Indian luxe chocolates are having a moment under the sun

As the demand for craft chocolates rises, entrepreneurs are working with cacao farmers to improve processes

(Clockwise from top left) A cacao tree with fruits at one of the farms Manam sources from in West Godavari district; Soklet’s organic brewing cacao and arabica coffee; A cut cacao fruit shows the beans; cacao beans drying at Regal Plantations; Manam’s Indulgence collection

Image: Courtesy Soklet and Manam

(Clockwise from top left) A cacao tree with fruits at one of the farms Manam sources from in West Godavari district; Soklet’s organic brewing cacao and arabica coffee; A cut cacao fruit shows the beans; cacao beans drying at Regal Plantations; Manam’s Indulgence collection

Image: Courtesy Soklet and Manam

In 2015, Karthikeyan Palaniswamy, a textile entrepreneur from Coimbatore, got chatting with his brother-in-law Harish Kumar Manoj over ramping up revenues for Regal Plantations, the farm Harish’s family owned in Tamil Nadu’s Pollachi. Housed over 160 acres, Regal grew coconut, nutmeg and cacao, and Harish was brainstorming to see if the cacao, the raw ingredient for chocolates, which they had planted since 2003, could fetch them a higher value. “He was wondering if he should export the beans, and through such conversations came up the idea why not make our own chocolate?” says Karthikeyan.

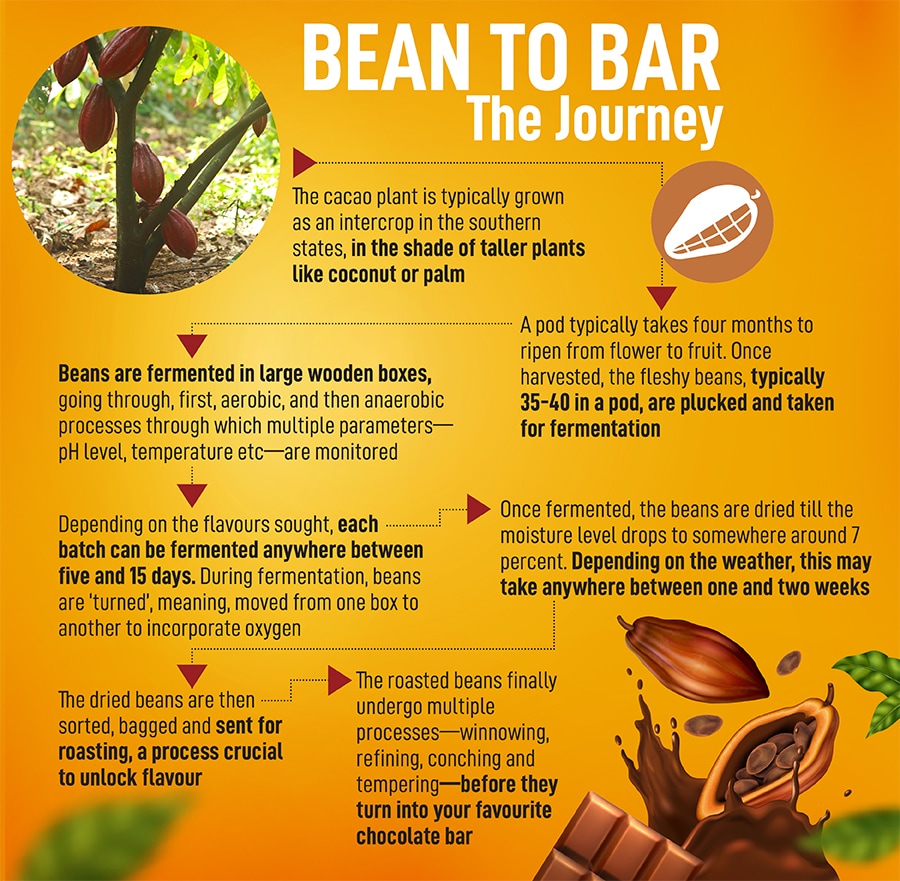

A bit of R&D and online tutoring later, they produced a bar, but the duo also realised the secret to good cocoa (the processed product) used in craft chocolates—small-scale, fine-flavoured chocolates—lies in the quality of cacao beans, and if they were to match global standards, they needed to benchmark themselves against top bean-to-bar makers around the world. Karthikeyan’s textile business often took him to the US and, on one such visit, he reached out to Dandelion Chocolate in San Francisco, which makes about $15 million a year by selling craft chocolates. “But they told us our beans were not good enough,” says Karthikeyan. “That made us pull our socks up. We visited a lot of farms around the world—in Indonesia, Vietnam—to learn how they harvested beans and the processes they set up to ferment and dry beans post-harvest. It took us one whole year to get these rolling.”

In 2017, at the Paris Salon du Chocolat, an annual trade fair for the industry, Regal was selected as one of the top cocoa producers in the world and received the International Cocoa Awards. Buoyed by the recognition, they launched their own brand, Soklet, in end-2017. From zero revenues that year, the company closed FY23 at ₹3 crore, and is hoping to cross ₹4 crore this year.

Regal also produces about 50 tonnes of beans a year, of which 35 to 40 tonnes are exported to Europe, the Middle East and Japan, among others. Bars made from these beans have received top awards at the International Chocolate Awards—French chocolatier 20°Nord 20°Sud’s dark chocolate bar with Regal’s Anamalai beans won the silver in the European region this year, while Japan’s Daito Cacao won the gold in the Asia-Pacific region blending Regal’s beans with those from Uganda.

“When they first came to us, they were under-fermenting the beans, which left woody and off flavours. But there were some good notes too, which told us we could work with them if they improved their processes,” says Ron Sweetser, cocoa sourcing and quality manager, Dandelion. “Now we buy about 8,000 to 10,000 kg of beans a year from them, pretty much the same average that we buy from other producers around the world.”