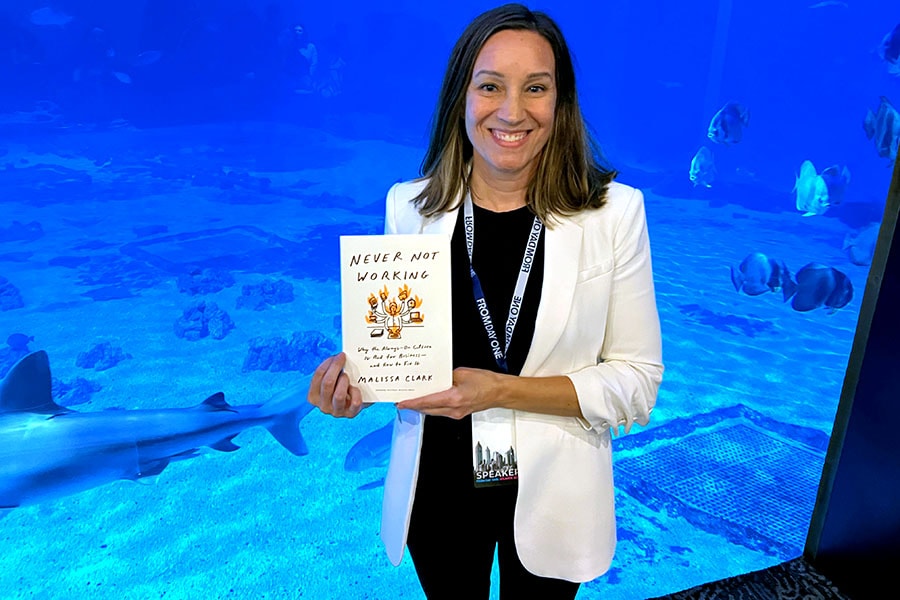

Celebrate those who work smarter, not longer: Malissa Clark

An 'always on culture' carries massive costs to both individuals and organisations, says Clark, who leads the Healthy Work Lab at the University of Georgia

Malissa Clark, an associate professor of industrial and organisational psychology at the University of Georgia in US

Malissa Clark, an associate professor of industrial and organisational psychology at the University of Georgia in US

Malissa Clark is an associate professor of industrial and organisational psychology at the University of Georgia in the US, where she leads the Healthy Work Lab. She is known globally for her scholarship on workaholism and worker well-being. In an interview with Forbes India, she talks about practical ways to choose balance over work obsession. Edited excerpts:

Q. Why a book on ‘workaholism’ now? How have the pandemic and digitally enabled workspaces impacted the trend?

In many cultures—India included—the pressure to be working long hours is not new. Unfortunately, it seems as though our relationship with work has gotten even more unhealthy in recent years with two key factors being the pandemic and technology.

The pandemic has affected our relationship with work in two key ways. First, there was a massive rise in remote work with many industries shifting to work from home practically overnight. I am a huge proponent of remote work, for a variety of reasons, but working from home blurs boundaries between work and home. It’s critical that employees working remotely establish physical and mental boundaries between work and home, such as setting up a home office or establishing habits that help to transition between work and home (for example, walk around the block at the end of the day).

During the pandemic, our communication patterns seem to have shifted. Data collected by Microsoft during the pandemic shows increased use of their platform in the evening hours compared to pre-pandemic in what they dubbed the “triple peak day.”

Q. Are some of us born work addicts or is it the cultural context that makes us so?

Workaholics often have certain traits that have been present throughout their lives. One is perfectionism—nothing is ever goosd enough. Another is overcommitment—always taking on too much and not knowing your limits. Workaholics also have problems with being idle.

At the same time, I think the cultural context we live in can absolutely reinforce or exacerbate our workaholic tendencies. For example, from a young age, many individuals are being taught that working hard is a way to prove our worthiness. The “ideal worker norm” is culturally endorsed, with the ideal worker being someone who is available 24/7 and who prioritises work above everything else, including their own personal well-being.

Q. What’s your perception of the scenario in India?

Workaholism is an even bigger issue in India than in the US due to the extreme cultural pressure to prioritise work commitments over personal commitments, and the highly competitive nature of the job market, resulting in pressure to work very long work hours. This plays out in the data on average hours per week, with India having the longest average work week of the ten largest economies globally.

Q. Are workaholics necessarily more productive?

No, they aren’t, for several reasons. It is well-documented that workaholics tend to overextend themselves and don’t leave time to recover. Recovery experiences—not just restful sleep, but also letting go of our work when we are awake—are an essential process that allows us to replenish the energy that we expended during the workday.

Workaholics also operate in constant fight-or-flight mode. They can also be difficult teammates and bosses, setting unrealistic timelines and causing unnecessary stress for others by overcommitting the team. They also may be more likely to engage in certain forms of counterproductive work behavior such as aggression and incivility.

Also read: How to combat an "always on" work culture

Q. What can we possibly do to kick our workaholic habits?

Conduct an experiment on yourself to determine your habits (for example, do you tend to “work lite”— incorporate work into non-work and relaxation activities?) Once you recognise these patterns, take steps to keep these in check.

First, redefine “urgent.” In reality, very few things are as urgent as we believe they are, and the best workers are those who can differentiate between the tasks that are truly important and urgent, and the tasks that can be completed at a more reasonable pace or delegated to someone else. Use your “to do” list as a way of prioritising and mapping tasks, instead of thinking of it as something that everything needs to be checked off before you stop work for the day. Ensure that you are adding a few important non-work items to the top of your list (e.g., taking an afternoon walk).

Tackle your workaholic thoughts. If you find yourself obsessing about work and having a difficult time “turning off”, try and find a mastery experience to divert your attention to. Mastery experiences are challenging (non-work) activities that stimulate and challenge your mind…and you are not simply sitting idle. Some ideas are learning a new language, developing skills in a hobby, or learn to play a new instrument.

Q. What are the cues of an overwork culture?

There are a variety of cultural artifacts that signal to employees what organisational leaders value. For example, how are new employees socialised? Are they taught to be in before the boss and to not leave until after the boss leaves? One woman I spoke with said she was taught early on that if she needed to leave for an extended period of time, she should only take her keys—leaving her purse and coat. This gives the impression she only stepped out for a moment, because long breaks during the workday were frowned upon. Another cultural artifact is the organisation’s reward systems. Who is being rewarded? Are these employees the ones who pull all-nighters and prioritise work over family, who spend many, many hours in the office? That sends a clear signal that overwork is highly valued and rewarded.

Q. ‘Always on’ to ‘optimally on’—how can organisations make this transition in culture?

Evaluate your team’s communication patterns to determine if there is a pattern of “always-on.” For example, do you and your team members send (and expect) responses to texts or emails sent after hours? How often do you do this? This type of after-hours communication exacerbates what Leslie Porter calls the “cycle of responsiveness.” The more communication occurs after hours, the more this becomes an expectation, and then there is increased pressure to respond, for fear of being left out or left behind. Research shows that when supervisors always respond quickly to text messages after work, subordinates feel strong pressure to also respond quickly. Organisations should consider leveraging their technology tools to break the cycle—for example, using software that automatically pops up when employees are trying to send an email after hours asking if they would like to schedule send for the next morning.

Q. Are four-day work weeks and predictable time-off good strategies?

I would love if we can reduce the number of hours in a workweek. Technology continues to help increase our efficiency and accomplish our tasks in less time. However, we have been stuck with the idea of a 40-hour, five-day workweek for a century. In 1926, Henry Ford’s introduction of the five-day workweek was seen as radical. Currently, the same can be said about the four-day week movement. Perhaps it’s actually not so radical after all, but long overdue.

Predictable time-off can be a way to make some headway in a hard-driving organisation. A good case study is offered by the intervention implemented at Boston Consulting Group (BCG)—see Harvard Business Review (HBR) article by Perlow and Porter (2009). An organisation that is “always on” cannot reasonably go from their current culture to a four-day week. However, change has to start somewhere, and sometimes what might be seemingly a small change (such as one predictable evening off) can make a big difference, and can be a way to start to change minds that it is possible to work differently.

Q. How can leaders be role model for non-workaholic behavior?

Leaders are in a great position to help reverse the always-available, work-first mentality. For starters, they need to be good role models for their employees. Show your employees it’s okay to fully disconnect during vacation by not responding to emails (and also use that vacation time). Leave work early for your kid’s sports game and embrace this, instead of hiding it. Re-examine your team’s communication patterns and look for ways to break the cycle of responsiveness. For example, have you gotten in the habit of texting employees or emailing after hours? Instead, schedule send that email so it arrives during work hours. Respect your employees’ boundaries. Reward working smarter, not longer.

Q. Who’s an ideal worker and what makes for ideal workplace in the present scenario?

Focus on output, instead of input. Stop using long hours as a measure of good performance. Reinvent what the ideal worker is. Currently, we view the ideal worker as someone who prioritises work above everything else, who puts in long hours, and is always available no matter the day/time. Let’s celebrate employees who produce good product but also take care of themselves and their own well-being. Let’s celebrate those who work smarter, not longer. The first one in and last one out is often the one rewarded and celebrated.