An uncertain rural boom

While a few rural numbers may have looked up in June, it is too early to call this a broad-based demand uptick

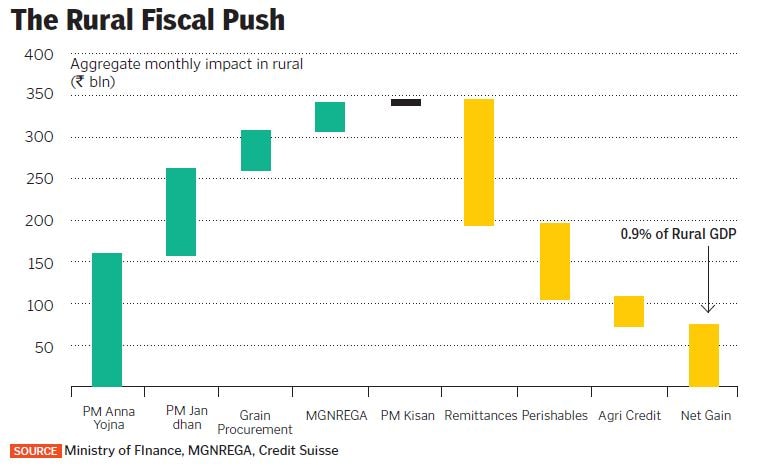

Chief among reasons for the bullishness on rural India is the fact that a large part of the government spending has been directed at rural India

Chief among reasons for the bullishness on rural India is the fact that a large part of the government spending has been directed at rural IndiaImage: STR /Nurphoto Via Getty Images

Rewind back a quarter and there was little or no talk of rural India powering India’s growth story. In fact, its economy faced considerable headwinds. Prices for agricultural crops had increased only modestly since 2014 and as real estate prices fell, the wealth effect was noticeably missing. Construction employment had dried up and manufacturing jobs found it hard to fill the gap. The net effect was depressed wages.

In its earnings calls, Hindustan Unilever, India’s largest consumer goods company with an extensive distribution network in India’s hinterland, spoke about how rural India’s sales, which were earlier growing at 1.5 times urban sales, had slowed to about the same pace as urban sales. It was finding it harder to sell ₹1 sachets of shampoo and ₹5 cakes of washing soap.

But the Covid-induced lockdowns and their devastating impact on the manufacturing and service economy have brought back focus to whether rural India can provide a modest cushion to growth numbers that are expected to contract between 5 percent and 12.5 percent this fiscal. Some initial signs have been encouraging. At 98,648 units in June, tractor sales were the highest this fiscal, according to the Tractor Manufacturers Association. But this was after a washout in April and May. It’s anybody’s guess whether these numbers will sustain. Biscuit manufacturer Britannia also reported a blowout performance, but again, it remains to be seen if this can sustain.

While there is reason to believe that agriculture will be the only growth engine this fiscal, it is also naïve to believe that its contribution will be anything more than an incremental 0.5 to 0.7 percent of growth. Agriculture makes up 29 percent of the rural economy, according to estimates by Credit Suisse. Allied activities like construction, manufacturing and financial services that make up as much as two-thirds of activity in rural India may or may not be able to pick up the slack.

As the virus enters its fifth month, the caseload from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal has been rising. The three states that accounted for a disproportionate share of migrants who had returned to their villages account for an average of 9,000 cases a day, prompting district administrations to impose local lockdowns. “While these lockdowns may not be strictly enforced, they do have an effect on manufacturing and supply chains,” says Neelkanth Mishra, co-head of equity strategy, Asia Pacific and India equity strategist at Credit Suisse. If activity is depressed, so are rural jobs and wages.

Fiscal Push and the Virus Spread

Chief among the reasons for the bullishness on rural India has been the fact that a large part of the government spending has been directed at rural India. While benefits for industry came in the form of a ₹500,000 crore fund for loan guarantees, money given to rural India has seen cash being transferred. The PM Anna Yojna, PM Jan Dhan, grain procurement, PM Kisan and MGNREGA are expected to add ₹350,000 crore to the economy.

A substantial part of this has been front-loaded. For instance, MGNREGA spends almost trebled to ₹12,500 crore in June when compared to April. PM Kisan payments were also advanced and in May, 81 million farmers received ₹16,300 crore as their first instalment, according to a government release. This year has also seen record procurement by the Food Corporation of India. Rice and wheat stocks moved up from 569 lakh metric tonnes in April to 832 lakh metric tonnes, pushing an estimated ₹100,000 crore to the rural economy. (Note: Figure includes procurement of jowar, bajra and other coarse millets.)

Some of these measures have resulted in a bump in everyday consumption items, but it is too early to call a trend. “The answer to whether this will sustain will be known around end-September or early October when the kharif crop is harvested,” says Sachchidanad Shukla, chief economist, Mahindra & Mahindra.

In its analyst call, Jyothy Laboratories, which has built a large rural network, said it saw a large part of its incremental demand for washing products and mosquito repellents coming from smaller cities and rural areas even as urban sales numbers stayed constant. The company saw profitability rise by 21 percent in the first quarter. But it was equally cautious of extrapolating this trend to the quarters ahead and refused to up its full year guidance.

Recent commentary on higher tractor sales and rising consumption of low-unit packs by rural consumers have resulted in optimists pointing out that the rural consumption engine is in fine fettle. They point to a plentiful rabi harvest with record procurement, low virus numbers and a disproportionate part of government relief measures directed at rural India. A key concern would be the fact that non-agricultural activities, which have been a bigger driver of rural growth coming unstuck. Mishra of Credit Suisse says the government’s spending as a percentage of GDP is among the lowest globally and the announcements so far do little to stimulate new demand. For now, the rural recovery or lack of it will be due to the virus. According to data compiled by Credit Suisse, the geographical spread of deaths is worsening and this could have a chilling effect on economic activity with agriculture and allied activities being hit. So far, the monsoon spread and sowing activity have not been affected, but increased caseloads during the harvest season could wreak havoc. Data shows that the number of districts with more than 500 cases as both a share of GDP and share of population has been rising steadily to over 60 percent. If one assumes that they follow the same time trajectory as their urban counterparts, their peaks could come around the time of the festive season. Expect a clearer answer then on growth prospects in India’s towns and villages.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)