With an extensive 3rd wave, will be naive to expect business would be as usual: Abheek Barua

Two vicious Covid-19 waves have likely taught Indian companies how to handle disruptions and bottlenecks. But if Omicron spins into a debilitating third wave, it will throw both businesses and economic growth into a flux, the chief economist and executive vice president of HDFC Bank writes

The somewhat soft inflation numbers in the third quarter of 2021 are likely to be transitory

The somewhat soft inflation numbers in the third quarter of 2021 are likely to be transitory

Image: Balaji Srinivasan/ Shutterstock

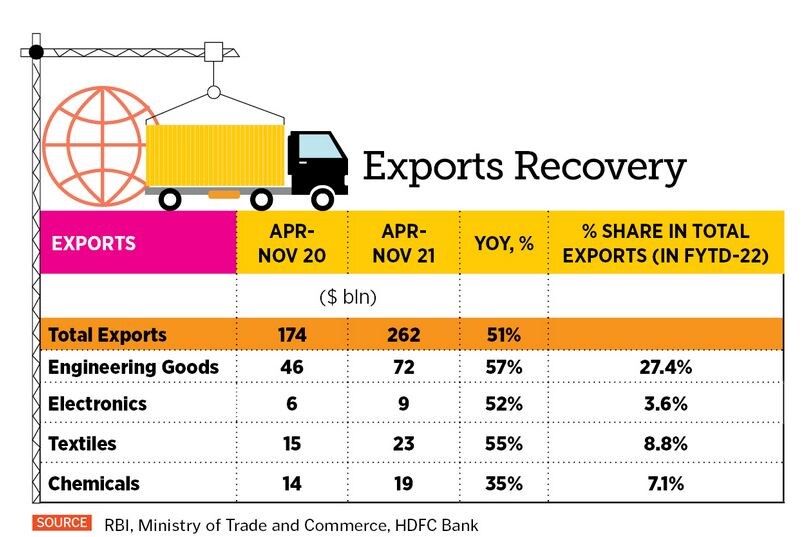

The Indian economy has rebounded sharply in 2021-2022 from the depths it found itself in last year. Unless there is a massive third wave of Covid-19 riding on the Omicron variant, it seems poised to expand by at least 9.5 percent. There was a certain inevitability to this sharpness of the rebound. Simple arithmetic would suggest that when income levels go back to normal after a sharp contraction, growth rates are likely to look quite spectacular. Add to this the fact that the contraction was driven by forced curtailment of economic activity (most importantly, the activity of purchase and consumption) to contain the spread of the virus, and you get a situation where pent-up consumption needs to unfurl as the economy reopens, giving growth a pop.

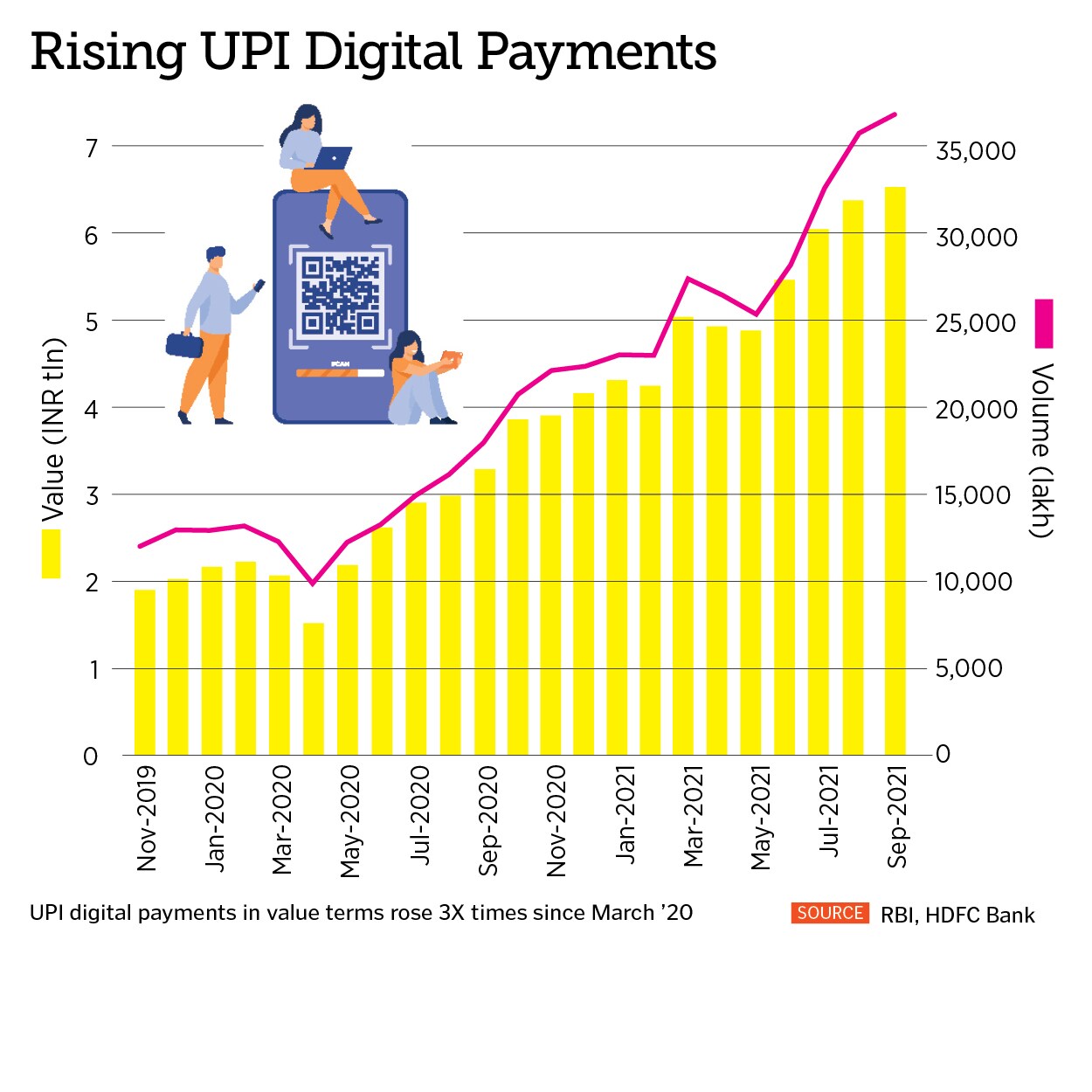

However, to see the recovery either as purely a mathematical chimera or merely the release of pent-up demand is misleading. A number of things have happened during the two years of Covid-19. Both the digital economy and platform-based delivery services have seen significant expansion. Due to the compulsion of going digital as containment measures restricted mobility, fintech and edtech, for instance, saw a step-jump.

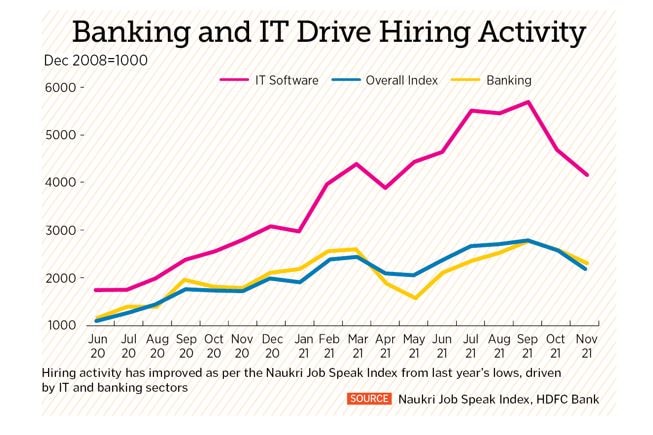

IT companies shifted seamlessly to remote working and saw a rise in demand for their services as, globally, companies focused on cutting costs. With business expanding, companies in these sectors have been on a hiring spree, resulting in higher salary escalation and spending. The banking and financial services industry has joined in anticipating rising business. These have helped consumer demand and could sustain.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)