Are personal loans growing too fast?

Leverage among ordinary Indians is doubling every three years and stands at $82 billion currently

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

In 2008, Ryan Marshall planned to buy a television set. What the Delhi-based salaried employee at a private sector company wasn’t prepared for was that he could walk out with one for ₹2 plus a series of payments staggered over the next year at no extra cost. “I was initially intrigued,” he says and “decided to try it out to see if the offer was indeed true.”

He didn’t know it then but Marshall had inadvertently stumbled upon the baby steps India’s financial services industry was taking in allowing Indians to leverage their personal balance sheets.

In the last decade, Marshall has used varying amounts of credit to purchase electronics, furniture, a refrigerator and an air conditioner. What attracts him is the simplicity of the process (no paperwork), its efficiency (disbursals take just a few minutes) and its convenience. The prudent user of credit that he is, Marshall says he always keeps his payments within ₹10,000 a month and always pays off one loan (usually over the course of 12 months) before starting another. He’s also got longer-term loans—a home loan and a car loan. Among his friends he’s noticed an increasing tendency to buy cellphones on credit, he says.

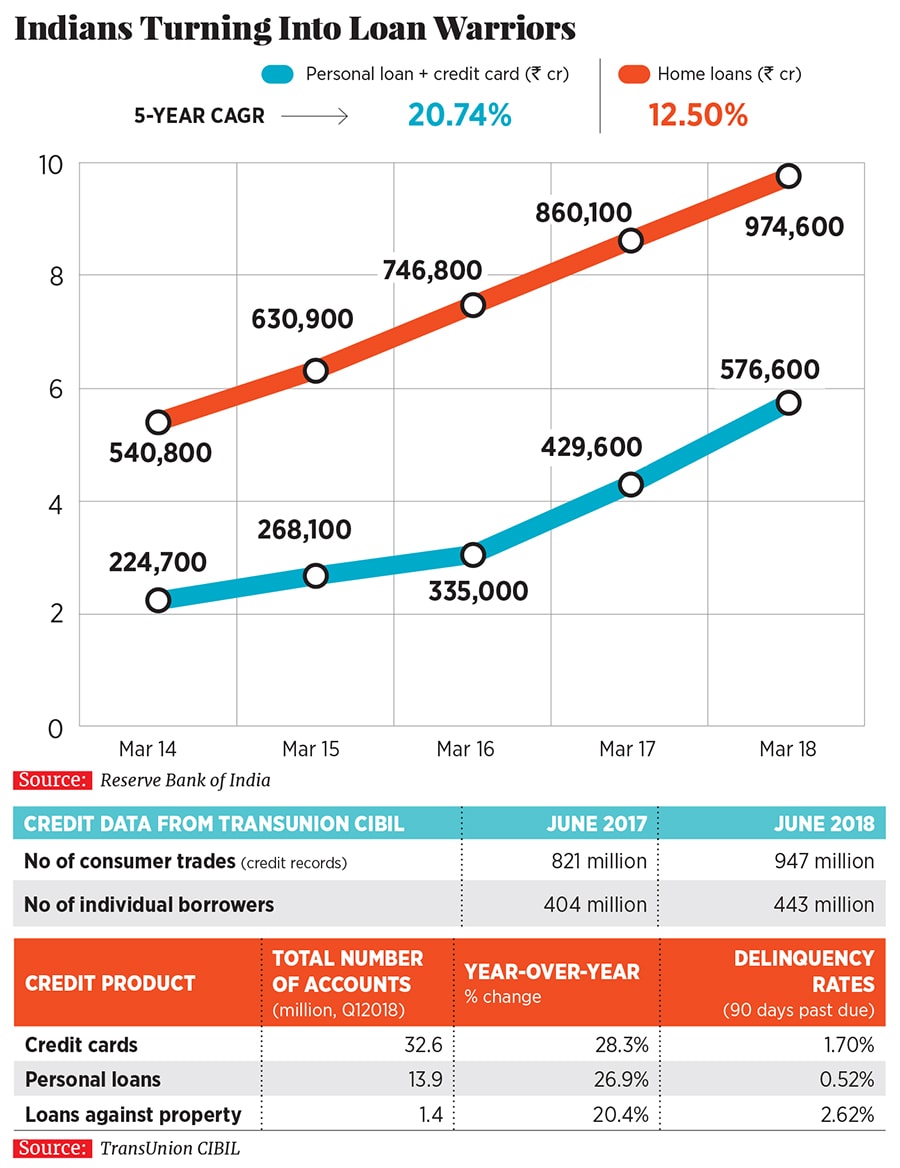

Marshall—and his friends—is clearly not an outlier. The numbers are staggering. Unsecured finance, which includes personal loans and credit card debt, amounted to ₹576,600 crore or $82 billion at the end of FY18, according to data from the Reserve Bank of India. To put that number in perspective, it’s almost double the inflows of foreign direct investment ($44.86 billion) in fiscal 2018. While a part of the $82 billion includes loans by small businessmen to finance the working capital needs of their business, the overwhelming majority goes into financing everyday consumption items.

If the decade till 2008 was defined by the rise of home loans and, to a lesser extent auto loans, the last decade has clearly been that of personal loans. Here loan sizes are much smaller, access easier and digitisation has resulted in lowering costs, which has increased penetration. “This can best be termed as a democratisation of credit,” says Deepak Mittal, co-head of credit business at Edelweiss, a financial services firm. Growing in excess of 20 percent a year it’s a pie that has the potential to surpass home mortgages that are growing at 12 percent. When compared to bank loans to industry and services, unsecured finance has grown four times that rate, according to a report by Crisil, a ratings agency.

Already one direct consequence of this shift has been a decline in savings rate from 31.25 percent to 29.98 percent in the last year. “Declining savings and rising consumer leverage could become a source of concern as so far the biggest source funding the India story has been the household,” says Dr Sachchidanand Shukla, chief economist at the Mahindra Group.

Last year saw household assets increase by 20 percent while liabilities shot up by 33 percent, pointing to worsening household finances. A slowdown in growth in consumer leverage typically elongates the recovery process. A recent study on household debt by economist Marco Lombardi at the Bank for International Settlements found that while in the short term consumer debt delivers a delta in growth, in the medium term it shaves off 0.1 percent growth.

For now the widening and deepening of the personal loan basket are poised to continue apace. It’s a shift that is likely to have profound implications in the way Indians accept, deal with and take on credit over the next decade. It also leads to the inevitable question of whether Indians could be setting themselves up for a credit trap as India’s banks were caught napping when credit card debt went south in the immediate aftermath of the Lehman crisis in 2008. Banks shrunk the number of credit cards in circulation as well as cut individual credit limits. (For now the default rates are manageable, according to data from TransUnion Cibil, which monitors consumer credit scores.)

Tapping them Young

Ground zero of India’s personal loan factory could be any mall or supermarket in urban—or even non-urban—India, like one of Future Retail’s Big Bazaars on a weekend evening. At one such shopping precinct in Matunga, Mumbai, representatives jostle to offer you credit cards and loan products that suit your needs. Future Group, India’s largest retailer, says credit has become a huge driver of growth and half of all electronics and furniture in its stores is sold this way. Through its tie-up with Bajaj Finance, its stores even allow customers to pay for groceries over 3 to 6 months.

A keen observer of shopping trends, Kishore Biyani, who founded Future Retail, believes he’s discovered the Holy Grail for the next stage of growth. An internal survey on customer aspirations showed that the number one product that young women desired was high-heeled sandals. “If your aspirations grow faster than your income, the only way to fund consumption is through credit,” Biyani had told Forbes India in a May 2018 interview. In all, the group sold a whopping ₹3,000 crore worth of goods on credit out of a total of ₹25,000 crore in fiscal 2018. This fiscal’s target for sales on credit is an aggressive ₹10,000 crore. Biyani declined to take a moral stand on the emergence of this trend.

The group is experimenting with various forms of credit and there is something for everyone. “Our data for the same consumer shows that when he (or she) has access to credit, they shop more,” says Vinay Bhatia, chief executive, loyalty and analytics, at Future Retail. There’s a plain vanilla credit card that it offers through a tie-up with the State Bank of India.

Bajaj Finance offers customers cards that work like credit cards but allows them to spread out payments over longer periods of three, six, nine or 12 months at little or no extra cost. Bajaj Finance now has 15 million cards in circulation across India and caters to customers like Sujith Kurup who has taken loans for four cellphones over the years as well as for a month-long backpacking trip to Europe. “It’s not like I don’t have cash, but when the need arose, I did not have cash,” grins Kurup, an employee with a recruitment firm in Vadodara.

Without credit scores, getting a quick loan was impossible. While Mehrotra stresses his product is not a payday loan, in practice at ₹9 a day for a loan of ₹10,000, the rates work out to 32.4 percent a year. Customers probably don’t feel the pinch as they pay off the loans quickly. Still, in an indication of how financially savvy they are, 25 percent apply for the loan after 11 pm so as to save a day’s interest. Earlysalary.com’s average loan is ₹15,000, average customer age 26 years and average loan tenure 22 days. Default rate is 1 percent. From ₹100 crore in loans Mehrotra expects to get to ₹400 crore by the end of the financial year and to ₹4,000 crore by March 2020. A large number of companies—Edelweiss, LendingClub, FlexiSalary among others—have entered the business lately.

Building Blocks

The bane of India’s lending industry had always been the difficulty in identifying users. Home loan verifications could often run into weeks and even then self-employed applicants were turned down as it became difficult to pin down their income details. Stories of a person having multiple PAN numbers are not uncommon.

All this began to change in 2012 when 250 million and counting Indians were enrolled in the Aadhaar database. Gone are the days of consumers filling lengthy forms and providing two photographs with every application. As of July 2018, 1.22 billion Indians have been enrolled in Aadhaar.

This data has allowed Bajaj Finance to “accelerate our business velocity, reduce documentation and reduce friction among our customers significantly”, says Rajeev Jain, managing director, Bajaj Finance. The company has been an early adopter of technology (Aadhaar numbers are verified within seconds through portable fingerprint machines) and has seen its consumer finance loan book grow from ₹13,360 crore to ₹39,161 crore in the last five years. Its stock has compounded at 94 percent a year in the same period.

As the problem of distinguishing Indians has been fixed, credit bureaus have been able to operate more effectively. “Our solutions have enabled real-time availability of consumer durable loans which consumers are increasingly preferring due to their ease of access,” says Harshala Chandorkar, chief operating officer at TransUnion Cibil.

TransUnion Cibil, India’s oldest credit bureau, now has data on 443 million Indians, up from about 4 million in 2004. It received 947 million inquiries for verifying the creditworthiness of loan applicants as of June 2018. Cibil also reports that 63 percent of Indians of the 440 million Indians it tracks have credit scores in excess of 700 (Cibil’s credit scores range between 300 and 900).

Lastly, there’s the low penetration of credit cards. With 39 million in circulation, India has among the lowest per capita credit card numbers in the world. The term often has a negative connotation in the minds of Indians. Marshall says he uses his two credit cards only for emergencies. In comparison, China has 588 million in circulation. Instead, Indians are increasingly warming up to monthly instalments as their preferred mode of credit. It gives customers a longer credit period often at no extra cost. The retailer and the manufacturer typically factor in this cost in their selling price.

The (Risky) Road Ahead

For now India’s retailers and financiers plan to keep the party powering ahead. It’s a path that Latin America trod a decade ago. “Historically retailers in Brazil have played a pioneering role in offering credit to lower income segments. At a time when credit was hard to find, retailers offered instalment payment plans through ‘carnes de loja’ (store booklets with details like payment dates and amount due)… lower income segments have traditionally been suspicious of banks and have found a warmer welcome at retailers for their credit needs,” according to a report by IESE Insight, a knowledge portal from the IESE Business School.

In the four years after 2008, consumer credit in Brazil rose by 25 percent a year. By 2013 a recession precipitated by falling prices of iron ore sent defaults soaring to 5.6 percent. Brazil’s middle-class dream became a debt-fuelled nightmare. In comparison, lenders insist that India’s default rates are manageable. “Things are unlikely to go out of hand unless you are lending to a concentrated set of customers either in a certain geographic area or occupation type,” says Rahul Prithiani, director-research, Crisil. There is also lesser risk of contagion as these loans are rarely securitised and resold.

As Brazil’s experience shows, consumers at the lower income strata are more vulnerable to income shocks. Retailers and analysts Forbes India spoke to agree that a large number of customers availing loans live from paycheck to paycheck. They declined to state this on record. This was also something the magazine confirmed in its observations at visits to retail stores. Several consumers worked as contract employees with a formal salary but little or no job security. (As an aside analysts point out that with credit to industry comatose, personal loans are the only game in town for India’s financial services companies.)

There also seemed to be a generational shift in their attitudes to credit. Few customers Forbes India spoke to thought of monthly payments of small amounts as a loan. Contrast that with Gopesh Shah, 44, who has been a customer of Bajaj Finance for his home and car loan. He says he is unlikely to take a personal loan for a depreciating asset. “If I was younger, I would probably take it as everyone around me is doing that,” says Shah, who works in PE-backed company in Pune.

If the experience of the last three years of affordable housing loans is a proxy, then consumer finance lenders would do well to provision for additional stress on their loan books. Home buyers that fit a pre-defined criteria get a ₹2.7 lakh subsidy per home. The data from this set is less than flattering. As against 1.96 percent defaults for all home loans, for loans below ₹10 lakh, the default ratio stood at 4 percent, according to a Crif High Mark, a credit bureau.

For now, the two biggest immediate risks to the industry are rising interest rates (G-Sec yields are at 7.9 percent) and a decline in underwriting standards as more and more competition floods the sector. Already there are indications of some non-banking finance companies offering loans to customers with credit scores of 650 and below. If growth slows on account of a trade war, or rising oil prices or a run on the rupee, these loans could be a lot harder to recover.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)