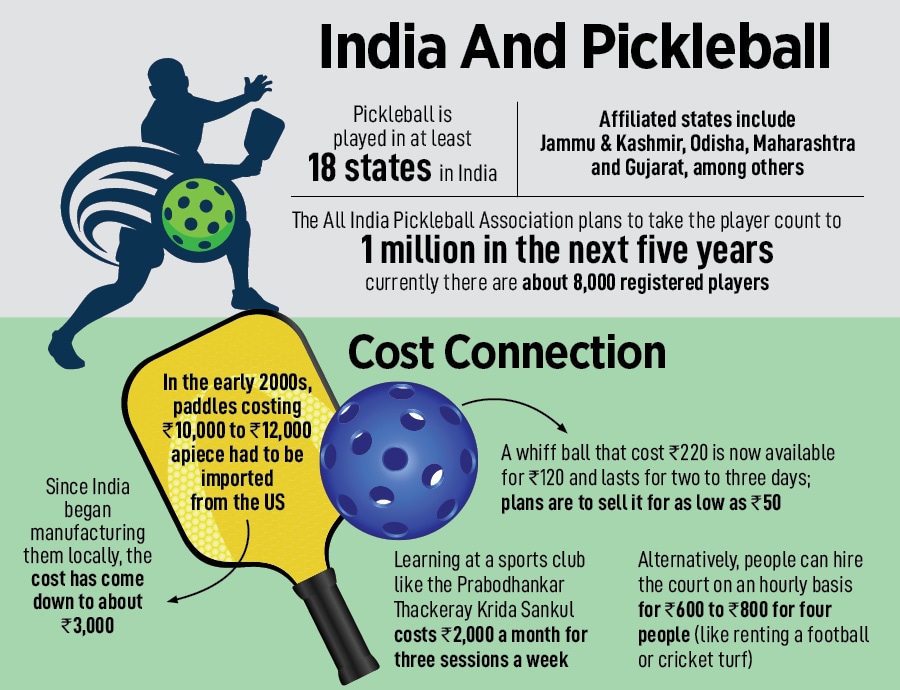

The non-contact game that combines elements of tennis, table tennis and badminton is seen as a recreational sport with health benefits. Its stakeholders are leaving no stone unturned to promote it at the grassroots with demos, local matches and big-budget tournaments

Pickleball players practise at the Prabodhankar Thackeray Krida Sankul in Vile Parle (East), Mumbai.

Image: Swapnil Sakhare for Forbes India

Pickleball players practise at the Prabodhankar Thackeray Krida Sankul in Vile Parle (East), Mumbai.

Image: Swapnil Sakhare for Forbes India

The pickleball arena at the Prabodhankar Thackeray Krida Sankul (PTKS) in the Mumbai suburb of Vile Parle (East) is oblivious to the commotion on the adjacent road on a dark, rainy evening in July. As people scurry for cover amid traffic chaos, a doubles game is on in full gusto on one of the courts—protected from the downpour by plastic sheets tied to bamboo scaffoldings—at the sports complex. A girl opts for a serve-and-volley only to be outsmarted by one of her opponents under white lights.

The coach nods in approval. At the court next to it, a group of youngsters warm up for their training session while two boys begin practising their backhand strokes.

A racquet sport that combines elements of tennis, table tennis and badminton, pickleball is growing in popularity across the country. People from the age of eight to 80 are playing the game—either for recreation, some sort of exercise or professionally—that was originally invented in 1965 in the US. In India, many discovered pickleball mostly during the Covid-19 pandemic as a non-contactable sport with health benefits, but the first efforts to introduce the game in the country began in the late 2000s. At the forefront of it all was Sunil Valavalkar, founder-director of the All India Pickleball Association (AIPA).

Passion for the game

Valavalkar’s first brush with the sport was in 1999 when he went to Canada as a project supervisor for the Indian government’s non-formal-educational youth programme. For over three months then, he lived with sports aficionado Barry Mainsfield, who played tennis in the morning, badminton in the afternoon and pickleball on the roads in the evening, “often lifting the net for the cars to go by”. “I played pickleball there, and returned to India in January 2000, but I forgot about the game. It was like another sport for me,” recalls Valavalkar, 59, who began playing tennis at the age of 40, got into sports administration in 2007, and is now wholetime director with GTL, an infrastructure services company focussed on telecom.