Big story: The Chinese dragon's grip on imports

Indian industry will need time and support from the government to reduce its reliance on Chinese imports

Image: Shutterstock

Image: ShutterstockVoltas’ air conditioners are assembled in India. In the eyes of Indian consumers, they are a made-in-India brand.

But look under the hood of the air conditioners and 50 percent of components—compressors, controllers, motors and copper tubes—come from China. “There is no Indian compressor manufacturer,” says Pradeep Bakshi, managing director at Voltas.

While the company is looking to develop a vendor ecosystem, it would take a minimum of 12-18 months to put that in place. Bakshi says the company is exploring several options, including tying up with rivals, to set up a compressor facility that can manufacture at scale. Vendors in this space work on large top lines and low margins and no one Indian air conditioning company can give them the business they need to be viable.

In the interim, Voltas continues to import from its Chinese suppliers. The recent border skirmishes as well as the government’s call for industry to become ‘aatmanirbhar’, or self-reliant, have done nothing to halt their Chinese imports. It’s business as usual.

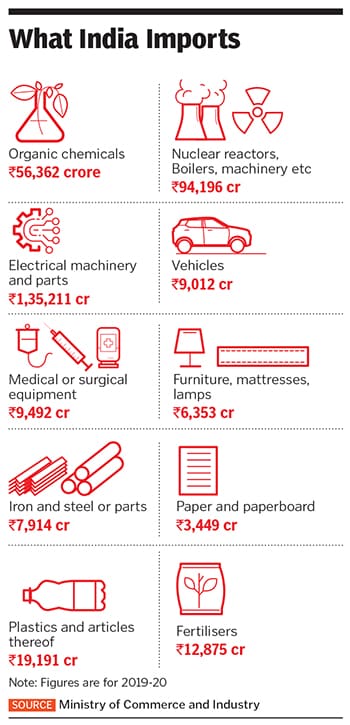

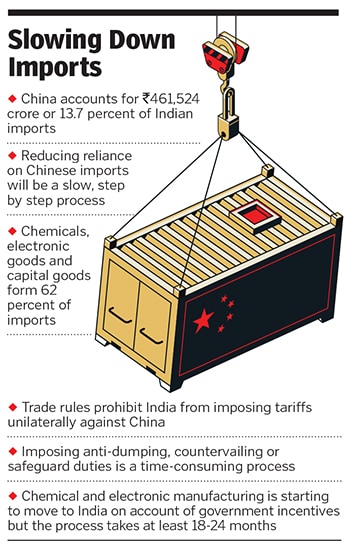

For India, imports from China stood at ₹461, 524 crore ($61.5 billion) in 2019-20, according to the ministry of commerce. Three sectors—organic chemicals, capital goods and electrical items (television tubes, mobile phone parts and compressors, among others) —account for 62 percent of these imports. While economies of scale are not a problem in several businesses like mobile phones, Indian industry continues to import from China. “This situation has come because of our complacency in blindly accepting cheaper imports from China,” said Sajjan Jindal, chairman of JSW Group, in a statement. The JSW Group’s annual imports from China total $400 million (₹3,000 crore).

While companies move to shift manufacturing to India, an additional wrinkle is that since India is a signatory to the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, it cannot unilaterally hike tariffs against any one country. Vendors setting up plants in India could still be swamped with imports from, say, Vietnam or other WTO members.

“The only way out is to provide support for both domestic and overseas manufacturers who want to set up operation in India,” says Jayant Dasgupta, India’s former ambassador to the WTO. At least one industry executive who declined to be named said his business was adopting a wait and watch attitude and would continue to import from overseas.

Industry Takes the Lead

One area where Indian industry has had success in reducing dependence on China has been in the organic chemical space. These comprise chemical compounds that act as raw materials to a host of industries—active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for the pharma industry are a prime example.

The industry has seen several success stories with manufacturing shifting out of China primarily on account of environmental concerns. But even here, there are instances of raw materials coming from China. “Things flow from the petrochemical value chain and the starting blocks are bulk commodity chemicals that need to be made at humongous scale for the economic viability to set in,” says Koushik Bhattacharya, director and head industrials at Avendus Capital, an investment bank.

So, on the bulk chemical side, there is limited scope to set up operations in India and raw materials are sourced from China. India only makes ethylene and propylene and most of that feedstock is used for the manufacture of polymers. While backward integration is possible, there is a limit to how much Indian businesses can invest and Bhattacharya reckons that investments are only possible by companies that are valued at over $1 billion (₹7,500 crore), of which there are only a handful.

“Any move to reduce dependence on China for raw materials would force companies to import from Europe and increase costs,” says Vinati Saraf Mutreja, managing director & CEO, Vinati Organics, one of the leading companies in the chemicals space. The company exports its finished products to China and any tariff retaliation by China would have a negative impact on its business. The company has seen its market cap compound at 30.4 percent a year in the last five years to ₹10,500 crore.

Another area that has been steadily gaining ground is contract manufacturing. As India’s domestic market grows, original equipment manufacturers are making more televisions, washing machines and mobile phones in India. “Component manufacturers go where the demand is,” says Sunil Vanchani, chairman of Dixon Technologies, a Noida-based contract manufacturer. His company manufacturers home appliances, lighting solutions and mobile phones and says enquiries for more contract manufacturing have come in the last few months but land acquisition has proved to be a hurdle.

According to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, electronics manufacturing has grown at a CAGR of 25 percent in India for the last four years and domestic hardware worth $70 billion (₹300,000 crore) is made in India. Key to getting more companies to shift base to India is financial support from the government to provide incentives to set up manufacturing facilities. In April, the Production Linked Incentive Scheme for Large Scale Electronic Manufacturing announced ₹40,951 crore of incentives over the next five years based on certain investment milestones. Expect more companies to announce plans to set up electronic- and semi conductor-making facilities in the next few months.

Last, there is capital goods—a sector that has been in the doldrums for the last decade. Demand for setting up new power plants, mining and construction equipment, and boilers and turbines has been flat or declined sharply over the last five years. In the interim, supplies from China have risen from ₹69,000 crore in 2015-16 to ₹93,000 crore in 2019-20 while Indian manufacturers have struggled to match Chinese prices. For now, the government has not announced any incentives to move capital goods manufacturing to India.

Trade Terms

An additional challenge in moving manufacturing to India is the level of support the government can provide to industries. The WTO prohibits the use of unfair incentives and countries are allowed to impose anti-dumping duties, countervailing duties and safeguard duties to level the playing field. China’s manufacturing journey started before it joined the WTO in 2001 and a large amount of investments had already been made at favourable terms to manufacturers. That is an advantage not available to India.

Recent reports of Chinese containers being scrutinised at Indian ports have not been backed by written notifications, according to trade lawyers. Dasgupta who represented India at the WTO finds the import restriction debate ill-informed and ill-advised. “When we harass importers we only end up hurting our interests,” he says. Instead, the government needs to work step-by-step to identify sectors that we need to reduce dependence on and then work on getting those manufacturers to set up shop in India.

The experience of India’s textile industry provides a sobering example of what can go wrong. Since the abolition of US and EU textile quotas in 2004, the gains have flowed disproportionately to China, Bangladesh and Vietnam. India has only managed to carve a niche in home textiles—a smaller and less lucrative part of the market. Indian textile makers have long complained of high electricity charges, inflexible labour laws and the stuck GST refunds.

For now, as Voltas’ troubles in sourcing compressors in India show, the road ahead in getting companies to manufacture in India is long and arduous. What India has going for itself is the China Plus One strategy—which involves diversifying investments into other countries to reduce overconcentration in China—that western companies are actively pursuing. Still, it is far from certain that India would be the only beneficiary and countries like Vietnam, Thailand and Bangladesh could end up benefitting more. Imports from China would then shift to these countries.

Expect plenty of posturing like the recent rules that mandate ecommerce companies display the country of origin on their products from August 1. As Mekhla Anand, partner (indirect tax), at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas says “The government has not issued any notification restricting the import of goods from China. While delays are being reported in clearance of shipments, these appear to be procedural issues.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)