ISRO's Dead End in Space

Just like some of its rockets, India's space agency is losing direction. By being more open, it can begin to stop the slide

April is the cruellest month,” wrote T.S. Eliot in The Waste Land, a poem noted for its rich metaphors and allusions that describe a soul’s struggle in the post World War I moral decay. In the next few weeks, India’s space agency will experience that firsthand as the unforgiving gaze of public scrutiny turns towards it. Two high-stake launches — that of a polar orbiting rocket and a communication satellite — are scheduled for this month and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) cannot afford to go wrong with them. The unqualified admiration it elicited from the public for its success with the moon mission in 2009 seems like a distant memory now. A year of glitches in satellites and rockets rounded off with allegations of a scam has put ISRO under immense pressure and its credibility is in question like never before.

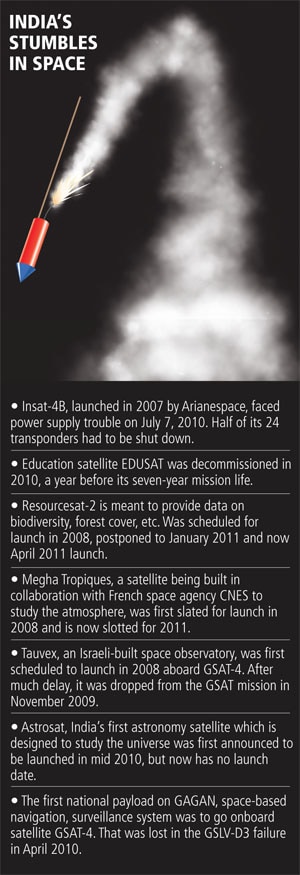

If nothing else, ISRO has been guilty in recent years of letting its public image deteriorate steadily and of doing nothing to arrest the slide by encouraging an open debate about its functioning. The situation spun out of control when a series of mishaps hit and the public turned sceptical about the space agency. The failure of the indigenously developed cryogenic engine in April 2010 and then the crash of the launch vehicle GSLV-F06 in December were bad enough, but the nation soon came in for another nasty surprise: The ISRO-Devas Multimedia deal for broadband spectrum that politicians and media described as a scam bigger than the 2G corruption scandal.

The opinion in the scientific community is more nuanced but no less critical. They see a huge public organisation that is losing its research edge and slipping into a bureaucracy; a place where communication has broken down with the external world as well as within. They say ISRO is still full of honest people and that the Devas deal was not a scam at all; but they also say the organisation is straying from its core ideals. ISRO officials did not agree to be interviewed and failed to answer a detailed questionnaire from Forbes India on these issues.

ISRO can hardly afford to get mired in organisational hiccups when the space race is heating up. China has made rapid strides in the last five years, putting a man in space. Advanced nations are moving in to colonise space and use it for their strategic advantage. For India to remain in this game, ISRO must buckle up and perform quickly.

More specifically, a whole lot of important missions will suffer if ISRO delays launching a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) with an indigenously developed cryogenic engine. At stake is not just the future of two big announced missions — Chandrayaan-2 in 2013 and the manned flight to the moon in 2015 — but significant commercial opportunities to sell its services to the rest of the world.

The satellite launch market is seeing a boom with geostationary satellites getting bigger and more complex to meet the burgeoning communication needs of a connected world. Paris-based consulting firm Euroconsult expects this trend to continue till 2018. India must rush to exploit this opportunity before the window closes. India and China are the two forces that can challenge the market leader, Russia. But poor reliability of GSLV will not only dent ISRO’s commercial prospects but even its image, which is directly related to India’s prestige.

Up, Up and Ouch

Failure is hardly a bad thing. Or uncommon in the world of space research. The fact that India’s space agency is seeing more failures now “shows that ISRO has reached a certain level of maturity which certainly calls for modern governance,” says Steve Bochinger, president of Euroconsult North America. Other space agencies have similarly struggled with launch failures, organisational bottlenecks or confusion about long-term vision that ISRO is experiencing right now.

But then, a culture of openness, leadership and a high standard of accountability are the prescription for cure. And sadly ISRO ranks low in those departments.

Take the case of the crash of GSLV-F06 (with an imported cryogenic engine) in December 2010. A Failure Analysis Committee was formed to look into it but experts associated with the exercise say they are not aware if it “is completed and a cohesive report prepared”. The Committee chairman, former ISRO boss G. Madhavan Nair, had given varying explanations as the work was in progress and a final report would have cleared the air.

There is a larger review under way and its findings are disturbing. The GSLV Review Committee, led by another former ISRO chief K. Kasturirangan, says there is “no pattern to failures,” and points to a lack of rigour and attention to details.

This had not been the case before. When earlier launch systems such as ASLV failed, scientists knew what they didn’t know.

The case of the locally made cryogenic engine is more puzzling. To understand and pinpoint the error in the April 2010 experiment, ISRO must adopt a complete mathematical model to simulate the cryogenic system through which it could test the engine under varied, even hypothetical, conditions. For instane, if the booster pump hadn’t worked properly because it was submerged in liquid hydrogen, the test would have revealed it. But ISRO hasn’t done such a test. “Along with empirical understanding [from experiments], you need to have physical understanding [from simulation],” says B.N. Raghunandan, professor of aerospace engineering at Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

The mishandling of situations didn’t stop with technical issues. When news broke in February suggesting that ISRO’s marketing arm, Antrix Corporation, had entered into a deal with Devas Multimedia in 2005 to favour the latter, the space agency dithered and failed to explain the true picture to the public.

All that Antrix had done was to resort to “procedural” shortcuts in getting the deal approved by its board. It was done at a thinly attended meeting. Experts close to ISRO say if it had just continued with the traditional INSAT Coordination Committee meetings (it was last convened in 2005), which routinely involved all key science, technology and telecom departments, things wouldn’t have come to this flashpoint.

But popular belief held that the deal that involved using Devas’ technology to provide satellite broadband services was the mother of all scams. The whole country was then in a mood to see a scandal in everything.

No Space for a Chat

Of all the problems at ISRO, insiders say, the lack of communication among its own arms is the most troubling. “They really have a management issue. There are so many good people working for them but they don’t seem to communicate with each other,” says Jayant Murthy, a professor at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics in Bangalore, who worked with ISRO for three years on an aborted project. Murthy was the principal investigator for Tauvex, a joint space observatory project between Israel and India. After a four-year delay, it was finally mounted on the satellite in November 2009, but got knocked off at the last minute when ISRO realised the weight of sundry payloads on the mission exceeded the limit. Despite repeated requests, ISRO never communicated the next launch date. Tauvex was finally sent back to Israel last year.

“It’s a result of constantly changing set of priorities at ISRO, which now works in mission mode,” says Murthy, who along with his Israeli counterparts, is contemplating a Russian launch. The new thrust on commercial success may have come at a time when the focus on research is diminishing, say experts. “Instead of doing research, ISRO scientists are becoming large-scale managers,” says Raghunandan of IISc.

Kasturirangan suggests a model of concentric rings: At the core is the application-driven vision that Vikram Sarabhai, the father of Indian space programme, laid down; around that ISRO needs to build programmes like Chandrayaan where bilateral and multilateral co-operation can add value; and the third ring should be even larger space programmes like a manned Moon mission. “There’s no end to the space programme for the next 100 years; we need to have a vision,” he says.

This vision, to start with, was developing applications for the society’s benefit such as weather forecasting and enabling communication. But there are questions on ISRO’s committment to it.

“I feel concerned about the relative shift in focus that ISRO has emphasised — from being application-driven to technology- and prestige-driven,” says Kiran Karnik, former president of software lobby Nasscom and who had worked at ISRO for two decades. Karnik, who recently resigned from the board of Devas, recalls how a large group of 150 social scientists constituted the ‘conscience’ of ISRO and helped it define national priorities. That mechanism exists no more.

In the interplay between political leadership and scientific vision, the former is proving dominant. “Somebody should argue back and talk about the real issues that India’s space programme faces,” says Karnik.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)